Avariant of the Oropouche (Orov) virus, which causes Oropouche fever, identified in January in the northern region of Brazil, may be responsible for the current spread of the disease throughout the country. As of August 19th, the Brazilian Ministry of Health registered 7,653 cases (the figure for 2023 was 831), including four cases of microcephaly and the death of two women, 21 and 24 years of age, neither of whom had any underlying conditions, with symptoms similar to those of dengue. These deaths were the first recorded globally due to this virus variant. On August 3rd, the Health Ministry confirmed the first fetal fatality from the virus, which was transmitted from mother to son in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. Up to the 5th day of the same month, São Paulo State had confirmed five cases.

A study at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), published in July on the medRxiv platform, illustrated that the variant known as Orov_BR-2015-2024, or new Orov, when inoculated in human cells, produces 100 times more virus in a 48-hour period than the first strain isolated in Brazil in the 1960s. When cultivated, this new variant formed pits in the cell layer that were up to 2.5 times larger than those formed by the previous strain.

“New Orov is capable of replicating more quickly and evading some of the antibodies produced by the immune system in response to previous infections,” observed virologist José Luiz Módena, coordinator of the UNICAMP team. “As it is very quick to multiply, it can likely reach higher quantities in the blood of infected people or animals, potentially favoring infection of the transmitting insect.” The main transmitter currently is the maruim or paraensis midge (Culicoides paraensis), the larvae of which feed on organic material found in forests, parks, and plantations, usually on the outskirts of cities.

Módena and his team examined blood samples from residents of Manaus, Amazonas, collected in 2024. Among the 93 samples, 10 were from people with Oropouche fever. Two were sequenced and identified as new Orov, first described in January by the virologist Felipe Naveca of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) Amazônia in Manaus.

Scott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research Service Maruim, transmitter of OropoucheScott Bauer, USDA Agricultural Research Service

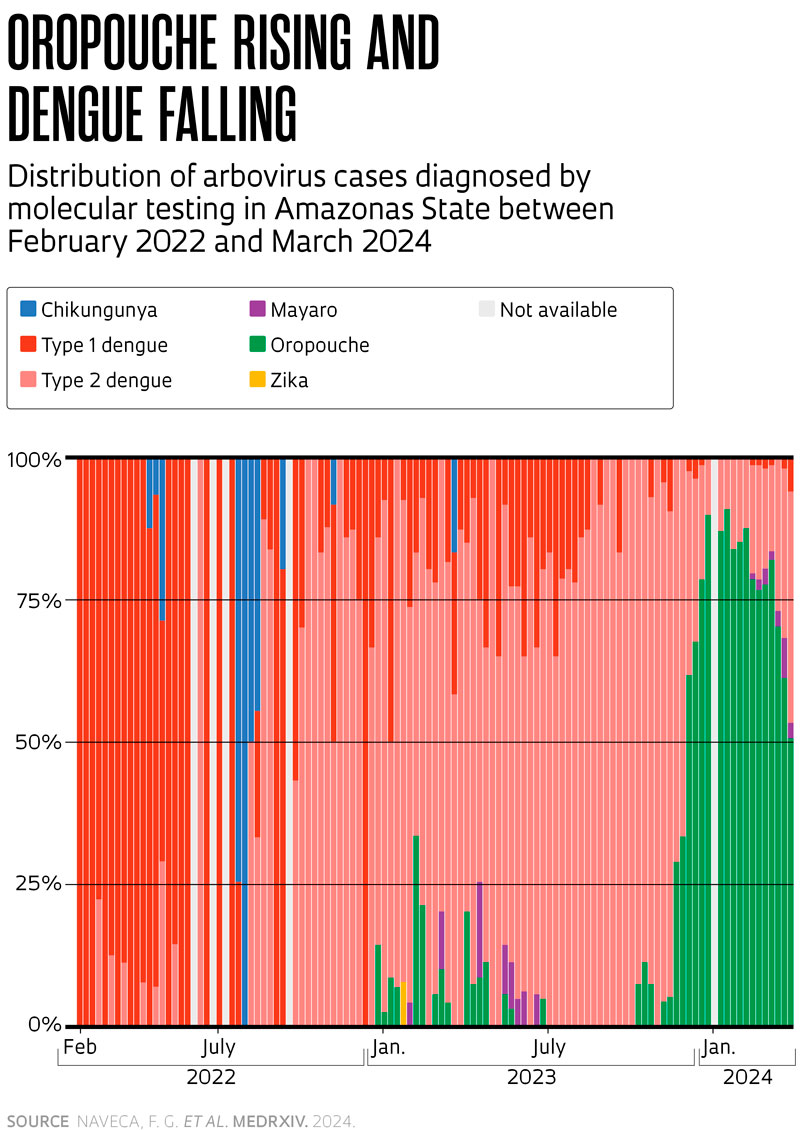

The new strain was identified after sequencing 400 viruses collected during the outbreak in the Amazonian states of Rondônia, Roraima, and Acre between 2022 and 2024, as detailed in a preprint published by Naveca on medRxiv on July 24. “New Orov emerged between 2010 and 2014 after genetic rearrangement of three different viruses that circulated in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia,” says Naveca.

“This is a virus with a high capacity for killing the cells it infects,” says virologist Eurico Arruda, of the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine (FMRP-USP), where studies into Oropouche began in the 1990s. As Arruda detailed in a 2017 article in the Journal of Medical Virology, the virus infects leucocytes—immune system blood cells—through which it spreads throughout the organism. In a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Neuroscience, Arruda’s team and that of Adriano Sebollela, also of USP at Ribeirão Preto, demonstrated that Orov can multiply in sections of the human brain, causing an inflammatory response harmful to the organism.

Researchers interviewed by Pesquisa FAPESP agree that the new variant is not the only factor driving the Oropouche fever epidemic. Rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns due to climate change may have widened the maruim vector occurrence area. Moreover, deforestation in Amazonia may have driven insects into urban areas.

The intensification of diagnostic testing by the national network of the Central Public Health Laboratories (LACENS) has also contributed to an increase in the number of recorded cases. Severe cases were diagnosed with the test developed by the FIOCRUZ Amazonia team, distributed to other countries through the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

“We started paying more attention to Oropouche when we found that a large proportion of outbreaks were not due to dengue, an illness with which it is easily confused,” states infectologist Julio Croda, of the Campo Grande FIOCRUZ regional office. He believes that the high numbers and geographical distribution of cases, with confirmed reports across 20 of the 27 Brazilian states, constitute an Oropouche fever epidemic in Brazil (see map). “This situation is very different from local outbreaks that occurred in North Brazil up to last year,” he comments.