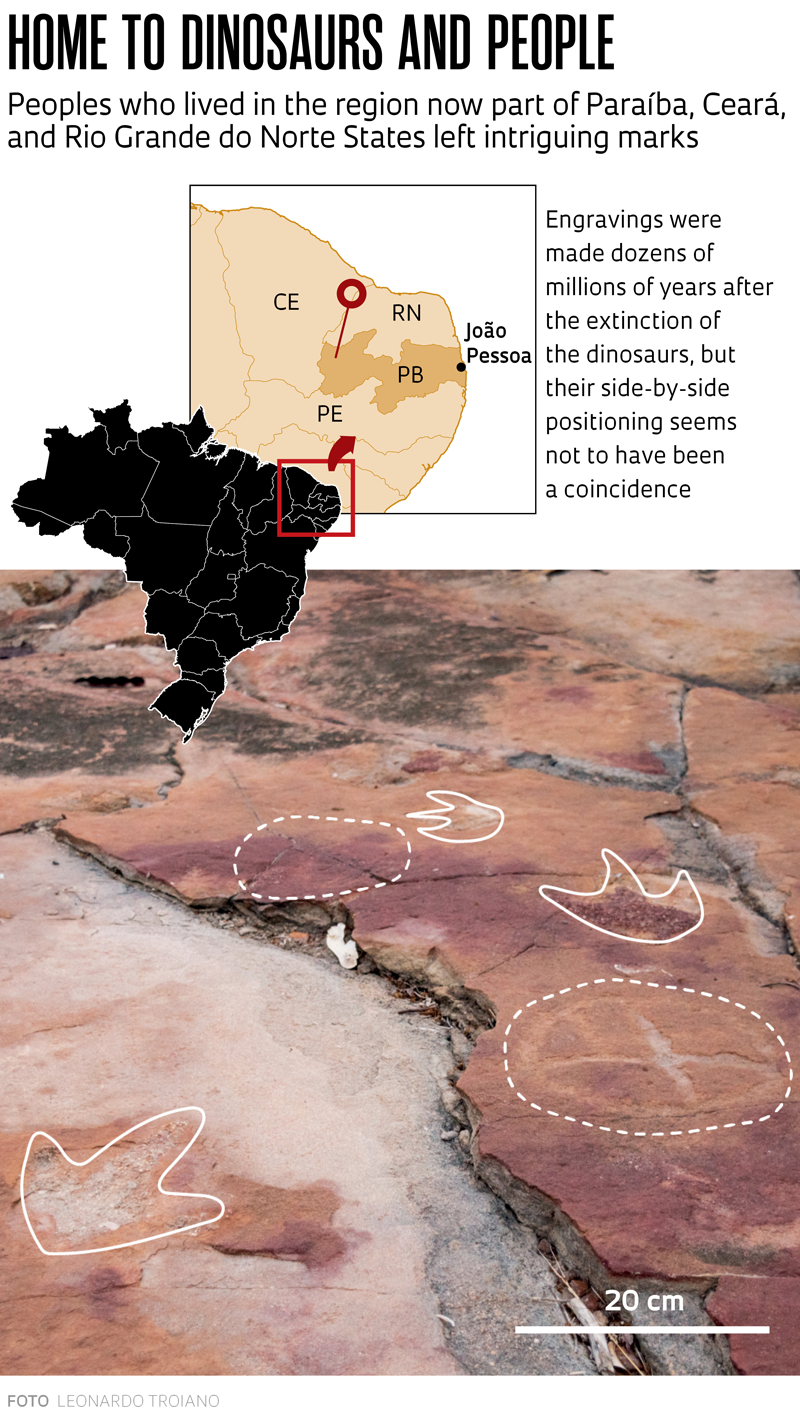

In the Paraíba State backland municipality of Sousa, dinosaurs are something of an attraction; abounding in preserved footprints, the Valley of the Dinosaurs conservation unit is open to visitation, and also home to a museum of fossils found in the area. Consequently, paleontologists were the most interested in the region until recently. The attraction now is for archaeologists: at the Serrote do Letreiro site, 11 kilometers (km) from the town, there is also rock art on the ground made by people who may have lived there up to 9,000 years ago, associated to the footprints left by animals between 130 million and 145 million years ago. These primitive messages, never before seen in Brazil, suggest that the parallels were intentional, according to an article published in the journal Scientific Reports in March.

“This site is a real overdose of information,” says paleontologist Tito Aureliano, one of the study authors, a postdoctoral researcher at the Regional University of Cariri (URCA), and one of the coordinators of the Diversity, Ichnology, and Osteohistology Laboratory (DINOLAB) at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). “There is a considerable temporal mix there: rocks almost 1 billion years old, then you walk 50 steps and see traces of the Cretaceous Period (about 130 million years ago); there are dozens of different dinosaur footprints and human engravings made some thousands of years ago,” he adds.

Serrote do Letreiro is an area of 15,000 square meters (m2) in the Paraíba sertão (badlands) on a private property. The site was first recorded in the late 1970s by Italian paleontologist Giuseppe Leonardi, one-time professor at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) and the State University of Ponta Grossa (UEPG), now retired. At the time, he classified the markings — or petroglyphs — as “Cariri Indigenous carvings,” and focused his interest exclusively on the dinosaur prints. “These human engravings attracted no attention,” remarks paleontologist Aline Ghilardi, of UFRN, also coordinator of Dinolab and coauthor of the recent study.

Renan ChanduThe researchers examined the markings and mapped the site by drone during an expedition to Serrote do LetreiroRenan Chandu

“It has always intrigued me that there were never any answers about what those human markings were, so I decided to recruit some help,” says the dinosaur specialist, a regular visitor to Serrote do Letreiro for almost a decade; in 2023 she invited archaeologist Leonardo Troiano, of the Brazilian National Institute for Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN), to visit the site. Troiano flew from São Paulo to Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará State, and then took a 190-km bus ride to Sousa, with a further leg on a hard dirt road to the site. Towards the end of the journey, he ripped his pants on a barbed-wire fence.

The long, eventful trip was, however, rewarded. “At day’s end, before a magnificent sunset, the shadows of the last 15 minutes of waning sunlight bring out the footprints and engravings; it’s amazing,” enthuses the archaeologist. During the visit, the group commissioned drone pilot Arthur Sampaio to produce high-resolution images — the intention of the article researchers is to build a 3D digital model of the site. The etchings take the form of tridigits, grids, and circles with patterns of crossed lines, like stars.

According to the researchers’ interpretations, some of the inscriptions imitate three-toed feet. The petrified footprints enabled identification of three different dinosaur types: theropods, sauropods, and ornithopods. Archaeologists describe the human groups that lived there as semisedentary peoples who camped, foraging and hunting for what they needed before moving on to the next location.

Similar markings have been seen in parts of northeastern Brazilian states Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará close to Sousa, indicating that those civilizations inhabited all of the surrounding area. What sets the markings found in Serrote do Letreiro apart from the others is that the etchings there were made in the ground. “It’s curious, because normally engravings associated to that culture are found on vertical or inclined rock panels, so there is strong evidence that this ancient population made their rock art there because of the footprints; there is a direct association between the markings,” infers Ghilardi.

Archaeologist Valdeci dos Santos Júnior, from Archaeology Laboratory O Homem Potiguar (The Potiguar Man—pertinent to the region of Rio Grande do Norte State) (LAHP), of Rio Grande do Norte State University (UERN), who did not participate in the study but authored the book A pré-história do Rio Grande do Norte (Prehistoric Rio Grande do Norte), believes that the hypothesis in Scientific Reports is worthy of attention. “It’s possible that the ancient engravers respected the space of the footprints, because the petroglyphs do not overwrite them,” he says. For the first time, says Santos Júnior, a study reveals evidence of a site that was inhabited both by dinosaurs and human groups. “The two groups did not coexist; they are from two different periods,” he stresses, going on to state that there is a need to find other sites with the same characteristics to identify a pattern and reinforce the hypothesis that human beings liked to reproduce dinosaur footprints. “It is not so simple a question—tridigits are common engravings in the Northeast, and can represent birds, other animals’ footprints, or even plants such as cacti, a common part of the landscape.”

That having been said, other reports point to interactions between people and dinosaur prints in Australia, Poland, and the US. In Brazil, the association is unprecedented, although the relationship with fossils has been frequent over the course of history. In southern state Rio Grande do Sul, Troiano affirms, some constructions, such as older churches, were built using fossil timber, which looks different from common wood. Legends and stories from Ancient Greece were inspired by the discovery of fossils, according to the archaeologist. The bones of mammoths and other giant animals would be portrayed as heroes in these stories. “The site in Pelopponessus, where they believed the Gods and Titans to have clashed, is a fossil deposit,” reports the researcher.

For the specialists, finding human records beside footprints suggests that ancient Brazilian communities also valued discoveries of the past. “These peoples inhabited the Americas for 50,000 years in deep harmony with the natural world, and such discoveries most certainly had a special value for them; it was not something trivial,” says Santos Júnior.

Understanding of dinosaurs only emerged in the nineteenth century, with the publication of On the Origin of Species by British naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882), and popularization of the theory of evolution. “Until that time, people just didn’t think about large extinct animals,” says Santos Júnior. These symbolic records are the vestiges of groups that predated the arrival of the colonizers in Brazil. Other research should seek out more signs to sustain this possible connection between dinosaur footprints and petroglyphs.”

Scientific article

TROIANO, L. P. et al. A remarkable assemblage of petroglyphs and dinosaur footprints in Northeast Brazil. Scientific Reports. Online. mar. 19, 2024.