Just over a month after the 50-year anniversary of man’s first steps on the Moon, the aerospace industry is intensifying its efforts to return to Earth’s natural satellite. In the last few weeks, two private American companies—Blue Origin and Lockheed Martin—have presented designs for landing modules capable of carrying astronauts to the Moon and back from a new space station. On May 1, Boeing completed a full-scale test version of the station that NASA plans to launch into lunar orbit to serve as a base for future exploration of the Moon and possible interplanetary missions.

On Sunday July 20, 1969, two American astronauts were the first people to ever set foot on the dusty surface of the Moon after an intense race for military and technological power between the USA and the Soviet Union. Now, humankind’s return is once again linked to political interests and a desire by the countries involved to demonstrate their ability to achieve such a feat, as well as the pursuit of technological dominance. The official discourse, however, revolves around scientific objectives, plans to exploit natural resources, and economic interests involving mining, communications, and the transportation of both goods and people, among other possibilities.

Five decades after the first Moon landing, the USA remains the leading player in any potential return, although this time it is China trying to beat them to it. For the USA, the idea of putting people on the Moon and establishing a base there is associated with a sense of national pride, as well as President Donald Trump’s ambition to leave a grandiose mark of his time in the White House. Shortly after assuming the presidency in 2016, Trump demonstrated his desire to leave a space legacy similar to that left by John F. Kennedy, who in the early 1960s persuaded the country to put men on the Moon as a way of demonstrating the US’s technological superiority over the Soviet Union, which at the time was leading the space race. In April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first human being sent into space.

In 2017, having set a target of sending humans to Mars by the 2030s, Trump asked Robert Lightfoot Jr., then acting administrator of the agency, whether it would be possible to return to the Moon before the end of his first term in 2020. The exchange, which took place at the White House, was described by former Trump Administration communications aide Cliff Sims in the book Team of Vipers, published this year. Not long after, Trump reinstated the National Space Council (NSC), a presidential body that sets US space guidelines, and established a more modest target: to send astronauts to the Moon by 2028. In March this year, the plan was changed again, and the mission was brought forward to 2024—possibly in the hope that it will be achieved before the end of Trump’s potential second term.

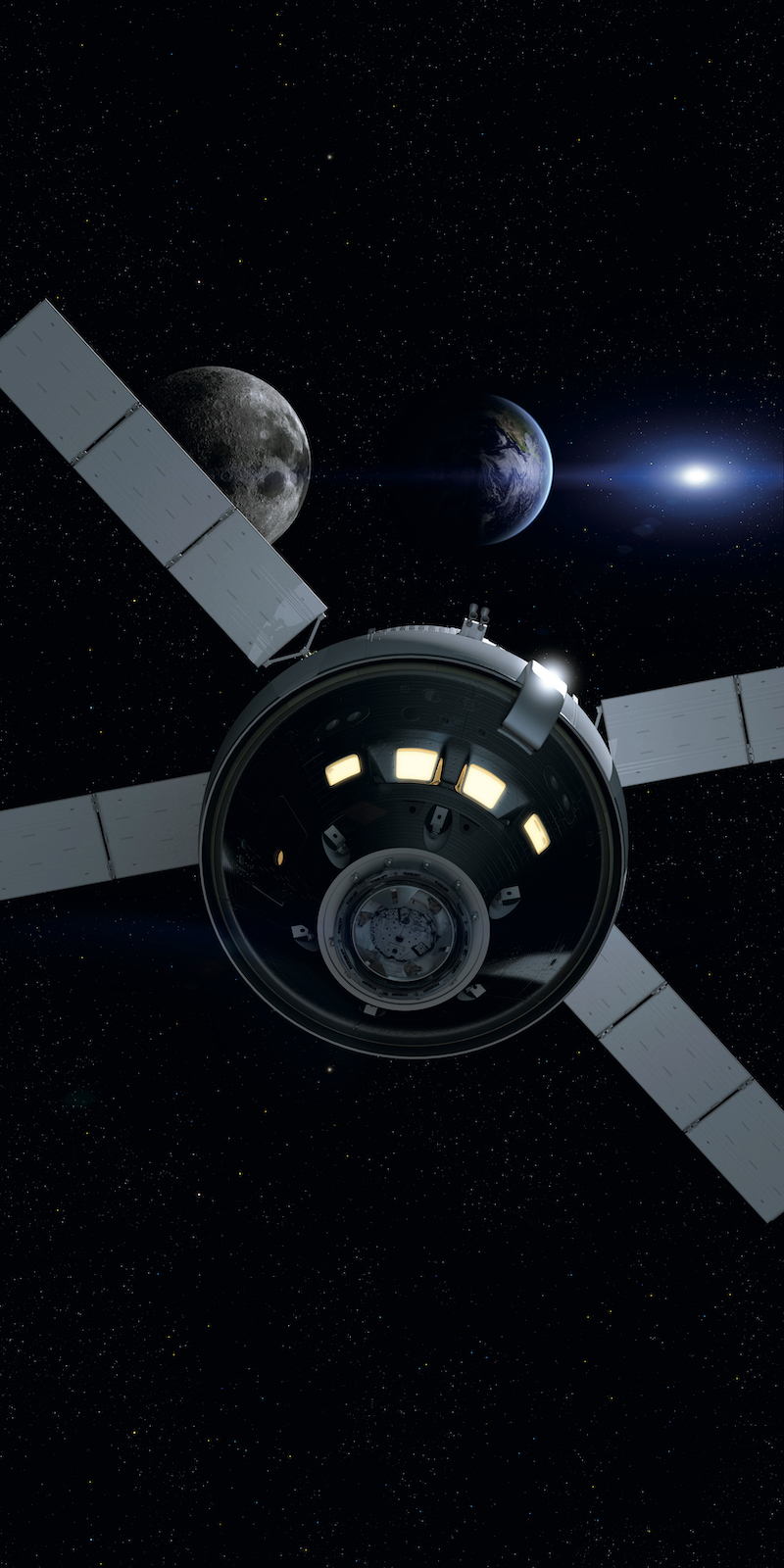

NASA

Artistic representation of the Orion capsule, designed to transport astronauts from Earth to lunar orbitNASAReturning to the Moon within such a short time frame, and with the aim of establishing a base of operations there, is a bold objective with a tight deadline. In six decades, approximately 130 manned and unmanned missions have visited Earth’s natural satellite, all from a select group of countries (USA, the Soviet Union, Japan, China, India, Europe, and Israel). The USA, however, is the only nation to have put people on the lunar surface and remains one of the few with the technology, knowledge, and money to repeat the accomplishment, although China, another economic superpower determined to demonstrate its technological power, has recently been investing heavily in the space sector.

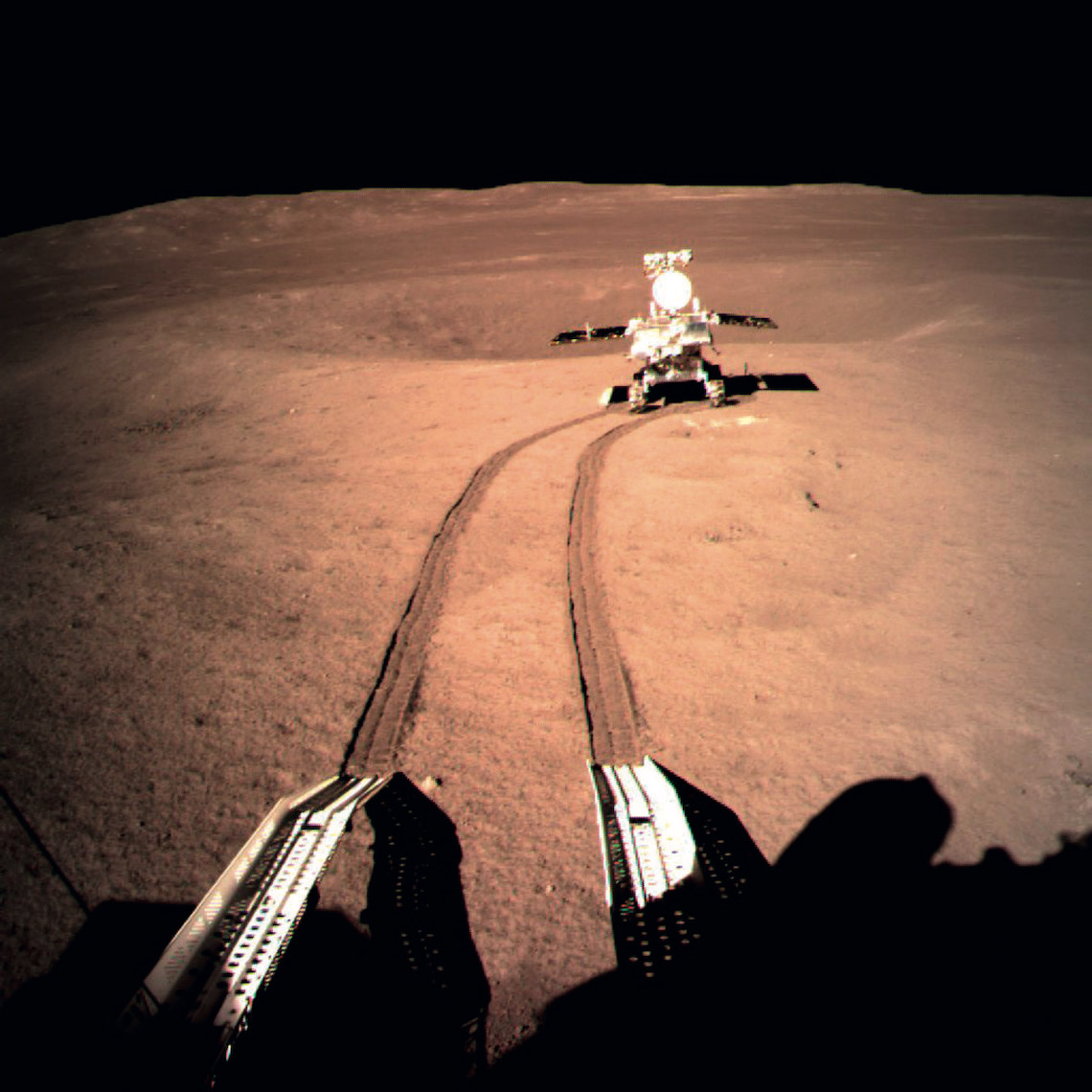

Over the last two decades, the Chinese space agency (CNSA) has launched two space stations into Earth’s orbit (Tiangong 1 and 2), taken 11 Chinese astronauts (known as taikonauts) into space, and sent nine unmanned missions to the Moon, seven of which successfully put probes onto its surface or into its orbit. The most recent was Chang’e 4, whose lander and rover successfully touched down on the far side of the Moon in January this year. “Today, China is the only country with a strong justification for putting humans on the moon,” says mechanical engineer José Bezerra Pessoa Filho, a retired researcher from the Brazilian Aeronautics and Space Institute (IAE) and a specialist in the history and politics of the space race. “One of its taikonauts setting foot there will establish the country as a real global power.”

America’s new mission to the Moon was given an official name in May: Artemis, after the Greek goddess of nature and the hunt, twin sister of the god Apollo, whose name was given to NASA’s manned program in the 1960s. To put the Artemis program into practice, NASA and the companies it collaborates with will have to step up and invest heavily. They must first complete development of the Space Launch System (SLS), a super-rocket capable of reaching the Moon, which if all goes to plan, should be ready for its first launch next year. Tests are also required for the Orion capsule, which will transport the astronauts from Earth to the Gateway, a space station to be built in lunar orbit. This station, which is designed to enable multiple lunar landings in reusable modules still under development, is expected to be partially ready by 2024. In the Apollo missions, the spacecraft were only usable once and then returned to Earth.

“The president challenged NASA to land the first American woman as well as an American man on the South Pole of the Moon by 2024, then to establish a sustained presence on and around the Moon by 2028,” William Gerstenmaier, Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations at NASA, told Pesquisa FAPESP. In an email interview, he confirmed that while efforts will be led by the United States, a number of international partners will play a significant role. The European Space Agency (ESA), for example, is providing the energy and propulsion systems for the Orion capsules, and Canada is set to supply some of the robotics for the Gateway space station. “We have created a set of international interoperability standards that will allow any nation to participate in our plans,” explained Gerstenmaier.

NASA

Artistic representation of the SLS rocket currently under developmentNASAWhy go back?

In December 1972, Apollo 17 astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt were the last humans to set foot on the Moon. Having proven the USA’s dominance in space, the Apollo program, which took up a substantial part of the country’s national budget, was closed. No person has been to the Moon since. The allure of returning, however, has never diminished. NASA began investing in (cheaper) unmanned missions to other destinations in the solar system, and in 2004, George W. Bush asked the agency for an exploration plan that would include humans returning to the Moon by 2020 and eventually, a manned mission to Mars. Initial estimates indicated that the program, known as Constellation, would cost US$230 billion (2004 values) over 10 years. Despite early progress, Barack Obama closed the program in 2009 due to the high costs, but allowed the agency to continue working on the SLS rocket and the Orion capsule.

For space enthusiasts, the reasons to return to the Moon are numerous. One is that we still have a lot to learn before targeting more challenging destinations like Mars. Little is known, for example, about what happens to the human body after long periods in a low-gravity environment and long-term exposure to cosmic radiation. Even astronauts who spent a long time in space—at Russia’s Mir space station or at the International Space Station (ISS), for example—have never been exposed to low gravity or radiation for long enough to simulate life on the Moon or a trip to Mars.

The Moon’s proximity also makes it an attractive location for field tests. Its distance from the Earth varies from 363,000 to 405,000 kilometers, which can be covered in three days. Mars, at its closest, is 130 times farther, at 55 million kilometers away—astronauts would have to travel for at least nine months to get there. “The Moon is where together, we will design, develop, and test the systems that will ultimately help us send astronauts to the red planet,” says Gerstenmaier.

Going back to the Moon does not require any new and innovative technology, according to Oswaldo Loureda, founder and CEO of Acrux Aerospace Technologies, a Brazilian startup that specializes in the production of small rockets, drones, and microsatellite structures. Since the Apollo program, we have known how to get there. “The current challenge is the schedule and the costs,” he says. Just as important as building a powerful enough rocket is testing the new capsules to ensure they can safely carry humans.

Development of both the SLS rocket and the Orion capsule needs to be completed before humankind can return to the Moon

Space agencies, experts, and enthusiasts cite many other scientific interests that justify a return to the Moon and the establishment of a human settlement there. One is to study its geology and investigate the theory that it was formed around 4.5 billion years ago from the remnants of a huge impact between Earth and a Mars-sized ancient planet called Theia. The absence of an atmosphere (there is no wind or rain on the Moon) means the lunar landscape is perfectly preserved and could help us to learn more about the evolution of our solar system. Lunar craters, for example, are the scars of an intense meteor bombardment that occurred 4 billion years ago—on Earth, these traces have long been erased by weathering and the movement of tectonic plates.

“I see the Moon as a gateway to the exploration of deep space,” says space engineer Antônio de Almeida Prado, a specialist in orbits and space trajectories from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Gravity on the Moon is six times lower than on Earth, meaning that larger, heavier spacecraft can launch from the lunar surface or space stations in its orbit than from Earth, facilitating longer missions to farther distances.

There are also economic incentives behind returning to and potentially colonizing the Moon. Studies suggest that it may be home to a significant volume of rare minerals. There may also be large concentrations of helium 3, a version of the chemical element helium that is rarely found on Earth and could in principle allow thermonuclear reactions to occur, producing large amounts of energy. The frozen water in the craters near the South pole could provide oxygen for astronauts and hydrogen that could be used as rocket fuel. Private companies in the USA, Europe, and countries like China are enticed by the idea of exploiting these resources in a potential mineralogical race that could spawn a trillion-dollar industry. The cost-effectiveness, however, depends on how cheap space travel can become through the use of reusable shuttles and rockets.

A lunar colony could even serve as a sociological and anthropological experiment, according to Brazilian engineer and entrepreneur Sidney Nakahodo, cofounder and CEO of the New York Space Alliance, a company that fosters the development of space startups. Also a professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), Nakahodo believes that humans living in settlements outside Earth could end up developing new social and economic structures governed by an as yet undefined legal framework.

NASA

The Yutu-2 robotic rover, photographed by the Chinese probe Chang’e 4, which landed on the far side of the Moon in JanuaryNASAThe Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prevents its signatories from claiming possession of territories on other celestial bodies. It also states that space exploration must benefit humankind and that all states are free to explore space without discrimination of any kind. In the absence of international consensus, Nakahodo predicts that exploration and occupation of the Moon will be similar to the process that occurred in Antarctica. In a document signed in 1959, 12 countries that were at the time claiming possession of areas in Antarctica suspended their claims for an indefinite period. The text states that other countries wishing to participate in discussions regarding the continent must demonstrate that they conduct significant scientific research in the region. “If a similar treaty is drawn up for the Moon, Brazil will only have a voice if it can prove itself capable of carrying out important research there,” says Nakahodo.

For now, the Brazilian government has no plans to study the Moon, but there is a private project, known as Garatéa-L, which intends to send a nanosatellite into lunar orbit. “Putting equipment near the Moon could allow the country to enter a restricted club,” says Carlos Augusto Teixeira de Moura, president of the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB). “It would be a demonstration of our technical capacity that could give us a voice in future international talks.”

Before these plans become reality, however, humankind needs to show that it can actually return to the Moon, something that will not be as easy as Trump would like. On May 16, the US House of Representatives approved a bill adding US$1 billion to NASA’s budget for the 2020 fiscal year, taking the total to roughly US$23 billion, which represents 0.5% of all US federal spending—far less than the 4% allocated at the height of the Apollo program. Even with the extra funding, the agency is not receiving enough to return to the moon by 2024. Some experts estimate that the budget needs to increase by US$5–8 billion per year in order to reach that target.

The amount approved in May is almost 40% lower than that requested by Trump. Many congressional Democrats had reservations about the bill. “I am going to reserve judgment on the overall Moon landing plan until Congress is provided with more concrete information on the proposed lunar initiative,” said Democrat congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson from Texas, who chairs the House Science Committee. According to an article published on May 16 in the journal SpaceNews, which specializes in space industry politics and business, Johnson is keen to know more about the total cost and technical details of the mission, which have not yet been disclosed.

Republish