A new graduate studies model is set to debut in 2025 as a pilot program across six public universities in São Paulo State, Brazil. The initiative is reformulating master’s degree programs with a far more flexible structure than the conventional approach. In the first year, depending on the university, students will follow an interdisciplinary curriculum with courses on topics such as entrepreneurship and addressing societal issues. They will also be encouraged to engage in outreach activities tied to their research areas. Concurrently, students will design their research proposals and select academic advisors—steps that traditionally occur prior to admission.

After completing the 12-month cycle, students will undergo a committee evaluation and choose from different academic pathways. High-performing students with outstanding research proposals may either extend their studies for an additional year to complete a master’s thesis or transition directly into a PhD program to be completed in four years. A third option, for students whose performance is deemed insufficient, is to conclude their studies after the first year and receive a specialization diploma.

The new academic pathway was formalized in November through a memorandum of understanding signed by representatives from the six universities—the University of São Paulo (USP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo State University (UNESP), the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), and the Federal University of ABC (UFABC)—alongside heads of the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) and the FAPESP Board of Trustees. The pilot will roll out over the next five years, targeting a select group of graduate students. Only master’s and doctoral programs with CAPES’s top evaluation scores of 6 and 7 will be eligible to participate—representing roughly 30% of the programs at the six universities. Participation in the new track is voluntary, and not all eligible programs are expected to adopt the model. The current direct-entry PhD pathway—allowing undergraduate students to transition directly into a doctorate program without first completing a master’s degree—while seldom used, will remain available to all programs, irrespective of their adoption of the new model.

In the pilot phase, the option to transition from a master’s to a PhD after 12 months will be limited to a predefined number of CAPES fellowships originally designated for master’s students, which can be converted into CAPES PhD fellowships, with FAPESP providing supplementary grant funding to bring the total amount in line with its standard grant amounts. In practical terms, each graduate program will be entitled to no more than one or two of these PhD fellowship grants. For example, UNICAMP will be allocated 35 fellowships annually, distributed among its 37 programs rated at 6 or 7. In the short term, the impact will be minimal for an institution that graduated 747 PhDs and 1,113 master’s students in 2023.

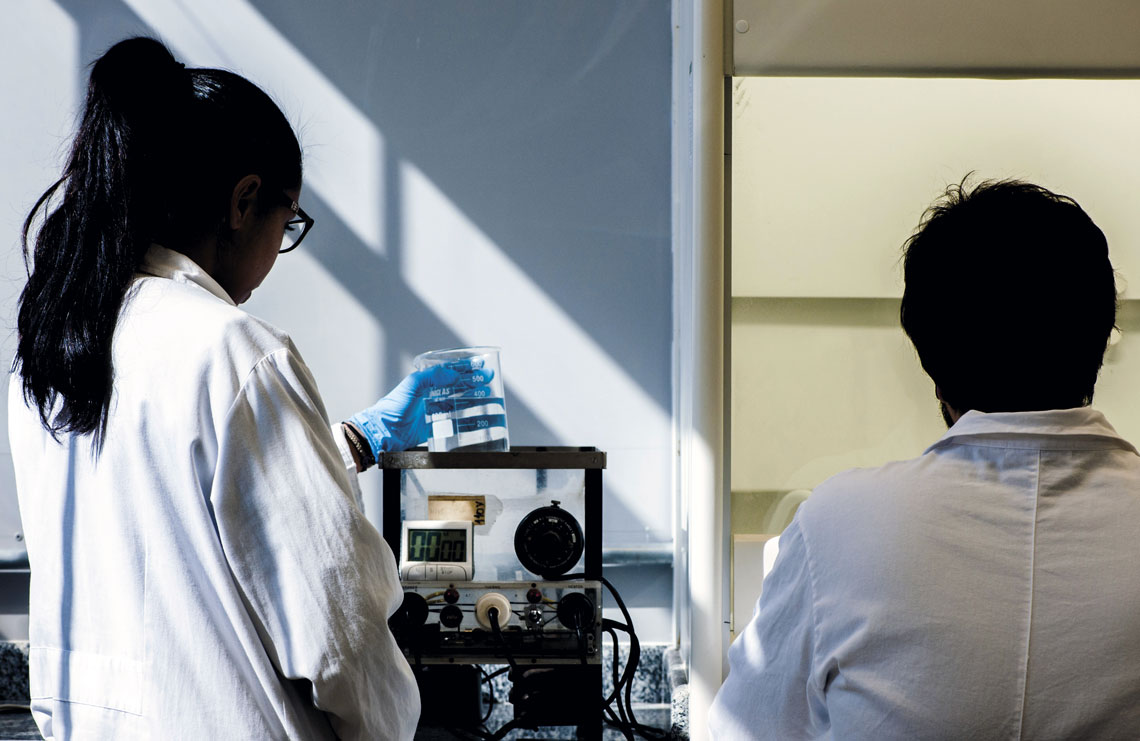

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FapespThe USP Developmental Genetics Laboratory: PhD recipients at the university earn their degrees at an average age of 37Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa Fapesp

Luiz Antonio Pessan, a materials engineer and director of programs and fellowships at CAPES, explains that the overarching goal is to make graduate programs more appealing to students and increase the number of doctoral graduates. “Brazil currently produces 10 PhD graduates per 100,000 people, compared to an average three times higher in OECD-member industrialized nations,” he notes. While Brazil has met the targets outlined in its last National Graduate Education Program—producing 25,000 PhDs and 60,000 master’s graduates annually—the system has recently lost momentum. The number of degree earners has diminished, partly due to the pandemic, and fewer candidates are applying for programs. These trends suggest that the current model is nearing exhaustion, even as recent data points to a gradual recovery (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 315). Factors contributing to this decline include the lengthy duration of doctoral programs (PhD recipients in Brazil earn their degree at an average age of 38, compared to 31 in the US) and the heavily academic focus of the curricula, which is less appealing to those seeking careers in industry, public institutions, or nongovernmental organizations.

The new model is designed to address these issues. “Today, the average age for completing a PhD is 38, yet Brazil’s lengthier programs have not yielded better outcomes. We need to change this by streamlining processes, cutting bureaucracy, and eliminating unnecessary barriers to training good researchers,” said Marco Antonio Zago, chairman of the FAPESP Board of Trustees, during the program’s launch. According to Simon Schwartzman, a sociologist with the Institute of Economic Policy Studies in Rio de Janeiro, the new program could help address what he sees as a significant anomaly in Brazil’s higher education system. “In Brazil, direct-entry PhD programs remain rare, due to the belief that a master’s degree is an essential prerequisite for a PhD. This is a Brazilian aberration, especially as master’s programs are increasingly pursued by professionals seeking to improve their qualifications for the job market rather than continuing to a PhD. A PhD is intended for those entering research and requiring deeper training, but this path becomes unnecessarily long when preceded by a master’s degree,” he explains.

Hematologist Rodrigo Calado, USP’s associate dean for graduate student affairs, notes that speeding up the production of PhDs in Brazil is advantageous for multiple reasons. “For Brazil’s society and economy, having highly skilled researchers entering the workforce sooner—whether in academia, public service, or industry—is important. Starting their careers earlier also ensures a quicker return on the investment in their education,” he notes. Shorter pathways allow young PhDs to join the workforce, start building their careers, and support their families by the age of 30, reducing uncertainties and dependence on grants. Calado reports that the university’s PhD graduates earn their degrees at an average age of 37—one year younger than the national average. “If we can bring that down to 34, it would be a significant improvement, but better yet would be 31 as in the US. People’s peak scientific productivity typically occurs around age 30,” he notes. “The current system is highly discouraging. Imagine choosing a career knowing you might not secure employment until you’re nearly 40.” Of USP’s 262 graduate programs, approximately 50, with scores of 6 or 7, qualify to test the new model.

At UNIFESP, 13 graduate programs in the health sciences—associated with the São Paulo School of Medicine and the São Paulo School of Nursing—are eligible to implement the new model. According to architect and urban planner Fernando Atique, the institution’s associate dean for graduate education and research, the new pathway could have a meaningful impact. “Medical training, in particular, is an inherently lengthy process. Beyond undergraduate training, future doctors must complete a residency. Many physicians delay pursuing a master’s degree, and most only pursue a doctorate much later, after establishing their careers. If they could complete graduate studies by age 30, it would be a significant benefit,” he says. Atique also highlights that many of UNIFESP’s PhD graduates come from other states. “Younger PhDs with more up-to-date skill sets would be better positioned to pass competitive exams and add value to their host institutions, and would have the opportunity to work at leading clinical centers or in the pharmaceutical industry.”

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPResearchers at UNICAMP’s Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center: the university graduated 747 PhDs and 1,113 master’s students in 2023Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

At UFSCar, eight programs may adopt the new model: four in the humanities, three in the exact sciences, and one in health sciences. “Each program will decide whether or not to participate. We already have experience with direct-entry PhD pathways in engineering and some areas of health sciences, but not in the humanities, where research and doctoral training tend to require longer maturation periods,” explains sociologist Rodrigo Constante Martins, UFSCar’s associate dean for graduate student affairs. Given the seven annual fellowships allocated to UFSCar, Martins estimates that 28 doctoral students will benefit during the four-year pilot program, only a fraction of the roughly 350 PhDs the university confers annually. “We hope the pilot is successful and that funding increases over time, allowing us to benefit more students beyond this initial cohort.”

Political scientist Rachel Meneguello, associate dean for graduate student affairs at UNICAMP, believes master’s students will experience the most noticeable changes. “Our proposition is that incoming students have a more interdisciplinary curriculum, develop their research projects, and take external internships. Our intention is not to create professional master’s programs but instead to make graduate training more closely aligned with the professional world,” she explains, adding that the outcomes from fast-tracked PhDs will only be felt in the long term, as expanding the number of students pursuing direct-entry PhDs has historically proved challenging. “Only exceptionally well-prepared students can be awarded an opportunity like this,” she notes. “Fields like dentistry, computer science, and some branches of engineering are showing greater interest in the new format because they already offer more applied master’s programs, while other fields are still assessing the model.”

In 2022, UNESP began revamping its graduate curricula to provide more comprehensive training. “We added courses on ethics, entrepreneurship, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals to our curriculum portfolio, with some offered in hybrid formats so that UNESP students across various cities could attend,” explains chemist Maria Valnice Boldrin, the university’s associate dean for graduate student affairs. “This new program goes a step further by introducing a pathway that includes off-campus activities. It not only reduces the time required to earn a PhD but also improves the quality of master’s-level training.”

In mid-2024, São Paulo’s three state universities convened to discuss joint proposals for transforming the graduate education model to better attract students (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 340). “We quickly understood that meaningful reform would require support from CAPES and FAPESP. FAPESP’s involvement is important because it reinforces the role of graduate programs in research,” says Boldrin.

According to Pessan of CAPES, representatives from other Brazilian states have already reached out to the federal agency to explore adopting the new model with backing from their respective state research funding agencies. “What’s important is that we encourage programs to evolve further. The graduate education system cannot afford to stagnate,” he says. Pessan notes that CAPES is closely monitoring any shifts in program performance metrics resulting from the new model to ensure these changes do not adversely affect programs during the four-year evaluation cycle.

The story above was published with the title “A flexible new pathway” in issue 347 of january/2024.

Republish