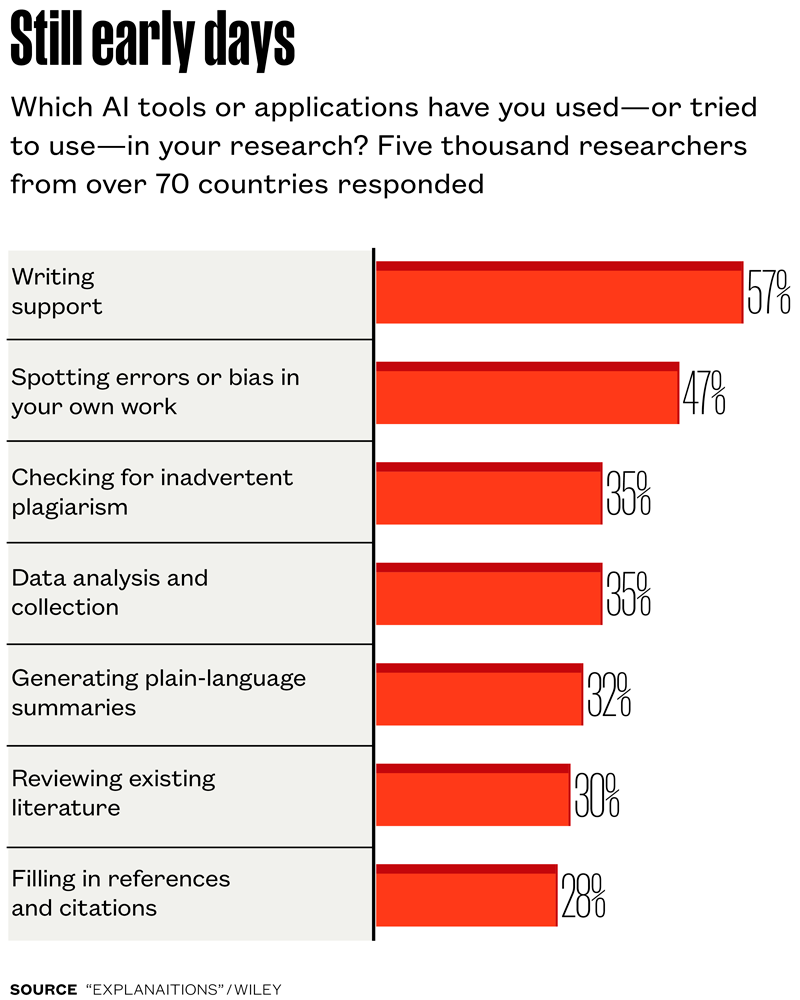

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools are just beginning to find their way into research—for now, their use is largely confined to writing-related tasks. But a new international survey by academic publisher Wiley suggests that’s about to change. Of nearly 5,000 researchers surveyed across more than 70 countries (including 143 from Brazil), the majority expect widespread adoption of generative AI in academia within just two years (see infographic below). “There’s a strong consensus that artificial intelligence is poised to reshape the entire research ecosystem,” said Josh Jarrett, vice president for AI at Wiley, in an interview with Nature.

The survey also asked researchers whether AI is already outperforming humans at certain day-to-day research tasks. Over half of respondents said yes—citing AI’s edge in tasks like identifying potential collaborators, summarizing papers into educational content, detecting plagiarism, filling out reference lists, and monitoring field-specific publication activity.

Still, most respondents agreed that humans are irreplaceable when it comes to higher-level tasks: spotting emerging research trends, choosing where to publish, selecting reviewers, managing administrative workflows, and seeking out grant opportunities. Despite rising enthusiasm, 81% of researchers voiced concerns about bias, data privacy, and the opaque training methods behind many AI systems. Nearly two-thirds also pointed to a lack of guidance and hands-on training as major obstacles to putting AI to fuller use in their work.

“In Brazil, many researchers still feel uncertain about the ethical paths forward when it comes to using generative AI,” says political scientist Rafael Sampaio of the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). “That’s why it’s crucial for institutions like the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education [CAPES] and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development [CNPq] to step in with formal guidance.” Sampaio coauthored a practical guide to the ethical and responsible use of AI in research, released in December in collaboration with business expert Ricardo Limongi, from the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), and digital education scholar Marcelo Sabbatini, from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE).

Sampaio uses AI tools in his own research. One go-to tool is Google’s NotebookLM, a platform that lets users ask research questions and get synthesized summaries based on curated materials. The app can “crawl” as many as 50 documents at once, including PDFs, audio, and video files—essentially serving as a multisource research assistant. For now, it’s free to use.

“I use it mostly for large-scale scans—for an initial triage or to help decide what’s worth a deeper read,” he explains. “It’s also great when I’m trying to track down a paper I’ve read before but can’t remember the title or author.” One neat feature is NotebookLM’s ability to generate podcast-style summaries with two virtual voices chatting about the documents—entirely generated by AI.

The guide Sampaio helped write catalogs several tools—including NotebookLM—that could be useful to researchers, but cautions that human oversight remains essential. AI should serve as an assistant, not an author. Limongi, one of the handbook’s coauthors, regularly uses LitMaps and Scite—two platforms designed to assist with literature reviews in selected fields. Users can upload a paper and get an interactive map of how that study connects to others, complete with clickable citations and reference links to build stronger arguments.

But Limongi notes that researchers need training to use these tools wisely. Uncritical use of AI, he cautions, can lead to deskilling—especially in areas like critical reading and the ability to articulate a coherent argument. “AI can assist,” Limongi says, “but it’s the researcher who designs and drives the study. We can’t reduce researchers’ role to just pushing buttons.” Science journals prohibit AI tools from being credited as authors—human researchers are always ultimately responsible for the scientific content—and for any text written with help from AI.

Claude.ai, a conversational AI chatbot and rival to ChatGPT, is gaining attention for its usefulness in drafting outlines and structuring scientific writing. At the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), Marcelo Sabbatini uses Claude regularly to sketch out initial drafts and refine both academic papers and public-facing science content. “I’ll ask for ways to frame a topic and then how best to develop the argument,” he says. “It gives me a structure to build on—fact-checking, digging deeper, and adding my own knowledge and perspective.”

Created by the San Francisco–based startup Anthropic, Claude topped the rankings in a May 2024 study published in Royal Society Open Science, which tested how accurately ten generative AI models—including ChatGPT and DeepSeek—could summarize scientific papers. But the overall picture wasn’t rosy. The study found that across 5,000 papers, the chatbots produced flawed or overstated conclusions in up to 73% of the summaries.

Created by the San Francisco–based startup Anthropic, Claude topped the rankings in a May 2024 study published in Royal Society Open Science, which tested how accurately ten generative AI models—including ChatGPT and DeepSeek—could summarize scientific papers. But the overall picture wasn’t rosy. The study found that across 5,000 papers, the chatbots produced flawed or overstated conclusions in up to 73% of the summaries.

Materials scientist Edgar Dutra Zanotto, of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), takes a multitool approach. He uses a suite of chatbots—ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Claude, Perplexity, and Gemini—for a wide range of research-related tasks. These tools help him polish English-language texts, run calculations (like figuring out the molar composition of glass based on molecular weights), and even suggest peer reviewers for the Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, where he’s an editor. “I look up the most influential researchers in the field I’m working on,” he explains.

Zanotto had prior experience with AI before the chatbot boom. At the Center for Research, Education, and Innovation in Vitreous Materials (CeRTEV)—a FAPESP-funded Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Center (RIDC)—he and his team trained a machine-learning algorithm using a massive dataset of 55,000 glass compositions. It’s one of the largest databases ever assembled in the field, capable of predicting novel glass structures that don’t yet exist. Before the advent of AI tools, designing a new glass formulation was a long, trial-and-error process. “Now, we can create a new glass in just a month,” Zanotto says. “It used to take years—and every new formulation came with a dissertation.”

AI is also proving useful for solving complex mathematical problems through tools like MathGPT. And increasingly, AI models are being used as coding companions. “Claude and Gemini are both popular right now for writing and debugging code,” Limongi notes.

Because these models are trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet, they often replicate the same biases found in those sources. And sometimes, they simply hallucinate—making up terms, names, and even references that don’t exist. To minimize those risks, Zanotto routinely tests the same prompt across multiple AI platforms and cross-checks the results to find the most reliable answer.

One clear strength of tools like ChatGPT is brainstorming—their ability to scan and combine information from vast data sets makes them powerful partners for early-stage ideation. Researchers can “chat” with the tool to get suggestions on how to approach a research topic or which paths to explore. But since the models are trained on preexisting content, their suggestions might not be entirely original—though they are also able to suggest novel variations of existing ideas.

Industrial engineer Roberto Antonio Martins, of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), has been testing out advanced AI tools like ChatGPT, Copilot, and DeepSeek, especially a recently added feature called “deep research.” This feature digs through both the web and academic databases, returning a synthesis of the topic along with a list of cited sources, Martins explains.

The process starts with the tool asking the user scoping questions—helping it generate a more precise and well-structured prompt before launching the search. Martins always starts by framing his research topic as a question. “This isn’t your typical keyword search,” he says. “When you ask a full question, you provide more context—and that usually means more relevant output.” Martins now lectures on the academic use of generative AI.

Researchers need training to understand the limits of AI

Perplexity, another chatbot gaining traction among researchers, is praised for its ability to fetch fresh, web-based content and provide clickable footnotes linking directly to sources. “I use these tools early on—when I’m gathering background information and forming initial hypotheses,” says Brazilian-born Cyntia Calixto, a professor of international business at Leeds University Business School in the UK. She’s been using AI tools in her research on CEO activism—how company leaders take public stances on controversial topics online. “It’s like having a research assistant to bounce ideas off as I dig deeper into the topic,” she explains.

When she needs to search for scientific papers, Calixto turns to SciSpace—a tool that not only finds research articles but also provides concise summaries of each one. Aydamari Faria-Jr., a biomedical scientist at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), recommends two other platforms: Answer This and Elicit. Both allow researchers to search across multiple scholarly databases like PubMed and Scopus. “They include filters that streamline the search process,” he explains, “and allow you to focus on specific study types—like randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis, or cross-sectional studies.” Faria-Jr. still pairs AI-powered searches with manual queries through academic databases, ensuring a comprehensive review of the topic he’s currently researching.

AI support in academic writing is also finding a role in upholding scientific integrity—particularly in assessing whether citations in a manuscript are sound and accurate. One tool, Scite, allows users to see the original context of a cited passage. It uses a deep learning model to assess whether the reference genuinely supports the citing statement—or if it actually contradicts it. Attorney and law professor Cristina Godoy, from the Ribeirão Preto School of Law (FDRP-USP), is a regular Scite user.

She recalls finding a Nature paper through Scite that added depth to one of her own research articles on AI. “Scite suggests articles that engage with your topic—and it links directly to the papers,” she explains. “You can even limit the search to specific journals.” Godoy also uses other AI tools for analyzing legal data. She is careful when it comes to generative AI. She never inputs excerpts from unpublished manuscripts—aware that these models can retain training data, and there’s no guarantee those ideas won’t surface in someone else’s output later on.

The story above was published with the title “Your new lab assistant?” in issue 352 of April/2025.

Republish

Created by the San Francisco–based startup Anthropic, Claude topped the rankings in a May 2024 study published in Royal Society Open Science, which tested how accurately ten generative AI models—including ChatGPT and DeepSeek—could summarize scientific papers. But the overall picture wasn’t rosy. The study found that across 5,000 papers, the chatbots produced flawed or overstated conclusions in up to 73% of the summaries.

Created by the San Francisco–based startup Anthropic, Claude topped the rankings in a May 2024 study published in Royal Society Open Science, which tested how accurately ten generative AI models—including ChatGPT and DeepSeek—could summarize scientific papers. But the overall picture wasn’t rosy. The study found that across 5,000 papers, the chatbots produced flawed or overstated conclusions in up to 73% of the summaries.