After six years of construction, the Riachuelo is scheduled to be launched in December. The launch will take place in Itaguaí, in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro. The Riachuelo is the first of five submarines—four conventional and one nuclear-powered—that are being manufactured in Brazil as part of the Navy’s Submarine Development Program (PROSUB). In addition to patrolling and defending the so-called Blue Amazon, a maritime area of 4.5 million square kilometers rich in biodiversity and resources such as presalt oil reserves, the submarines are giving an important boost to the technological development of the Brazilian naval industry.

The amount invested in PROSUB is estimated at R$31.85 billion. The program includes the construction of an industrial complex in Itaguaí with two shipyards (one for construction and one for maintenance), a naval base, and the Manufacturing Unit for Metallic Structures. After the Riachuelo, the schedule calls for the completion of the conventional submarines Humaitá in 2020, Tonelero in 2021, and Angostura in 2022. The launch of the nuclear submarine, the SN-BR Álvaro Alberto, is scheduled for 2029 (see inset on page 79). With the completion of that submarine, Brazil intends to join the small group of six countries that possess nuclear submarine technology, made up of China, the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and India.

As they come online, the new S-BR Riachuelo-class conventional submarines will replace the current fleet of five Tupi-class vessels, says Admiral Bento Costa Lima Leite de Albuquerque Junior, the Navy’s Director-General of Nuclear and Technological Development (who was appointed the Minister of Mines and Energy a few weeks after being interviewed for this story.) The Tupi submarines were manufactured in the 1980s and 1990s. One was built in Germany and the others in Brazil, in a project carried out by Nuclebrás Heavy Equipment (NUCLEP) in partnership with the Naval Arsenal of Rio de Janeiro.

Modernizing the conventional fleet guarantees increased capabilities to monitor and defend Brazilian waters, as the new Riachuelo-class submarines have greater autonomy than the Tupi-class subs and can stay on mission for 70 days, as opposed to the 45-day limit of the current vessels. The nuclear sub, however, will raise that capacity to a new level. A conventional submarine is driven by an electric motor fueled by diesel fuel. Because the combustion of diesel fuel depends on oxygen, the vessel needs to emerge twice a day (on average) to capture oxygen from the air, or at least extend a snorkel tube to the surface. It also needs to refuel regularly with diesel. At such times, the vessel is exposed and becomes an easier target for attack during situations of conflict.

Nuclear-powered submarines are less vulnerable. Their source of energy is a nuclear reactor, which generates heat to vaporize water, enabling the use of this steam for turbines. Depending on the design of each submarine, the turbines can drive electric generators or the propeller shaft itself. In both cases, they produce all the energy necessary for life on board. “Because they have a virtually inexhaustible source of energy, they can theoretically be submerged for an unlimited amount of time,” Admiral Albuquerque explains. This means that submarine autonomy—understood as time away from port—is limited only by the physical and psychological resistance of the crews, and by food and water supplies. The United States Navy has defined this time limit as six months.

Another advantage of submarines with nuclear propulsion is their speed. While conventional subs move at an average speed of 6 knots (approximately 11 kilometers per hour), those with nuclear propulsion reach 35 knots—almost 65 kilometers per hour. As a result, they can quickly cover longer distances. “The availability of nuclear-powered submarines will significantly increase the operational dynamics of the fleet. The characteristics of these vessels, such as great mobility and stealth, guarantee significant deterrent capabilities in the defense of the Blue Amazon,” the admiral adds.

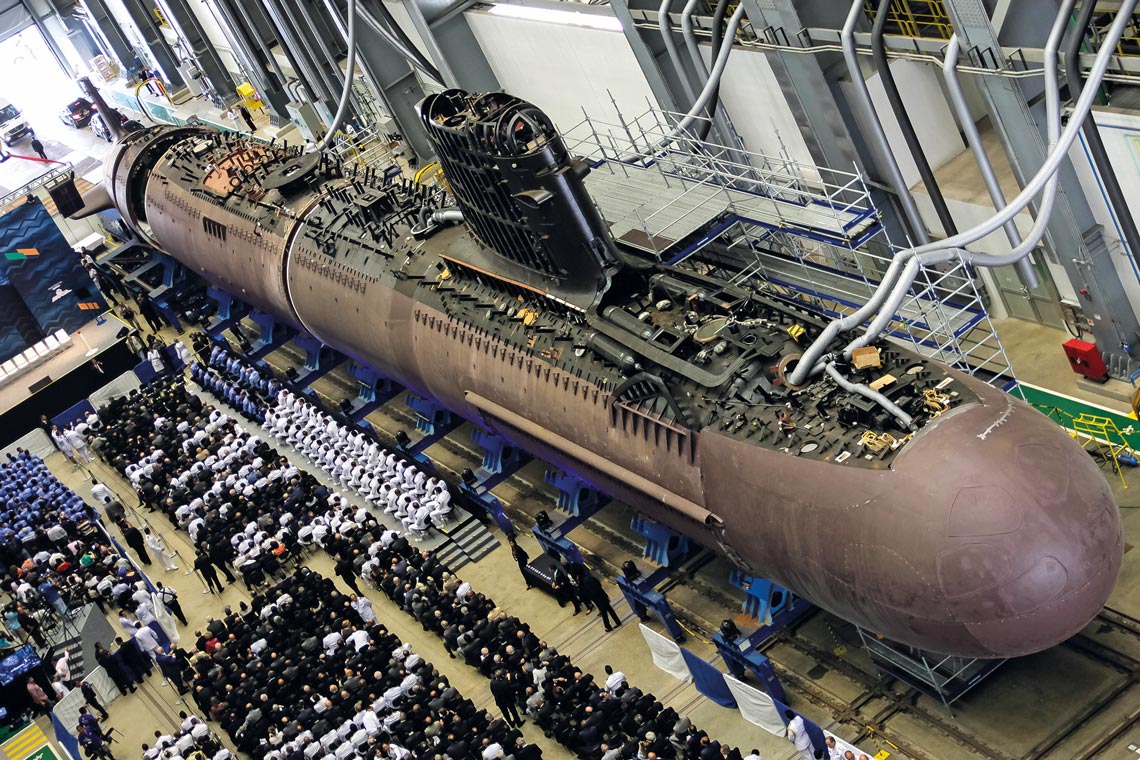

Brazilian Navy

Assembly of two sections of the Riachuelo, at the Itaguaí naval base, in RioBrazilian NavyTechnology transfer

PROSUB is the result of a cooperation agreement signed in 2008 between the governments of Brazil and France, with the participation of public and private companies under the coordination of the Brazilian Navy. The partnership stipulates that the French not only advise Brazilians on the construction of the submarines but also help to design the machines. France contributes nonnuclear technology to the projects and construction, and Naval Group, the company known until 2017 as Direction des Constructions Navales et Services (DCNS), is responsible for transferring the French expertise.

The Brazilian company involved in the project is the construction company Norberto Odebrecht (CNO), which has set up a special purpose entity (SPE) with DCNS, called Itaguaí Construções Navais (ICN), in which the Brazilian Navy holds a “golden share.” ICN is responsible for the construction of the shipyards, the naval base, and the submarines. The Manufacturing Unit for Metallic Structures is one of its operational arms. According to Admiral Albuquerque, the technological challenges of the project are being overcome with technology transfer in a number of areas, including industrial infrastructure, construction of the submarines, and control and combat systems. The nuclear propulsion system is not part of the agreement. The process of technology transfer involves the French supplying information and technical data on the submarines, as well as providing training courses, including specific training carried out in France and technical support.

Another action planned for PROSUB is the nationalization of the equipment and components used for the construction of both the infrastructure and the vessels. The program provides for the transfer of technology to selected Brazilian companies. To date, 52 Brazilian companies have already become involved with PROSUB, such as WEG in Santa Catarina, responsible for supplying the electric motors, the São Paulo company Adelco, a specialist in energy systems, and Newpower, which is in charge of developing suitable batteries for the submarines.

PROSUB is the result of a cooperation agreement signed between the governments of Brazil and France in 2008

One technology that the Navy considers critical to the project’s success is the submarines’ combat system, responsible for the control and management of the six torpedo tubes that equip the Riachuelo. This task became the responsibility of the Ezute Foundation, a private nonprofit institution created in 1997, which is accredited as a strategic defense company (EED) by the Ministry of Defense.

The process of nationalizing this system began in 2011, when nine professionals from the foundation were sent to France for training in systems engineering and integration; they also learned to develop Combat Management System (CMS) software. “Our engineers were responsible for creating the modules that allow the submarines to communicate with the tactical data link used by the Navy on its ships,” says Andrea Hemerly, director for the defense market at the Ezute Foundation.

Systems integration

Returning to Brazil in 2015, the team began to expand on the knowledge they had acquired, training new members for the project and supporting the Navy in the system integration for the Riachuelo-class submarines and in the preliminary design of the SN-BR combat system. “We’re confident that Brazil will achieve its goal of obtaining autonomy in submarine engineering and combat systems integration, as well as for the specifications, design, development, and systems integration for the first nuclear-powered submarine in the country,” Hemerly states.

Naval engineer Luis De Mattos, president of the Brazilian Society of Naval Engineering (SOBENA), says that Brazil has well-prepared technical personnel and an extensive industrial structure, which facilitates the absorption of technology. “What was missing was the opportunity. And that’s what PROSUB is creating,” he says. For Mattos, it was important for the Navy to establish clear objectives in the nationalization of the technology; the Riachuelo has 20% Brazilian-made content, and that value will increase with each new vessel. “PROSUB will allow Brazil to enter a select group of countries that are qualified to build their own submarines. In the future we’ll even be able to participate in international construction tenders,” he says.

The project to build a submarine with a nuclear reactor started in 1979 and will only be completed by the end of the next decade

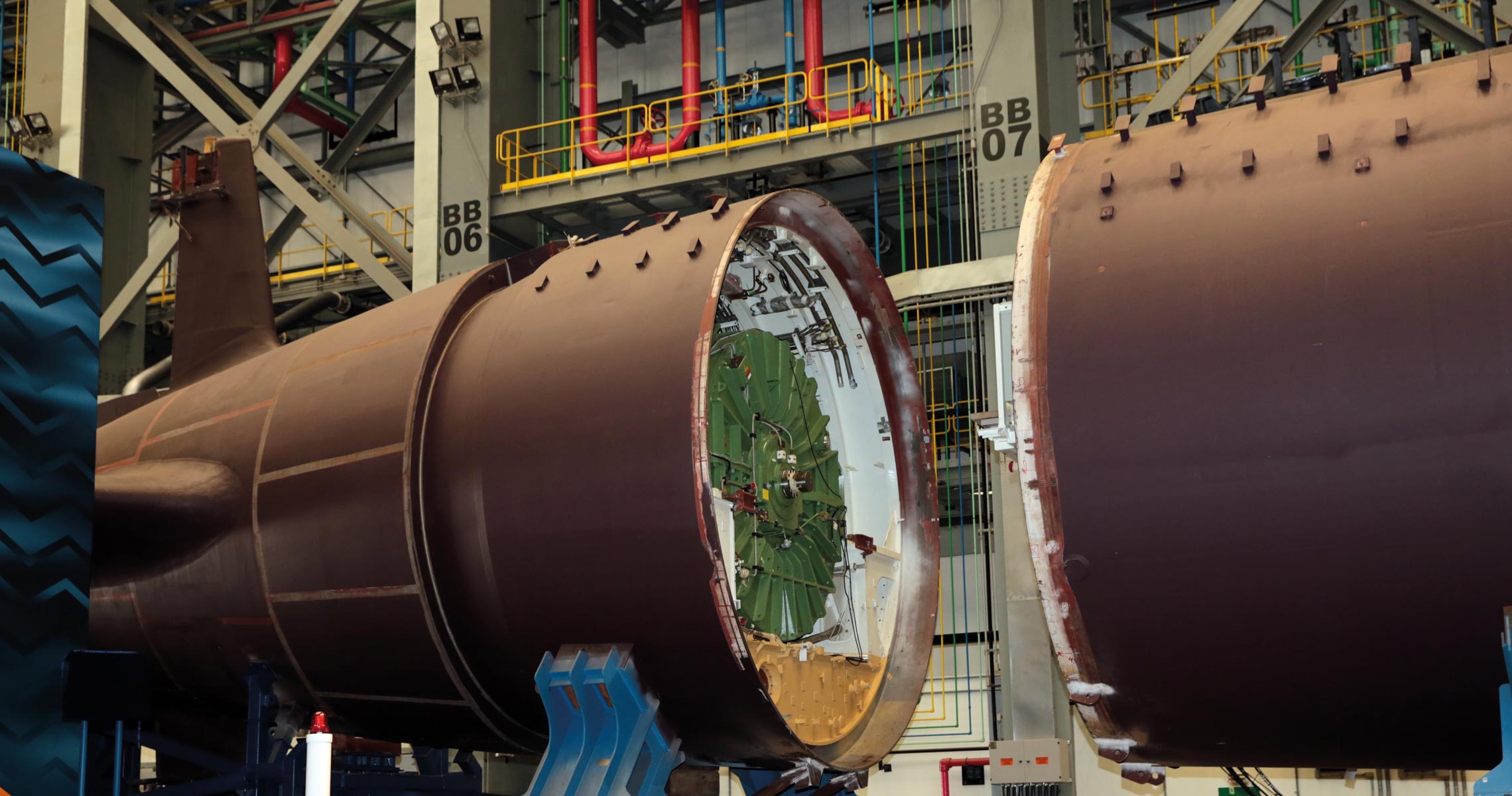

The Brazilian Navy via Air & Naval Defense

Cutaway view of nuclear submarine under construction in BrazilThe Brazilian Navy via Air & Naval DefenseThe construction of nuclear-powered submarines has been pursued by the government since 1979, when the Brazilian Navy Nuclear Program (PNMB) was created. Its purpose was to acquire the technical capacity to design, construct, operate, and maintain naval propulsion systems using nuclear reactors and to manage the nuclear fuel production cycle. The development of the SN-BR Álvaro Alberto submarine’s nuclear propulsion system is the exclusive responsibility of the Navy, which has already begun to deploy the Nuclear-Electric Energy Generation Laboratory (LABGENE) in Iperó, São Paulo. “LABGENE will enable the simulation of the reactor’s operation and its integrated electromechanical systems,” says Admiral Bento Costa Lima Leite de Albuquerque Junior, the Navy’s Director-General of Nuclear and Technological Development.

For the PNMB to achieve its goal, it is vital that the country master nuclear fuel cycle technology as well as the pressurized water reactors (PWR) used in nuclear power plants and submarine propulsion. “Among the fuel cycle stages, isotopic separation is the step that adds the most technological value and is the most complex. Therefore, the Navy prioritized uranium enrichment as the first stage to be mastered,” the Admiral says. Among the enrichment technologies, the most promising was ultracentrifugation. The first ultracentrifuges made in Brazil began operation in 1982.

With that technology, the country advanced in its development of new materials, electronic sensors, and new valves for operating with uranium hexafluoride (UF6, a compound used in uranium enrichment), which gave a boost to research centers in industry and at universities.

Despite these advances, construction of the nuclear submarine encountered difficulties, and the schedule had to be revised. In 2008, when Brazil and France signed the partnership that would

give rise to the Submarine Development Program, the plan was that a nuclear sub would be ready by 2021. The deadline is now 2029, a half a century after the start of the project.

Defense specialist Bernardo Wahl de Araújo Jorge, of the São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics Foundation, believes that in addition to the federal government’s budget constraints, the delay in completing the project has been due to difficulties with mastering the cycle of nuclear propulsion, which includes the process of producing the fuel.

“This is not a type of technology that is usually transferred from one country to another. The Army, Navy, and Air Force have developed technology programs looking for ways to enrich uranium. The Navy program prevailed by being the most efficient,” Jorge says. “If this submarine had been a priority for every government that came into office and if there had been no allocation restrictions, the delay would be unusual. As this hasn’t happened, the extensive amount of time that it’s taking to complete isn’t that extraordinary.”

Published in December 2018

Republish