Geologists have long known that 20,000 years ago, the sea off the coast of the city of Recife, Pernambuco, was approximately 125 meters (m) below its current level. At the time, the area that would later become Boa Viagem beach, one of the best-known beaches in the state capital, was occupied by forests. There may even have been rivers and waterfalls falling from the heights of what is now the continental shelf — the boundary between the shallowest and deepest areas of the ocean.

Sea levels have risen significantly between then and now. According to Antonio Vicente Ferreira Junior, a geographer from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), the average sea level in Recife and the surrounding coastal areas may have reached 3 m above today’s average level between 4,700 and 4,100 years ago. That would be high enough for the waves to inundate the mouth of the Capibaribe River, the seafront avenues, and the centers of coastal cities in the greater metropolitan region.

Studies on the topic — like the one published in Ocean and Coastal Research by Ferreira Junior in April — describe, detail, and correct old information using newer, more precise techniques. They also serve to indicate the areas most vulnerable to rising sea levels, which is expected to intensify over the coming decades due to climate change. The rising average global temperature is warming the ocean and increasing its volume; it is also melting glaciers on land, another contributing factor to greater sea volumes.

Helenice Vital / UFRNEnxu Queimado Beach in São Miguel do Gostoso, Rio Grande do Norte, with exposed beachrocks that show variations in average sea level over the last 10,000 yearsHelenice Vital / UFRN

“In the 1980s, we didn’t have geodetic GPS, which we use today to measure a location’s altitude with great precision,” says geologist José Maria Landim Domingues of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). Domingues was doing his PhD when he participated in a team led by geologists Kenitiro Suguio (1937–2021) of the University of São Paulo (USP) and Louis Martin of the Office of Scientific and Technical Research Overseas (ORSTOM) in France, now the Research Institute for Development (IRD).

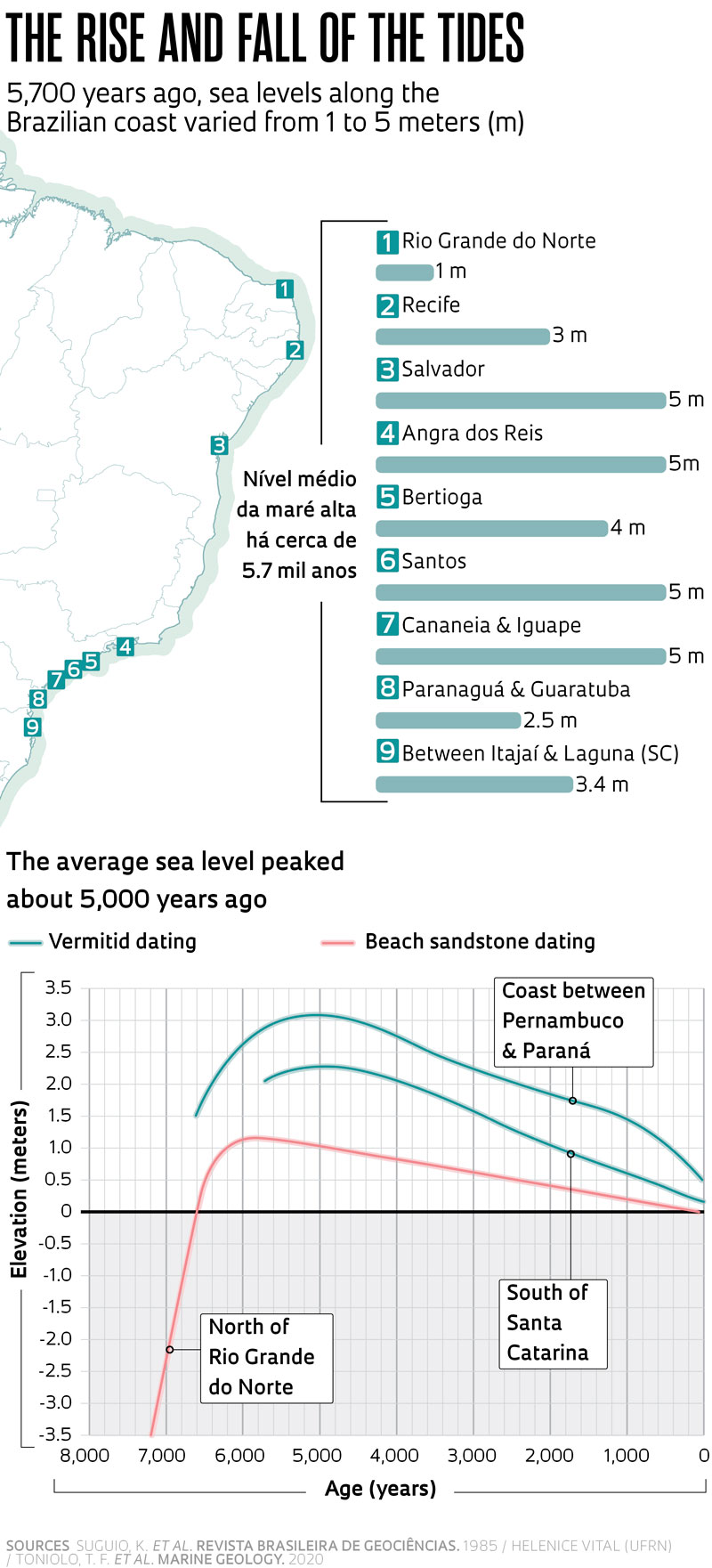

Together with other geologists, the trio collected and analyzed some 700 rock samples and marine organism remains along the coast from northern Alagoas to southern Santa Catarina. Their work, published in Revista Brasileira de Geociências in 1985, revealed local and regional variations in the average sea level — in the Northeast, it may have reached 5 m above current levels around 5,700 years ago, while in the South, it would not have exceeded it by more than 3 m.

Little by little, a concept was formed: “A few years ago, there was talk of a uniform global change in sea level, but today we know that every region has its own distinct characteristics due to the geology and terrain,” explains Helenice Vital, a geologist from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Her team has been monitoring sea level fluctuations off the coast of Rio Grande do Norte for 20 years (see infographic), publishing their findings in specialized journals, such as Marine Geology, since 2006.

Defined as the average altitude of the ocean surface, the sea level in Brazil was first recorded in Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, in 1781 by the Portuguese astronomer Bento Sanches Dorta (1739–1794), and it was then measured regularly from 1831 onwards. The rise and fall of the sea reflect the gravitational forces of the Moon and the Sun, the deformations of ocean surfaces, the melting or formation of glaciers, and changes in the Earth’s axis, which make the sea sway as if it were in a bowl suspended in the air.

Rocks and shells

Recorded on coastal cliffs, fluctuations in the average sea level can be measured in several ways. Vital and Ferreira’s groups examined variations over the past 10,000 years — the geological period known as the Holocene — using sedimentary rock known as beachrock, which can indicate sea levels in the distant past. They only form on the coastline between land and sea, when river water meets sea water and dissolves the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) from marine organisms, cementing the sediment. According to Landim, this cementation was first recorded by Portuguese entrepreneur and historian Gabriel Soares de Sousa (1540–1591) in Tratado descritivo do Brasil (Descriptive treaty of Brazil; 1587), although he attributed the formation of what he called “beach pebbles” to sand freezing due to contact “with the coldness of the sea water.” Microscopic analysis and carbon dating of a form of CaCO3 from shells embedded in the beachrock indicate when the sediment layers were formed — information used to determine sea level changes at the location.

In early June, geologist Rodolfo José Angulo and his team from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), together with colleagues from abroad, visited the beaches of Laguna, Santa Catarina, in search of another indicator of sea level changes: sea snails known as vermitids. Determining the age of one of the forms of carbon in the shell of these mollusks tells us when the organism settled on the rocks near the low tide line.

“Sometimes we found vermitids on hills, indicating that the sea level was once higher there,” he notes. His plan is to discover how the sea rose and fell on the Santa Catarina coastline in a more recent time period of the last 300 years, combining information from mollusk shells and two devices that monitor fluctuations in the sea: tide gauges (Brazil has a network of around 330 devices along its coast) and satellites, such as the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-6.

The UFPR group has used beachrock, vermitids, and coral to show that between 5,000 and 6,000 years ago, the sea level was almost 3 m higher than it is today in the Abrolhos archipelago and 4.5 m higher in the Rocas Atoll, both off the Brazilian coast. The results were described in articles published in Marine Geology in May and August 2022.

Antonio Vicente Ferreira Junior / UFPEMuro Alto Beach in Ipojuca, Pernambuco, where a strip of shallow sandstone extends for 4.7 kmAntonio Vicente Ferreira Junior / UFPE

Together, these studies shed light on the transformations of the Brazilian coast. “120,000 years ago, the continental shelf of Pernambuco was part of the continent,” says Ferreira. Landim continues to paint the picture: “20,000 years ago, the bays of Todos os Santos [Bahia] and Guanabara [Rio de Janeiro] did not exist, nor did Lagoa dos Patos lagoon [Rio Grande do Sul]. Everything was covered in vegetation — until the sea rose and flooded everything.”

After falling, rising, and then stabilizing, sea levels are clearly on the rise again all over the world. “It is unquestionable that the sea level has been rising in recent decades,” says Angulo.

According to NASA, the global average sea level has risen by around 9.4 centimeters (cm) since 1993. It rose by 0.7 cm in 2022 and 2023 alone due to global warming and the intense El Niño. “In theory, we should be entering a geological period of cooling, with the water level falling,” says Vital. “But that’s not what we’re seeing.”

NASA’s Sea Level website projects a rise of 10 cm by 2030 in Belém, Recife, Rio de Janeiro, and Cananéia, on the coast of São Paulo. In an article published in Natural Hazards in March, a group from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) also predicted that the sea around Fiscal Island, bordering the historic city center of Rio de Janeiro, will rise by 70 cm by 2100. Such an increase would lead to the loss of the remaining mangrove areas, increasing marine floods and negatively impacting tourist attractions in the city. The prospect of intense damage has led coastal municipalities in Brazil to plan preventive measures against rising sea levels (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 238).

“To define the areas most vulnerable to rising sea levels, we need to create precise maps on a centimeter scale,” says Landim. Using a remote laser technology called Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging), he found that in the municipality of Belmonte, Bahia, the most sensitive areas are occupied by few residents. “Narrow urban beaches squeezed between roads and the sea tend to disappear unless sand is added to them, an expensive process” (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 338).

There is a very real possibility that the oceans will advance over islands and the continent. In June, as a result of rising sea levels, the government of Panama, Central America, asked one thousand residents of Gardi Sugdub Island, one of 50 occupied by the Guna indigenous people, to move to a newly built city of prefabricated houses on the mainland. According to a CNN report, the new homes have no access to water or health services. Change, however, is necessary. “Within 40 to 80 years — depending on the height of the islands and rates of sea level rise — most, if not all of the inhabited islands, will literally be underwater,” Steven Paton, director of the Smithsonian Institution’s physical monitoring program in Panama, warned CNN.

The story above was published with the title “The marks of ancient tides” in issue 342 of august/2024.

Scientific articles

ANGULO, R. J. et al. Mid-to Late Holocene sealevel changes at Abrolhos archipelago and Bank, southwestern Atlantic, Brazil. Marine Geology. Vol. 450, 106841. Aug. 2022.

ANGULO, R. J. et al. Paleo-sea levels, Late-Holocene evolution, and a new interpretation of the boulders at the Rocas Atoll, southwestern Equatorial Atlantic. Marine Geology. Vol. 447, 106780. May 2022.

CALDAS, L. H. de O. et al. Holocene sea level history: Evidence from coastal sediments of the northern Rio Grande do Norte coast, NE Brazil. Marine Geology. Vol. 228, no. 1–4, pp. 39–53. Apr. 30, 2006.

FERREIRA JÚNIOR, A. V. et al. Beachrocks of the northeast of Brazil: Local effects of sea level fluctuations in a far-field during in Holocene. Ocean and Coastal Research. 2024. Vol. 72, e24022. Apr. 12, 2024.

SUGUIO, K. et al. Flutuações do nível relativo do mar durante o quaternário superior ao longo do litoral brasileiro e suas implicações na sedimentação costeira. Revista Brasileira de Geociências. Vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 273–86. Aug. 1985.

TOSTE, R. et al. Dynamically downscaled coastal flooding in Brazil’s Guanabara Bay under a future climate change scenario. Natural Hazards. Online. Mar. 26, 2024.

Republish