Less than 13% of Brazilian municipalities have strong institutional capacity and a reasonable number of legal instruments to help them adapt to the impacts of climate change. Generally wealthier, cities with populations above 500,000 inhabitants tend to have more data and initiatives that can serve as a foundation, or prerequisites, for the formulation of adaptive public policies than smaller cities with up to 50,000 residents. These are some of the findings of a study published in July in the scientific journal Sustainable Cities and Society.

The study analyzed 25 indicators reflecting conditions in the 5,569 municipalities that existed in Brazil in 2021 and, based on this data, calculated a General Urban Adaptation Index (UAI). “The index measures institutional capacity, the adaptive potential a municipality has in the face of climate change,” explains Gabriela Marques Di Giulio, from the School of Public Health at the University of São Paulo (FSP-USP), coordinator of the study. “This potential is the starting point for cities to develop public policies focused on adaptation.”

The indicators that make up the UAI cover five areas: housing, urban mobility, local food production, environmental management, and climate risk management. The first four reflect general adaptive capacity, while the last addresses the specific ability to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change. In addition to allowing for the calculation of the UAI, the approach also makes it possible to produce specific indices for each of the five areas.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESPThe city of São Paulo, marked by deep social inequalities, achieved a solid score of 0.89 on the UAI adaptation indexLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

The UAI score (and the specific indices) ranges from 0, the lowest level, to 1, the highest. The same methodology was used in a previous study by the group, published in 2021 in the journal Climatic Change, which analyzed all 645 municipalities in the state of São Paulo. All the information used to calculate the UAI is publicly available and was drawn from the 2020–2021 edition of the Basic Municipal Information Survey (MUNIC) by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). The new study received financial support from FAPESP, the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), and the Federal District Research Support Foundation (FAPDF).

According to the UAI, the adaptive capacity of municipalities varies widely. “We expected the index to show clearer differences between municipalities in wealthier regions of the country, such as the South and Southeast, and those in areas with lower HDI [Human Development Index], such as the North and Northeast, but we didn’t find strong evidence of regional disparities,” comments climatologist Roger Rodrigues Torres, from the Federal University of Itajubá (UNIFEI) in Minas Gerais, coauthor of the article.

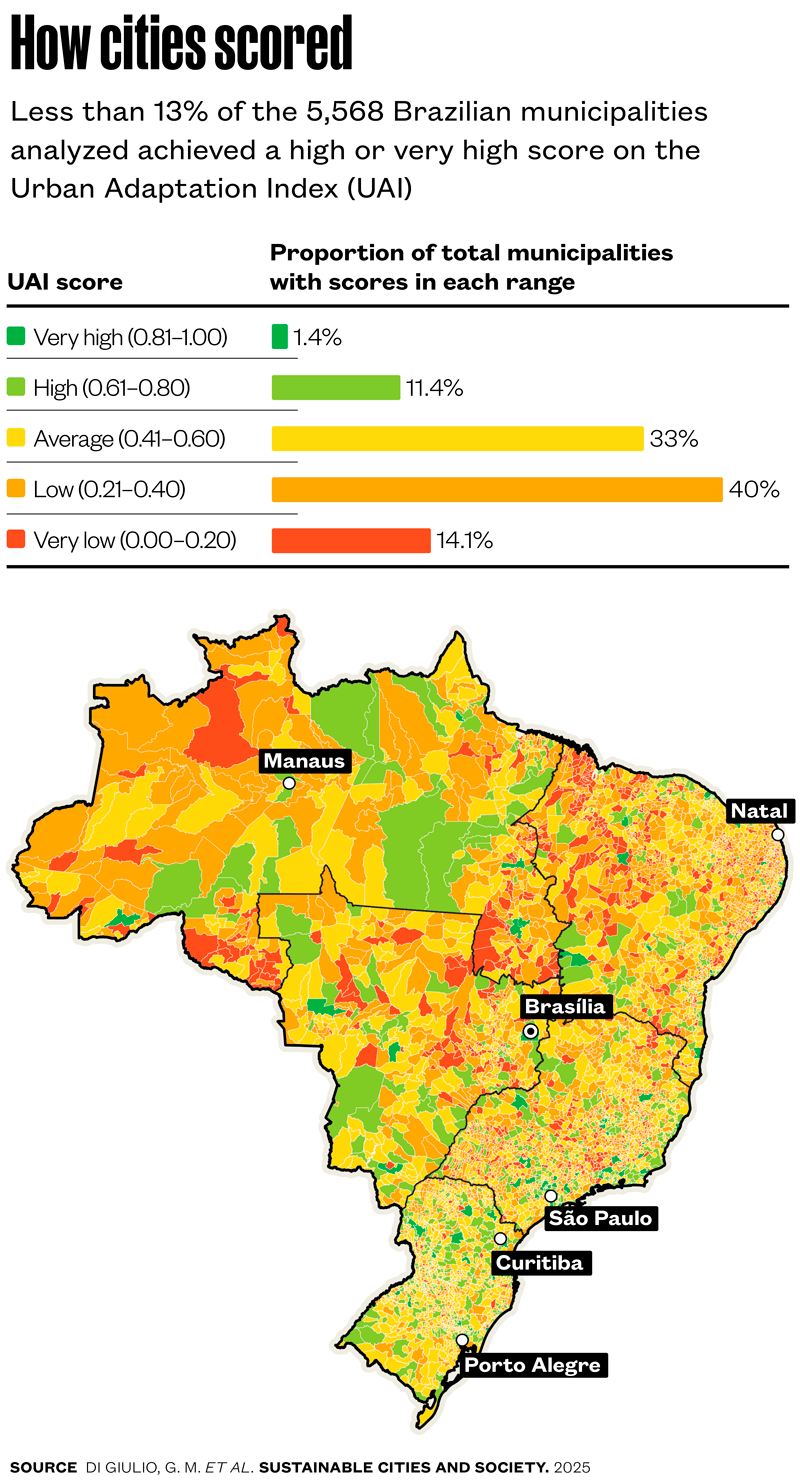

Only 1.4% of cities scored above 0.81, within the highest range, and 11.4% achieved performance considered between reasonable and good, with a UAI between 0.61 and 0.8. In the remaining municipalities, the index was below 0.6, and more than half received low or very low scores. The average UAI for Brazil’s 49 most populous municipalities, each with more than half a million inhabitants, was 0.74. In 4,893 small cities with fewer than 50,000 residents, the index ranged from 0.33 to 0.44, a poor result. Among the capitals, the final UAI scores varied widely. The highest-scoring cities included Curitiba (0.98), Brasília (0.95), and São Paulo (0.89). The lowest—Recife (0.46), Boa Vista (0.54), and Aracaju (0.54)—failed to reach 0.6.

If the UAI values are not encouraging for most municipalities, the situation is even worse when considering only the indicators that measure the existence (or absence) of policies specifically aimed at managing climate risks. These basic parameters assess whether a city has its own civil defense structure; land use and zoning laws related to flood and landslide prevention; a geotechnical map to guide urban planning; and a local plan to identify geological and physical risks and define interventions or investments to minimize their impacts.

Only 4.9% of the more than 5,000 municipalities scored above 0.6 on the specific climate risk management index, while 65% scored below 0.2 (see map below). “Only 13% of cities reported having municipal risk reduction plans in 2020, and just 5.5% had geotechnical maps,” says Di Giulio. “These data are very concerning.”

A high UAI score does not necessarily mean a municipality is well adapted to climate change. It simply indicates that the city has data and mechanisms, such as land use and zoning laws, or environmental and climate risk management plans, that could be used in the adaptation process. In other words, the municipality has built adaptive potential but does not necessarily use it. Researchers have not yet found a reliable way to measure whether cities are effectively using this potential. One possibility is to follow the money: gather data from municipalities on the allocation of funds specifically intended to combat and mitigate the effects of climate change and related disasters. The challenge is that collecting this information for all municipalities in Brazil is no simple task.

Climate justice

In the recently published study, the researchers selected two capitals that scored highly on the UAI, São Paulo and Brasília, and analyzed their situations in greater detail. The goal was to determine whether these high scores actually reflected well-implemented public policies for climate adaptation. “According to the adaptive capacity indicators we surveyed, these two cities would have all the necessary ingredients to bake a cake and adapt—but they don’t,” comments biologist Diego Lindoso, from the Center for Sustainable Development at the University of Brasília (CDS-UnB). “Not all adaptation actions are carried out by governments, but their role is essential to ensure that public policies aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change benefit everyone, especially the most vulnerable populations.”

According to the article, public policies intended to mitigate the effects of climate change have had little impact on the poorest neighborhoods of São Paulo and the administrative regions of Brasília. The most deprived areas of both cities have fewer green spaces (which help soften the impacts of extreme weather) and contain the highest concentrations of hydrogeological risk points, as well as the most frequent landslides and floods. The extreme contrast between rich and poor urban areas can be seen, for example, in the two Brasília landscapes shown at the beginning of this article: Lago Sul, one of the most affluent neighborhoods in the federal capital, and Sol Nascente, the second-largest slum in Brazil, surpassed only by Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro.

Reducing socioeconomic disparities within municipalities is also a way to strengthen the overall adaptive capacity of urban environments, where more than 87% of Brazilians live. “The work by Gabriela Di Giulio’s group is innovative in analyzing adaptive capacity on multiple scales, not only at the national level but also at the municipal and intramunicipal levels,” says environmental engineer Cassia Lemos, from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), who did not participate in the study coordinated by researchers from FSP-USP. “Identifying the neighborhoods most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change within municipalities enables more efficient and effective mitigation and adaptation measures. This way, we can optimize funding in favor of climate justice at the local level.” Lemos is part of the team at the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) responsible for the Information and Analysis System on the Impacts of Climate Change, better known as the AdaptaBrasil platform.

For climatologist José Marengo, from the National Center for Natural Disaster Monitoring and Alerts (CEMADEN), who was also not involved in developing the UAI, the index proposed by Di Giulio and her colleagues could serve as a valuable tool for assessing the degree of municipalities’ adaptive capacity to climate change. “I’m familiar with similar indices that use environmental and socioeconomic data to calculate cities’ vulnerability to disasters such as landslides and floods, but not to measure their adaptive capacity,” says Marengo. “Although it does not incorporate climate data from municipalities, the UAI can still be useful for shaping public policies in this area.”

The story above was published with the title “Uncontrollable risk” in issue 356 of October/2025.

Project

Advancing the water-energy-food nexus for adaptation to climate change. (n° 20/005697); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Agreement Universities New Zealand/Te Pōkai Tara; Principal Investigator Gabriela Di Giulio (USP); Investment R$31,998.00.

Scientific articles

Di Giulio, G. M. et al. Advancing adaptation of highly heterogeneous urban contexts for improved distributive climate justice: An analysis of specific and generic adaptive capacities of Brazilian cities. Sustainable Cities and Society. July 15, 2025.

NEDER, E. A. et al. Urban adaptation index: Assessing cities readiness to deal with climate change. Climatic Change. May 13, 2021.