Ueslei Marcelino / Reuters / FotoarenaFire in the Corumbá region, in Mato Grosso do Sul, on June 12, 2024Ueslei Marcelino / Reuters / Fotoarena

In most of Brazil, the first half of the year is not typically marred by large forest fires or vegetation fires. Between 70% and 90% of fires are detected in the latter half of the year. Rainfall tends to be more frequent between January and June, which naturally inhibits or reduces the number of fires. The driest months usually occur at the beginning of the second half of the year, especially in July, August, and September. However, the first six and a half months of 2024 tell a different story.

Between January 1 and July 16 of this year, there were about 42,300 fire outbreaks throughout Brazil, which is 50% more than those recorded during the same period in 2023. This data comes from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), which uses observations recorded in the afternoon by NASA’s Aqua Satellite as a reference to track how forest fires are developing across the country. Not since 2003 and 2004, when 56,000 and 47,000 hotspots were recorded over the same period, respectively, have so many fires been observed during a time of the year when fires usually occur less frequently.

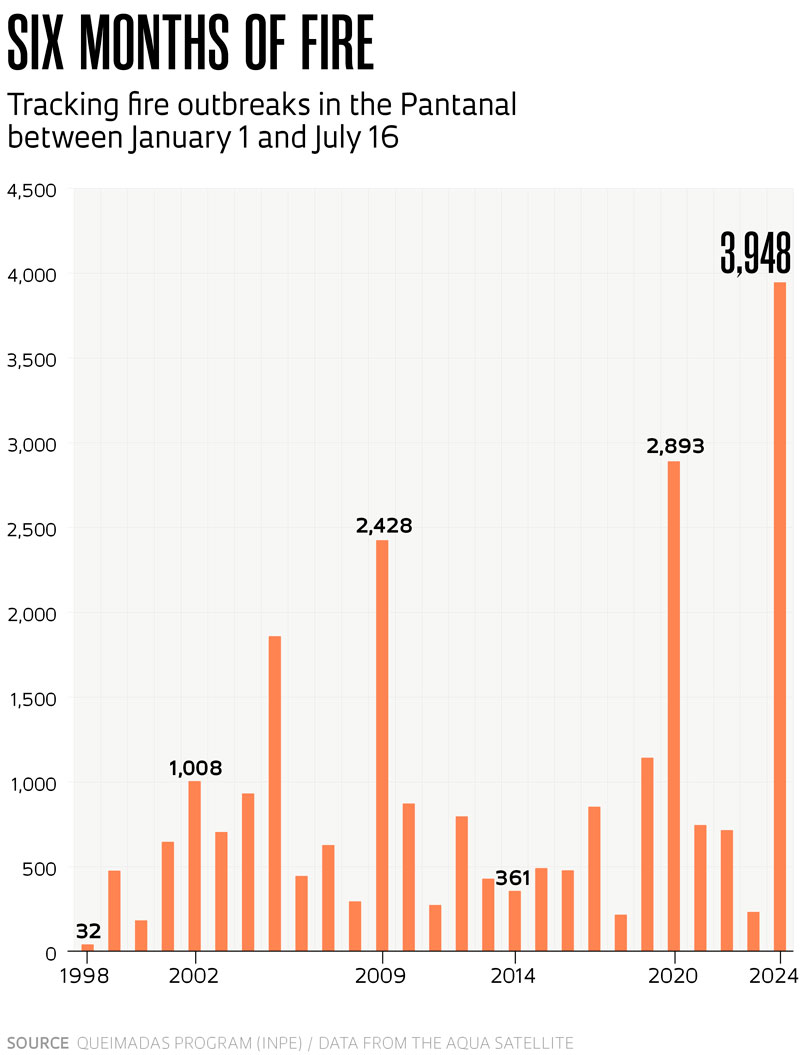

Far and away, the most drastic situation in the first half of the year was observed in the Pantanal, which recorded nearly 3,900 hotspots in the first six and a half months of 2024. This is more than 16 times the number of hotspots observed in the same period in 2023. Never before has this biome, which is home to the largest floodplain on the planet and covers 1.8% of the country, seen so many fires in the first half of the year. According to statistics from the Queimadas Program, run by INPE, which has collected Brazilian biome data since 1988, the maximum number of fires in the first half of the year in the Pantanal was around 2,900 in 2020.

With the exception of the Pampas biome, which is located exclusively in Rio Grande do Sul, a state that experienced massive flooding due to heavy rainfall between the end of April and early May 2024, all biomes recorded an increase in the number of fire outbreaks between January 1 and July 16. Because they are much larger than the Pantanal, which is Brazil’s smallest ecosystem, the Amazon, the Cerrado, and the Atlantic Rainforest had, in absolute numbers, more hotspots in the first half of the year than the large floodplain region. However, proportionally, no other region showed an upward trend even close to that of the Pantanal. The biggest increases were seen in the Amazon (63%), the Atlantic Rainforest (36%), and the Cerrado (24%). Noteworthy is the high concentration of fire outbreaks in February, normally a time of abundant rainfall, in the state of Roraima.

The surge in fire outbreaks in the Pantanal was concentrated in June, with around 3,300 hotspots. Forecasts for the second half of the year are not encouraging. “We are only at the beginning of the drier season and the prevailing trend is for more fires to break out in the second half of the year, not only in the Pantanal, but also in the western Amazon and the Cerrado,” says meteorologist Gilvan Sampaio, general coordinator of INPE’s Earth Sciences department.

A series of factors, some local and others diffuse, explains the rising flames in the biome. The broader backdrop, which impacts the entire planet, is the worsening greenhouse effect, which has made Earth’s climate hotter in recent decades. According to data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service, between July 2023 and June 2024, Earth’s average temperature was at least 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C) higher than the average for the preindustrial period, which corresponds to the second half of the nineteenth century. In December 2023, it was 1.78 °C higher than the average for that month between 1850 and 1990.

It was the first time that the European agency’s system had recorded this level of temperature rise for 12 consecutive months. The previous record was in 2016, when for three months the temperature was 1.5 °C above preindustrial levels. Limiting the increase in global warming over the coming decades to 1.5 °C— a high level, with serious impacts on different parts of the planet, but still considered manageable — is a goal that has been established in international climate agreements but that is becoming increasingly distant.

“The problem is that the temperature in the Pantanal has risen by 3 to 4 °C in the last four decades and flooding in the region’s rivers is weaker,” says meteorologist Renata Libonati, coordinator of the Laboratory for Environmental Satellite Applications at the Department of Meteorology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (LASA-UFRJ). “There was a major drought that lasted from 2019 to 2022, peaking in 2020 and, since April of last year, the rainy season has hardly reached the biome.” The result: current local conditions make the Pantanal more vulnerable to escalating fires.

Data provided by LASA indicate that in June alone, 4,060 square kilometers (km2) of the Pantanal caught fire. This figure represents nearly 2.7% of the biome’s area. It is more than what burned during the same month in the entire Amazon region, which accounts for almost half of Brazil’s territory. In the first half of the year, the area affected by fire outbreaks in the Pantanal reached 7,227 km2, an all-time record in the biome for this period. “We are seeing an increasingly early start to the dry season in the Pantanal,” says Libonati.

Monitoring shows that only 1% of the fires are started by natural causes, such as lightning strikes. The other 99% were caused by human activity. Around 95% of the fires were detected on private properties and only 5% in environmental protection areas or indigenous reserves.

The information released by the MapBiomas project corroborates the LASA and INPE records, albeit with slightly different figures. MapBiomas is a civil initiative that works as a collaborative network of over 70 nongovernmental organizations, universities, and technology startups that, since 2015, has produced annual data and maps on land cover and land use in Brazil. According to one of its tools, the Fire Monitor, fires in the first half of the year in the Pantanal affected 4,680 km2. Almost 80% of the fires occurred in June.

Alan Chaves / AFP via Getty ImagesFire in the city of Cantá, in Roraima, in February of this yearAlan Chaves / AFP via Getty Images

Similar to INPE’s records, the area around the city of Corumbá, in Mato Grosso do Sul, was the focal point for the fire outbreaks observed by the MapBiomas system. “The biome’s vegetation is quite dry, so the fire catches and spreads easily,” says the organization’s geographer, Mariana Dias. On top of destroying vegetated areas, recurrent droughts in the Pantanal have put pressure on the animal populations that inhabit the region. A recent study by Brazilian researchers indicates that some species, such as the tapir (Tapirus terrestris) and the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), have seen their population numbers drop tenfold after the major fires in 2020 (see report).

River levels is another sign that the region is in dire straits. A report issued by the Geological Survey of Brazil (SGB) on July 10 highlights that several stretches of the Paraguay River, the Pantanal’s largest river, reached critical water volume levels. In Cáceres, a city in Mato Grosso that is near the river’s headwaters, water levels reached 70 centimeters (cm), 1.3 meters (m) lower than expected for that time of year. Also on July 10, the gauging station in Porto Murtinho, in Mato Grosso do Sul, where the Paraguay River crosses Brazil’s border, recorded a level of 1.73 m. At this point, the historical average is 5.28 m for the period. “We have recorded levels close to or below the historical lows for the period at virtually all stations monitored in the basin,” warned chemical engineer Mauro Campos Trindade, of the SGB in a press release issued by the agency.

All eyes on the Amazon

During the second half the year, it is likely that more attention will be focused on the country’s two largest biomes, the Amazon and the Cerrado. Together, they cover nearly three-quarters of Brazil’s territory. “The fight waged on fires in the Pantanal in June has already reduced the number of fire outbreaks in July, although we are only now entering the historically drier months,” says Sampaio. “But the situation in the western Amazon and the Cerrado is worrying.”

The dry season seems to start earlier and end later in many parts of Brazil, especially in the central-northern part of the country. Instead of the rain stopping in May, the drought sometimes begins in April and lasts until November. Because some of the Amazon’s moisture is transported by air to the country’s other biomes via the so-called flying rivers, what happens in the large rainforest affects the climate in areas thousands of miles away. If rainfall is delayed in the Amazon, the rest of the country remains dry as well.

The issue of rising atmospheric temperatures is another cause for concern. “In certain regions of the Amazon, such as Acre and part of Rondônia, the average mid-year temperature is 3 °C higher than the historical average,” says the INPE researcher. In addition to global warming, another factor that influences thermometer fluctuations on land is ocean behavior. Significant warming or cooling of Pacific and Atlantic Ocean surface water can generate more or less rainfall in different parts of the country. Right now, the equatorial Pacific seems to be at normal temperatures or heading toward cooling (La Niña). The equatorial Atlantic, on the other hand, is warming, which could bring more rain to the north of the Amazon by the end of the year.

The story above was published with the title “The Pantanal on fire” in issue 342 of august/2024.

Republish