“The most daring project developed by man since Apollo,” the series of space missions coordinated by NASA between 1961 and 1972. That’s how Manchete magazine described the RadamBrasil project on October 23, 1976, reflecting the pride of the time. The occasion marked the release of the first Amazon mapping results. Launched in 1975, RadamBrasil was an expansion of the earlier Radam project (short for Radar na Amazônia, or Radar in the Amazon), created five years earlier. It marked the beginning of an even more ambitious undertaking: to map the entire Brazilian territory and its natural resources.

As they explored vast, uncharted regions of the country, the project’s researchers had reason to feel like the pioneers of the Apollo program. “We were in a demographic void, surrounded by untouched nature,” recalls geologist Pedro Edson Leal Bezerra, of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in Pará. He joined the RadamBrasil project in 1977 and remained until its conclusion in 1986, when IBGE absorbed the team and the data it had collected.

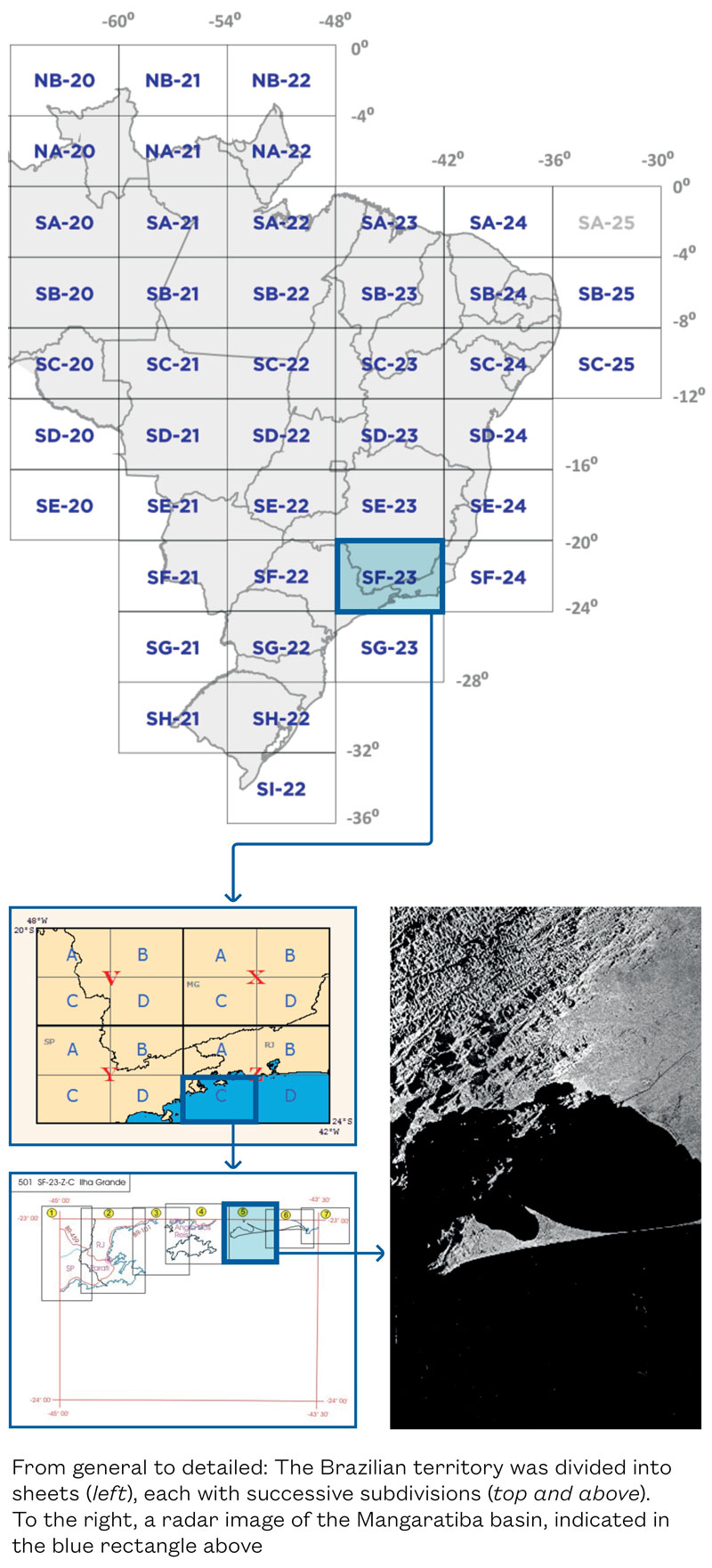

Bezerra participated in interpreting the radar images. A side-looking radar, manufactured by the American company Goodyear, with a spatial resolution of 16 meters, had been installed on a Caravelle aircraft—a short- and medium-range jet that flew at an altitude of 12 kilometers (km) and a speed of 700 km per hour. The radar’s microwave transmission and reception antenna were located in the belly of the aircraft. “We did the visual interpretations and selected the points for field verification. The Logistics Department flew over and chose a location where the camp would be set up, and we could stay there for up to three months,” he recalls.

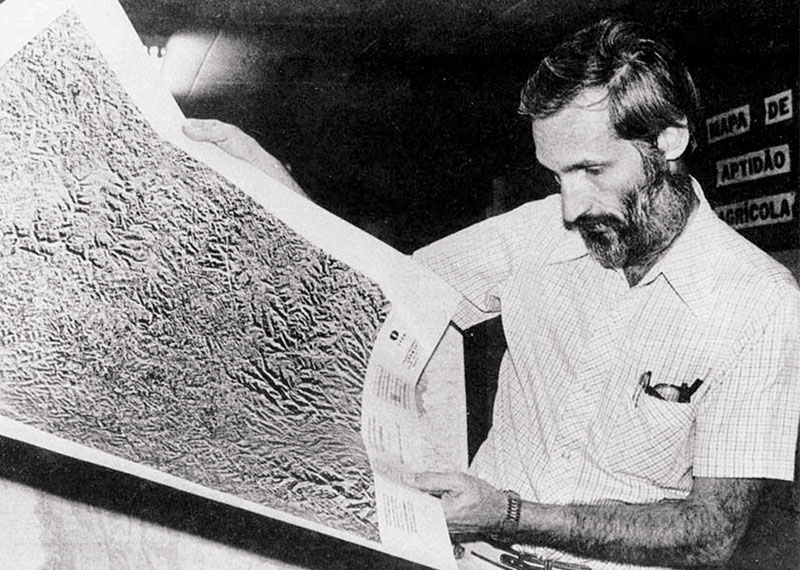

INPE Joaquim Barbosa, from the Navy, examines a RadamBrasil map in the mid-1970s to accurately demarcate the country’s bordersINPE

In the field, they collected samples of rocks, minerals, and soil. There were also teams focused on vegetation. “We measured trees and collected plant samples, which were later identified and classified by a botanist,” summarizes forest engineer Joana D’Arc Ferreira, from IBGE in Pará, who worked on Radam from 1974 to 1986. “Since 1977, IBGE maintained an herbarium in the Roncador Ecological Reserve in the Federal District and later incorporated the RadamBrasil collection.” Located in Salvador since 1980, the herbarium holds around 52,000 plant specimens, mainly from the North and Northeast.

RadamBrasil brought together around 800 professionals. “We were practically hunted down in graduate programs at universities—mainly the federal universities of Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and Pernambuco, as well as the University of São Paulo,” says Jurandyr Ross, a retired geographer from USP, who worked on the project from 1977 to 1983 in the Midwest and southern Amazon.

This large-scale mobilization led to many discoveries—such as the 1976 identification of an estimated 3 billion tons of niobium reserves in Seis Lagos hill, Amazonas, one of the largest deposits in the world. It also highlighted areas susceptible to erosion and regions well-suited for building hydroelectric plants. “We didn’t even know the exact course of the Amazon River,” says geologist Mário Ivan Cardoso de Lima, who joined Radam in 1971 and stayed until his transfer to IBGE, where he worked for another 34 years before retiring. He later compiled his experiences in the book Projeto Radam: Uma saga amazônica (The Radam Project: An Amazonian Saga) (Belém, Paka-Tatu, 2008).

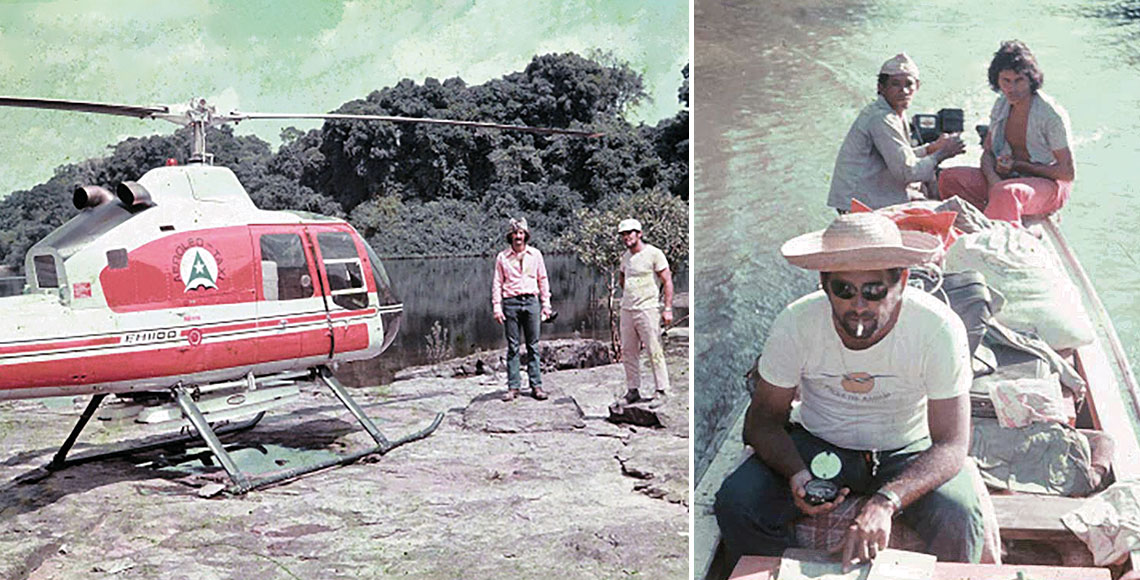

Mário Ivan Cardoso de Lima / IBGE. Desbravar, Conhecer, Mapear. 2018Researchers in the field arrived at radar-indicated locations either by compass, as in the Madeirinha River (AM) in 1974, or by helicopter, as in the Iriri River (PA) in 1976Mário Ivan Cardoso de Lima / IBGE. Desbravar, Conhecer, Mapear. 2018

Partnership with NASA

Radam’s connection to NASA goes beyond mere boastful comparison. According to Lima, the project’s origins can be traced to a 1965 partnership between the US space agency and the National Commission for Space Activities (CNAE), the forerunner of today’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). “NASA proposed a collaboration in the field of remote sensing, which would be used in lunar studies,” he explains. This gave rise to Project Sere—an acronym for Remote Sensing—initially focused on the Iron Quadrangle in Minas Gerais, using data from various remote sensors, including radar. The success of that effort paved the way for its expansion to the Amazon and eventually to the entire country.

“Sere included Radam, but it was later transferred to the Ministry of Mines and Energy,” says INPE geographer Evlyn de Moraes Novo, a pioneer in satellite-based environmental monitoring. From then on, the two initiatives proceeded separately: the Satellite Remote Sensing Program, which used data from the ERTS (Earth Resources Technology Satellite, later renamed Landsat) series, and the Amazon Radar project.

The use of radar for mapping the Amazon was a strategic choice, due to the region’s persistent cloud cover. “Optical satellite sensors operate in the visible spectrum and rely on sunlight reflected from the Earth’s surface. They cannot penetrate clouds,” explains INPE geographer Hermann Kux, who worked on RadamBrasil from 1977 to 1980. Radar, by contrast, emits electromagnetic waves that bounce off the surface and return to the receiver, making it effective even in cloudy conditions, both day and night, as it does not depend on sunlight.

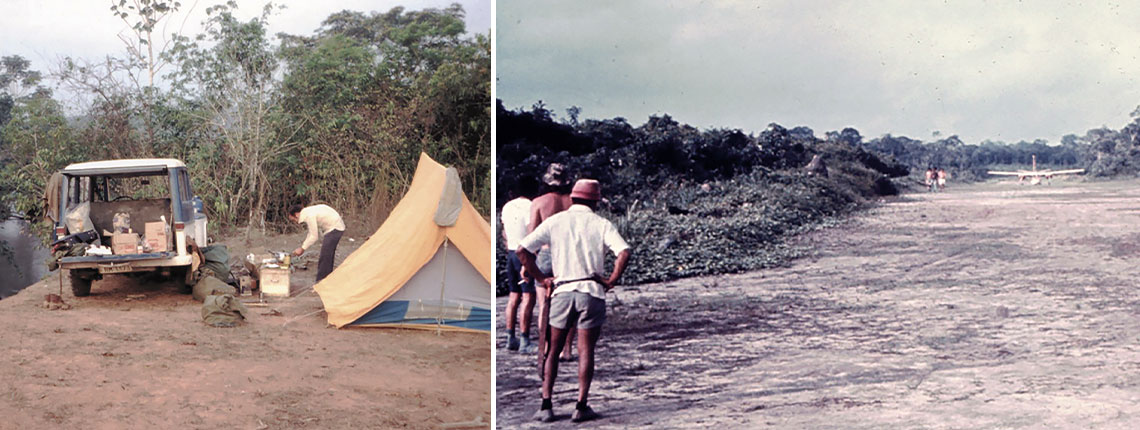

Virlei Álvaro de Oliveira / IBGE | Jaime Heitor Lisboa Pithan / IBGE. Desbravar, Conhecer, Mapear . 2018Soil research team camp, set up on the banks of the Von Den Steinen River (MT) in 1979 and a landing strip used in 1977 (location unspecified)Virlei Álvaro de Oliveira / IBGE | Jaime Heitor Lisboa Pithan / IBGE. Desbravar, Conhecer, Mapear . 2018

The mapping was organized into five thematic areas, each handled by a dedicated team: cartography, geology, terrain, soils, vegetation, and potential land use. These areas cross-referenced data to determine the most appropriate uses for each region. Understanding Brazil’s natural resources was a strategic goal of the military government, which in 1970 launched the National Integration Program (PIN). Its slogans—“Integrate so as not to surrender” and “Land without men for men without land”—reflected its aim: to occupy the Amazon using labor from northeastern migrants displaced by drought. The construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, initiated in 1970, was part of this broader objective (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 309).

Historian Leandro Cruz, who is studying the Radam project as part of his doctoral research in the history of science and health at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (COC-FIOCRUZ), points out that another motivation was to grant companies the right to exploit the region. “The project’s reports weren’t publicly accessible; some were classified. But business associations could request them from the government,” he notes. “By granting private companies these rights, the state offloaded some of its responsibilities in the colonization process.”

Interpreting the Images

Like mapping the land itself, interpreting radar images was a puzzle to be solved. “There was no defined methodology. We used to compare the images while the plane was still in flight,” says Lima. The black-and-white radar images couldn’t be read the same way as conventional aerial photographs. “You might see a light-colored area and assume it’s sand, but that’s not how the equipment works. White simply indicates high reflectance [how much energy is reflected back] which could be a mangrove swamp, for example,” he explains.

Different types of vegetation responded differently to the radar waves. During his PhD, completed in 1995 at the Federal University of Pará, Lima developed a methodology to correct common misinterpretations of radar images. His work helped resolve long-standing issues and resulted in two books: Introdução à Interpretação Geológica de Radar (Introduction to the geological Interpretation of radar; IBGE, 1995) and Geologia de Radar – Sistemática dos Elementos Radargráficos (Geology of Radar—Systematics of Radargraphic Elements; Self-published, 2017).

The government had high hopes for the mapping project. In his recently published book O Brasil na era espacial (Brazil in the space age; Editora Viseu, 2025), geologist Raimundo Almeida Filho, who followed the project as a researcher at INPE, recalls that in March 1971, then-Minister of Mines and Energy Antônio Dias Leite (1920–2017) presented Radam to President Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1905–1985), claiming it would aid in oil exploration: “The minister told the president that radar signals penetrated up to 10 meters into the ground—which is false. Radar signals are indiscriminately reflected by surface features and vegetation.” Even if penetration were possible, Almeida notes, it would offer little value for oil exploration.

“At that time, all we had were images and hypotheses,” adds Ross. The radar images, produced at a scale of 1:250,000 (where 1 centimeter equals 2.5 km), showed terrain in a rough pattern, which allowed researchers to associate certain surface features with soil types and speculate about possible mineral deposits below. But the images alone couldn’t confirm anything. “There’s no magic in the image,” he says. “Fieldwork was essential to reaching accurate conclusions.”