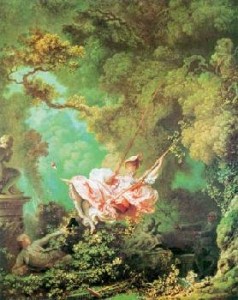

REPRODUCTIONS FROM THE BOOK THE "INVENTION OF LIBERTY", JEAN STAROBINSKI/ "THE SWING", JEAN-HONORÉ FRAGONARDHe achieved the feat of being incarcerated by the three regimes that France experienced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the Old Regime, at the request of Louis XVI; the French Revolution, under the leadership of Robespierre; and the Restoration, when he was jailed by Napoleon and died in prison. For someone who spent most of his life behind bars, Donatien-Alphonse François de Sade (1740-1814), the Marquis de Sade, achieved impressive notoriety, which posterity, as a result of its limited understanding of who he really was, vulgarized further, by transforming him into a vague synonym for “perversion.” “The psychopathological reading is not wrong, but it is only one among the many possible readings of Sade: he is not merely this. He is also this,” states historian Gabriel Giannattasio, a senior professor from UEL, the State University of Londrina and author of Sade: um anjo negro da modernidade [Sade: a black angel of modernity] (Editora Imaginário publishing house, 208 pages, R$ 26). He has recently also released Cartas de Vincennes: um libertino na prisão [Letters from Vincennes: a libertine in prison] (Eduel, 154 pages, R$ 35), a book that brings together 16 letters written by Sade in jail, from 1777 to 1784, in the castle prison at Vincennes, the destination of fallen noblemen and victims of the lettres de cachet, documents issued by the king to imprison those seen as “undesirable”, such as the Marquis. For the first time, a full version of the letters is published in Brazil. Their chief addressees were Renée, the writer’s first wife; Madame Montreuil, the “sadistic” mother in law who detested the libertine; and Mademoiselle Rousset, a close friend of the nobleman and his interlocutor.

REPRODUCTIONS FROM THE BOOK THE "INVENTION OF LIBERTY", JEAN STAROBINSKI/ "THE SWING", JEAN-HONORÉ FRAGONARDHe achieved the feat of being incarcerated by the three regimes that France experienced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the Old Regime, at the request of Louis XVI; the French Revolution, under the leadership of Robespierre; and the Restoration, when he was jailed by Napoleon and died in prison. For someone who spent most of his life behind bars, Donatien-Alphonse François de Sade (1740-1814), the Marquis de Sade, achieved impressive notoriety, which posterity, as a result of its limited understanding of who he really was, vulgarized further, by transforming him into a vague synonym for “perversion.” “The psychopathological reading is not wrong, but it is only one among the many possible readings of Sade: he is not merely this. He is also this,” states historian Gabriel Giannattasio, a senior professor from UEL, the State University of Londrina and author of Sade: um anjo negro da modernidade [Sade: a black angel of modernity] (Editora Imaginário publishing house, 208 pages, R$ 26). He has recently also released Cartas de Vincennes: um libertino na prisão [Letters from Vincennes: a libertine in prison] (Eduel, 154 pages, R$ 35), a book that brings together 16 letters written by Sade in jail, from 1777 to 1784, in the castle prison at Vincennes, the destination of fallen noblemen and victims of the lettres de cachet, documents issued by the king to imprison those seen as “undesirable”, such as the Marquis. For the first time, a full version of the letters is published in Brazil. Their chief addressees were Renée, the writer’s first wife; Madame Montreuil, the “sadistic” mother in law who detested the libertine; and Mademoiselle Rousset, a close friend of the nobleman and his interlocutor.

“These letters deepen the Sade mystery and unveil his thinking behind the scenes, the antechamber, the experimental and productive industry of the man Sade. It is through his letters that he communicated with the universe around him and this communication exercise enabled him to test his thoughts and to develop his philosophy,” notes the researcher. In writing them, he is not the author of Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom or The 120 Days of Sodom. “The Marquis is not yet the man of letters whose career began late in life. The prison letters, however, foretell his ideas and the imaginative vigor that will develop freer forms in his novels. The correspondence from Vincennes is the richest that has survived for us, being far superior to the letters that he subsequently wrote from 1784 to 1789 from the Bastille, which are, generally speaking, bureaucratic,” he explains. According to the professor, this reveals a dislocation in the channels of expression of the notorious libertine. “His literary energy is forcefully dislocated to his works and to the privileged period of this philosophical and literary production, using a range of forms and genres.” In these letters, one can see the libertine intellectually becoming a radical libertarian, capable even of questioning the Enlightenment,of which he was from the beginning a follower – by resorting to his own enlightened arguments (which the followers of the Enlightenment did not dare to put into practice) – shatter the movement’s framework and reinvent it drastically. “According to you, my way of thinking cannot be approved. So what? Insane is he who embraces a way of thinking to please others! My way of thinking is the fruit of my reflections, the product of my existence and organization. This way of thinking that you disapprove of is the only consolation in my life; it alleviates my pain in prison, it comprises all my pleasures in the world, and it is more important than my life. It was not my way of thinking that brought about my unhappiness, but that of other people,” he writes to his wife. “These writings envelop the enigma and already contain the characters and themes of the Sade novel. In his cell, Sade was an exemplary observer, or better said, an exemplary experimenter,” notes the author.

THE STOLEN KISS, DETAIL/JEAN-HONORÉ FRAGONARDHe had plenty of time for this. “For a prisoner, correspondence abolishes distance. For a prisoner such as Sade, who ignored the extension of his penalty, this perception was imperious. During the 13 years he spent at Vincennes, the Marquis stated so intensely the wish to ‘abolish distance’ that he transformed this into a sovereign principle of his literature,” explains Eliane Robert de Moraes, head professor of Esthetics and Literature at PUC-SP and author of several essays on the erotic imagination in literature, including Sade: a felicidade libertina [Sade: Libertine happiness] (Iluminuras) and O corpo impossível [The impossible body] (Iluminuras/FAPESP). “It was during this first period of imprisonment that Sade’s literature emerged, its first effort being Dialog between a priest and a dying man, from 1782, followed by the monumental The 120 days of Sodom, written in 1785 from within the Bastille. Although these already contain the entire underpinnings of his literature, they nevertheless do not fail to remind us of the same face-to-face experience that the correspondence provides.”

THE STOLEN KISS, DETAIL/JEAN-HONORÉ FRAGONARDHe had plenty of time for this. “For a prisoner, correspondence abolishes distance. For a prisoner such as Sade, who ignored the extension of his penalty, this perception was imperious. During the 13 years he spent at Vincennes, the Marquis stated so intensely the wish to ‘abolish distance’ that he transformed this into a sovereign principle of his literature,” explains Eliane Robert de Moraes, head professor of Esthetics and Literature at PUC-SP and author of several essays on the erotic imagination in literature, including Sade: a felicidade libertina [Sade: Libertine happiness] (Iluminuras) and O corpo impossível [The impossible body] (Iluminuras/FAPESP). “It was during this first period of imprisonment that Sade’s literature emerged, its first effort being Dialog between a priest and a dying man, from 1782, followed by the monumental The 120 days of Sodom, written in 1785 from within the Bastille. Although these already contain the entire underpinnings of his literature, they nevertheless do not fail to remind us of the same face-to-face experience that the correspondence provides.”

“Yes, I confess, I am a libertine: I have conceived of everything that is conceivable in this area, but I certainly have not done everything I have conceived of and never shall. I am a libertine, but not a criminal, an assassin,” he confesses in one of his letters. It is a fine profession of his faith. “Sade’s literature expresses, more than any other, a sort of ‘hypermorality’. In other words, it is the type of thinking that tries to uncover, by artistic creation, that from which reality turns away. To conduct this exploration, he turns his back on ethics and morality, discarding humanistic lines of discourse. He aims to listen to the voice of the torturers, considering their motives and even their lack of motive, in order to achieve an understanding of evil. But pay attention: this is the understanding of it, rather than the practice thereof,” warns the researcher. At the limit, Eliane observes, the relation between knowledge and action is at the core of the discussion, because Sade’s detractors, such as the three regimes that incarcerated him, although they attacked his discourse, often put it into practice. “To the point of exceeding his refinements. Unfortunately, when it comes to Sadism, human history is far more prodigal than Sade’s literature.” After all, the word libertine is derived from the Latin libertinus, the precise meaning of which is a person free from slavery or from any social and moral preconception or convention.

“In Sade’s case, it is impossible to distinguish between the libertine and the libertarian. Politics and morals, in this case, are Siamese twins and mean the same to the philosopher and the writer. The literary option of Justine’s creator demands particular attention, given that fiction was his privileged form of expression,” observes Eliane. “By dislocating philosophical reflection to the libertine alcove, the Marquis was forced to take into account the differences between each of the ‘caprices of nature’ that form part of his interminable catalog. As a result, he was obliged to exceed the boundaries of philosophy in the certainty that only literature would allow him to enter the limitless territory of erotic imagination,” she analyses. The researcher also reminds us that it is significant that one of Sade’s most important books, Philosophy in the bedroom, associates, starting with the very title, philosophical thought with libertine practices. “What is in question is not a philosophy of the bedroom, but philosophy in the bedroom. The difference is subtle but essential,” she explains. Indeed, it is so important that it allowed the unlikely but brilliant “convening” of the Marquis and Machado de Assis, as conducted by the researcher. Eliane Robert notices “familiar” echoes between Sade’s literature and Machado de Assis’s short story, A causa secreta [The secret cause] (1885), best known for its terrifying description, oddly rich in details (an uncommon feature for Machado de Assis) of the literally sadistic pleasure of the character Fortunato in torturing a rat. “Although they are very different writers, both want to delve into the false compartment that is our humanity,” explains the professor. “After all, if the point of view of Sade’s narrators always coincides with the conscience of his perfidious libertines, what happens in Machado de Assis’s short story is not far from this model.” The “vast, quiet and profound pleasure” (a phrase from the short story), notes Eliane, also reminds us of the loneliness of the Sade characters. This is the case, for instance, when Fortunato sees a friend, an eyewitness of the atrocities inflicted upon the rat, crying by his deceased wife’s coffin, thus revealing a hidden and adulterous passion. At that moment, notes the researcher, Fortunato’s face, upon learning he had been betrayed, but nevertheless “revenged”, reflects the same expression of pleasure elicited from him while torturing the rodent, except that his enjoyment is now derived from his friend’s suffering.

THE NIGHTMARE, DETAIL /JOHANN HEINRICH FÜSSLI“In Sade, all and any argument, no matter how rational it may be, ends up engulfed by fantasy, and in such a way that it is finally offered up to the reader as a hallucination. Nothing could be further away from Machado de Assis’s outstanding psychological realism,” she observes. The comparison, she adds, allows one to grasp the distance between literature that works with types, as is the case of the Marquis’s characters, and literature geared toward particular aspects of its characters, this being the characteristic of the great nineteenth century realists,” she warns us. According to Eliane, Sade’s debauchers have such a taste for evil that not a shadow of ambivalence exists in regard to their character. On the other hand, Machado de Assis’s sadist is a dissimulated man, who pretends to be a good person, although he exercises questionable habits in the silence of intimacy. “What one sees in this comparison is the historical process that leads to the exercise of perverse acts in private. Indeed, Machado de Assis is prodigal in scenes that reveal to us not only the Brazilian version of this private exercise, but also the very psychological interiorization of the practice of evil.” In this sense, for the professor, it is necessary to recall that Sade was a man of his time, undoubtedly, which does not stand in the way of his being modern and even post-modern, in so far as he is, and has been, known as such. “But he can also be an author ahead of his time and I also like to see him in this light. What I find most attractive about Sade is precisely this breaking away from the world that is reflected in his literature, in an attempt to awaken and bring into play hitherto unsuspected human virtualities. He resorts to imagination to ascend to the domain of the impossible.”

THE NIGHTMARE, DETAIL /JOHANN HEINRICH FÜSSLI“In Sade, all and any argument, no matter how rational it may be, ends up engulfed by fantasy, and in such a way that it is finally offered up to the reader as a hallucination. Nothing could be further away from Machado de Assis’s outstanding psychological realism,” she observes. The comparison, she adds, allows one to grasp the distance between literature that works with types, as is the case of the Marquis’s characters, and literature geared toward particular aspects of its characters, this being the characteristic of the great nineteenth century realists,” she warns us. According to Eliane, Sade’s debauchers have such a taste for evil that not a shadow of ambivalence exists in regard to their character. On the other hand, Machado de Assis’s sadist is a dissimulated man, who pretends to be a good person, although he exercises questionable habits in the silence of intimacy. “What one sees in this comparison is the historical process that leads to the exercise of perverse acts in private. Indeed, Machado de Assis is prodigal in scenes that reveal to us not only the Brazilian version of this private exercise, but also the very psychological interiorization of the practice of evil.” In this sense, for the professor, it is necessary to recall that Sade was a man of his time, undoubtedly, which does not stand in the way of his being modern and even post-modern, in so far as he is, and has been, known as such. “But he can also be an author ahead of his time and I also like to see him in this light. What I find most attractive about Sade is precisely this breaking away from the world that is reflected in his literature, in an attempt to awaken and bring into play hitherto unsuspected human virtualities. He resorts to imagination to ascend to the domain of the impossible.”

After all, in a universe in which God is allegedly dead, everything is allowed, and there is even room to think about what evil is. “Inverting Rousseau’s rationale about man’s natural kindness, Sade recognizes in evil the creative concept underlying all that exists. Evil becomes the Universe’s driving force, given that it is an essential category of the natural and of the human world. Although he stated that ‘the Universe would not survive for one second if all were virtue,’ the inverse is also true in regard to vice. It is a game of tension between creation and destruction that reveals the tragic sense of our existence,” notes Giannattasio. Likewise, in this philosophical scheme there is no room for Rousseau’s “social pact.” “The challenge, according to him, was to bring forth laws that took into account individuals and their role within society. The pact, on the contrary, proposed renouncing individual will for the general good. Sade disagrees with this and invokes the liberation of instincts. Whereas Rousseau wishes the destruction of natural forces, Sade defends them, stating that the only possible moral is that of each individual.” Or, in the words of the Marquis, in one of his letters: “It is not the opinions or the vices of the particular individual that harms the State; it is the habits of the public man that, alone, influence general administration. That a particular individual believes in God or not, that he honors a whore or gives her one hundred kicks in the belly, this conduct will not maintain nor shake the constitution of a State. If the corrupt politician triumphs, the other rots in prison.” In 1783, six years before the fall of the Bastille and the French Revolution, Sade already warned: “May the king correct the vices of government, may he reform the abuses, may he hang the ministers that deceive or rob him, instead of repressing the opinions and tastes of his subjects. These tastes and opinions shall not rock his throne, whereas the indignities of those who surround him shall topple him sooner or later,” a message that remains up-to-date.

“My body, in the morning, has a different disposition from that of my body at night. I may awaken as the most virtuous of men and go to bed as the most vicious of them,” wrote the nobleman. “Sade is materialism taken to the ultimate level, because, in the face of the needs of the body, how can one have a single reason that accounts for such multiplicity? Modernity is a time that invested and still invests all its efforts in the transformation of man into a rational animal. Sade is one of the expressions of the eighteenth century that best translate the futility of this effort, by opposing, to the image of the animal controlled by reason, the esthetic animal endowed with creative fury. Thus is Sade, a man ahead of modern times, yet deeply marked by it,” observes Giannattasio. Letters, after all, do not lie. Even those of the Marquis: “Enjoy, my friend, enjoy! And do not spend half your life trying to ruin the existence of others.”

Scientific article

MORAES, Eliane Robert. “Um vasto prazer, quieto e profundo”. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 23, n. 65, 2009.