Since August, a new inoculant technology has been available on the market that promises to reduce operating costs and improve yields on Brazilian farms. The inoculant—a liquid biological product containing living microorganisms—is designed to facilitate uptake of phosphorus by crop plants. The new product was developed by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) in collaboration with agritech firm Bioma, in southern Brazil. The commercial launch of the product, christened BiomaPhos, could help to reduce Brazil’s dependence on imports of phosphate (phosphorus-rich) fertilizers in the future.

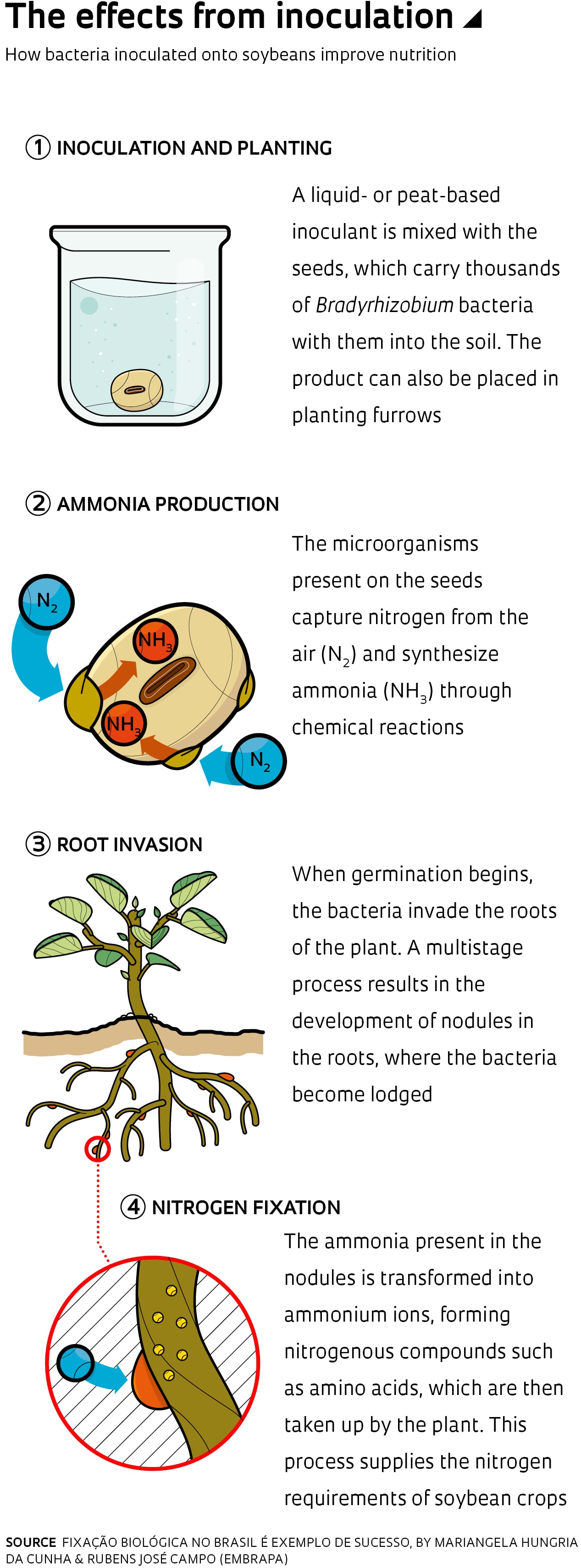

Inoculation technology is not new to Brazilian farmers. Estimates indicate it is used in more than 28 million hectares of soy fields, or about 80% of Brazil’s total soy crop. The most widely sold inoculant product, composed of nitrogen-fixing bacteria, can be used to fully or partially replace the use of nitrogen fertilizers in soy and bean plantations. The newly launched inoculant enhances uptake of phosphorus, another important nutrient, minimizing the requirement for chemical fertilizers. Together with nitrogen (N) and potassium (K), phosphorus (P) forms the triad of essential plant nutrients. These will be found in most common fertilizer formulations, designated as NPK.

“BiomaPhos is the crowning achievement of a research project initiated 18 years ago,” says microbiologist Christiane Abreu de Oliveira Paiva, of the EMBRAPA Maize and Sorghum division in Sete Lagoas, southeastern Brazil. Similar products have long been available for temperate countries like the US, Canada, and Argentina, but none developed specifically for Brazil’s climate. EMBRAPA’s effort to create a dedicated inoculant for local agriculture came in response to the often-poor performance of imported inoculants designed for use in the countries where they are produced, which often differ in soil and climate from Brazil’s farmland. In addition, Brazil’s tropical climate means phosphorus occurs in the soil in association with chemical elements not always found in temperate nations.

Paiva and colleagues from EMBRAPA initially isolated 450 microorganisms capable of solubilizing the phosphorus found in clays and organic matter present in the soil. “We narrowed those 450 to a shortlist of 15 and tested them on sorghum, maize, and other crops. We then selected the five most productive bacteria for field trials,” says the researcher. After demonstrating that yields are effectively improved, EMBRAPA signed a contract with Bioma to produce the inoculant. Two bacteria—Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus megaterium—were selected for the BiomaPhos product.

The inoculant has initially been registered for use on maize crops, and has been shown to increase yields by 14 to 20 bushels per hectare, according to EMBRAPA. “The product improved both phosphorus nutrition and yield stability by increasing tolerance to water stress,” says crop scientist Luís Eduardo Curioletti, who manages an experimental station operated by Agrum Agrotecnologias Integradas, one of the companies engaged to validate the product.

“We’ve been surprised by the level of adoption within a short period of product launch,” says Paiva. She explains that the bacilli in the inoculant interact with phosphorus contained in soil or chemical fertilizers. “Acids and enzymes released by the bacteria help to break down phosphorus molecules that are present in the soil in forms that are unavailable to plants,” says the EMBRAPA researcher. Phosphorus does not occur as a free element in nature; it is usually associated with oxygen atoms and forms compounds called phosphates.

“Bacteria are able to solubilize these phosphates,” explains agronomist Maria Catarina Megumi Kasuya of the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) in Minas Gerais. “They can take phosphate from rock, for example, and make it soluble for use by both the plant and the microbe itself.” Because Brazil’s soils are generally poor in phosphate, this type of inoculant is not a replacement for phosphate fertilizers, but can reduce the amounts required.