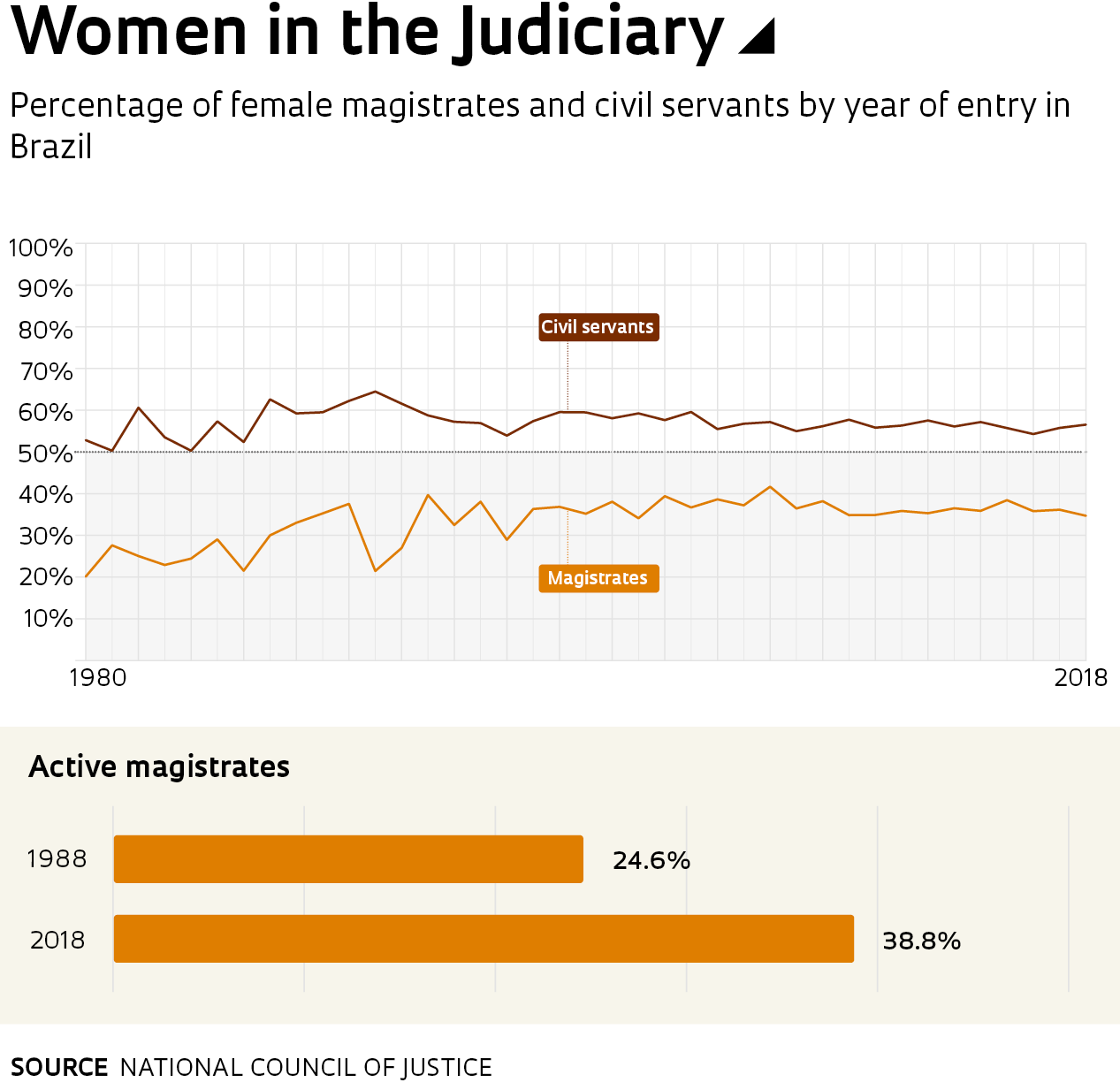

Women represent half of the 1.2 million registered members of the Brazilian Bar Association (OAB), but they are outnumbered in leadership positions in the public and private law sectors, compared to men. In courts, a survey by the National Council of Justice (CNJ) shows that, in the last 10 years, women magistrates have held no more than 30% of the positions of president, vice president, internal affairs officer, or ombudsperson.

“The percentage of women in various legal careers is about 40%, but they do not rise in the ranks at the same rate as men. As you look higher up the career ladder, the participation of women declines,” claims sociologist Maria da Glória Bonelli, of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar). A CNJ study, conducted with data from 68 out of the 90 courts in Brazil, found that women represent 38% of the judiciary. In segments such as State Military Justice, they represent 3.7%. In terms of leadership positions, the Labor Court is where their numbers have been highest in the last decade, ranging from 33% to 49%. On the other hand, there is no record of women in leadership positions in State Military Justice in the same period.

Bonelli—who recently finished a research paper called “Descentrando a docência do direito: Gênero e diferença no ensino jurídico no Brasil” [Shifting the teaching of law: Gender and difference in legal education in Brazil]—believes there are many hypotheses for the low numbers of women in leadership positions in Brazil. One of them concerns the fact that they need to take on the roles related to the care, management, and organization of family life. “Men, on the other hand, have historically occupied positions of high visibility in the legal professions, be it on examination boards, at conferences, or with professional associations,” she points out. According to the Summary of Social Indicators, released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in November, about 20% of Brazilian women currently don’t seek jobs because they need to take care of household chores, children, or family members. That number is nine times higher than that of men.

Structural issues discourage female students from participating in the classroom

Judiciary careers begin in small counties. As a professional’s career progresses, he/she is transferred to larger cities. “This dynamic can hinder the career progression of women judges who have children, for example. Moving to another city requires looking for new schools and rethinking their support system,” says Bonelli. The sociologist presents another hypothesis that may explain the lower number of women in leadership positions: the Brazilian legislation itself, which allows them to retire five years earlier than men. “This means that some women choose to retire before reaching the highest positions,” she says.

Despite their minority status in leadership positions, the CNJ found that the presence of women in the judiciary has been increasing for the past 30 years. It went from 24.6% in 1988 to 38.8% in 2018—and before 1980, their numbers were insigificant. Today, Labor Courts and State Courts are the areas with the highest percentages of women working in the judiciary: 50.5% and 37.4%, respectively.

Regarding administrative positions, the CNJ survey showed that women represented 56.6% of the total number of civil servants in the judiciary in the last 10 years, having occupied 56.8% of the positions of trust and commissioned positions and 54.7% of leadership roles during the period that was analyzed. “This type of job isn’t male-dominated, and the participation of women is significant. These are administrative activities, with routine assignments that follow orders from the judiciary. In other words, they are jobs with less autonomy, expertise, and compensation compared to male-dominated careers, such as that of the judiciary,” Bonelli observes.

The tendency of early generations of women who joined the judiciary was to mirror men, so until recently many of them used the term “juiz” [the Portuguese masculine word for “judge”] instead of “juiza” [the feminine word for “judge”] to refer to themselves, Bonelli notes. “Today, the term ‘juíza‘ is often used, but the profession has not yet managed to break away from male logic,” she says, referring to the inauguration of Attorney General of the Republic Raquel Dodge, in 2017. “In photos of the event, we see Dodge and Supreme Court Justices (STF) Rosa Weber and Carmen Lucia dressed in black, wearing pearl necklaces, presenting an image of supposed neutrality and as part of a gender erasure dynamic.”

The issue is also present in the classroom. In 2015, Sheila Neder Cerezetti, from the Department of Commercial Law at the University of São Paulo Law School (FD-USP), was approached by a group of female students who reported not feeling comfortable participating in class. Whenever they made contributions, they noticed that their arguments had little repercussion. “These students wanted to investigate whether their feelings were individual or related to structural issues at the university,” recalls Neder Cerezetti, who had already noticed the prevalence of contributions from men and also the fact that girls usually waited until the end of class in order to ask questions in private.

A study was developed from the work of 23 female researchers and students, from both undergraduate and graduate programs, under the coordination of Neder Cerezetti: “Interações de gênero nas salas de aula da Faculdade de Direito na USP: Um currículo oculto?” [Gender interactions in USP Law School classrooms: A hidden curriculum?]. It analyzed classroom dynamics, looking to understand how gender impacts the teaching-learning process within the Largo São Francisco campus. Lívia Gil Guimarães, a PhD student at the institution and a coordinator of the Grupo de Pesquisa e Estudos sobre Inclusão na Academia (Research and Study Group on Academic Inclusion) (GPEIA), explains that project results are in line with the findings of papers written abroad—such as the study “Becoming gentlemen: Women, law school and institutional change.” Developed by researchers from US institutions, such as the University of Pennsylvania and Colgate University, the study found that, at the beginning of their studies, female law students are self-confident and eager to practice law in the field of public law—but that eagerness fades before graduation.

By observing students from undergraduate classes and interviewing individual students, the FD-USP research identified structural issues that discourage female student participation in the classroom. Among them are the facts that all rooms are named after male professors and there are no female authors in the curriculum. It was also found that the number of women in undergraduate law programs is higher in the early years.

The study also analyzed the relationship between students and teachers at different class times. “We saw that students perceived male professors as complex beings, able to be both strict and fun, while female professors are usually labeled into flat categories: they were either regarded as strict or maternal,” highlights Cecilia Barreto de Almeida, a master’s student at the institution and one of the coordinators of GPEIA. Another frequent situation, seen mainly in night classes, involves clashes between older students, who usually pursue law as a second degree, and female professors. “Many of them behave in the classroom as if they were authorities of knowledge in relation to the female professors—which is not always the case, since they may have a degree, but no legal training,” says Neder Cerezetti.

Based on these observations, the study defends the existence of a “hidden curriculum” at the university, that is, a teaching-learning dynamic that prioritizes and encourages the participation of men to the detriment of women. “We noted there is an ‘invisibilization’ of the female gender and a naturalization of the male gender, either because they participate more frequently or due to the examples and bibliography taught, which tends to prioritize male authors,” Guimarães comments.

Neder Cerezetti believes reality needs to be rethought. “The classroom is the space where future professionals are trained, and unequal relationships impact the development of their legal careers,” she declares. According to Neder Cerezetti, the first steps to this transformation effort were taken shortly after the study results were published, when other professors began to pay attention to the participation rate of men and women in the classroom. This was the case for Nina Beatriz Stocco Ranieri—a professor at the institution for 17 years. “I had noticed that girls were quieter, but I attributed it to the large number of students. The study removed a veil, showing me how necessary it is to find ways to give their voice more strength, prioritizing their contributions and taking private questions to the whole class,” says Ranieri. Another initiative involves the adoption of more women authors into the curriculum, in addition to using examples of women jurists and lawyers who have reached high-ranking positions.

Institutionally, another change was the inauguration of the first room named after a woman, Ada Pellegrini Grinover (1933–2017), a proceduralist of Italian origin who was a full professor at the institution until 2003. Grinover was the first woman to defend her PhD in law at USP and the first female professor of procedural law; she was also associate dean of undergraduate programs at the university. “The school was created in 1827 and to this day all of its rooms have been named after men, which helps perpetuate a male-centric culture,” says Ranieri, highlighting the need to change physical environments so as to amplify the presence of women.

Much like FD-USP, the Olinda Law School—nowadays called the Recife Law School (FDR)—at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), is among the oldest in the country. At the FDR, there are more women teaching undergraduate students than graduate students, shares Luciana Grassano Melo—the first woman to run the institution, between 2007 and 2015. “In both cases, women are a minority, but their number decreases a lot in graduate programs. The participation of women on examination boards and in conferences is also limited,” she notes. Melo explains that, in order to expand the number of female professors in master’s and PhD programs this year, six professors who taught in undergraduate programs were incorporated into graduate programs. “In addition, we started offering a course on feminism for graduate students,” shares Melo, who is also a professor of financial and tax law.

Law graduates facing criminal charges involving violence against women can no longer apply to the OAB

One of 26 women in the faculty of FD-USP, which consists of 150 professors in total, Ranieri advocates the need for studies that allow understanding the reasons for the low number of women in teaching. In this regard, the university intends to develop comparative research with French and North American institutions, starting next year. “In Brazil, half of all law school undergraduates are women, who in turn represent 40% of undergraduate-level professors and 20% of professors in graduate programs,” says Bonelli, of UFSCar.

Also, as a result of the USP research paper, an ombudsman office was created at FD-USP for complaints related to gender issues, as well as a commission to combat prejudice against women. The rules for public competitions for new teaching openings have been changed, so that a pregnant candidate may request to defer the position for one year. “The study has resonated with other educational institutions and private law firms, who come to us in order to understand how they can transform their work environments,” says Neder Cerezetti.

In order to ascertain the existence of an invisible barrier that prevents women from reaching the top of their legal careers—the so-called “glass ceiling”—Patricia Tuma Martins Bertolin, a professor of labor law at Mackenzie Presbyterian University, has developed a study that includes 10 out of the top 20 law firms in the country—as listed in the Chambers and Partners ranking, a UK organization that develops global studies on legal careers. After reviewing the hierarchical structure of these offices, the paper, which was completed in 2016 and published in book form in 2017, found that, while their number was larger at the bottom, women were the minority at the top of the hierarchy in eight of the ten firms surveyed. Intrigued by the two offices that had more women in leadership positions, Bertolin pursued the matter further, conducting 32 interviews. “I found that these firms work with flexible hours, allowing people to work from home—which apparently helps reconcile work and family life,” she shares.

However, despite their flexibility, Bertolin found that working conditions are “calamitous.” The firms demand that the professionals be available around the clock, including nights and weekends, to answer phone calls from clients in different parts of the world. “During the research, I found that men refused to submit to these conditions, but women accepted them in order to get closer to the top of their careers,” she claims. Bertolin reminds us that, in Brazil, it’s only during the last 40 years that women have been in law. During the 1930s, 375 men and only three women applied to join the OAB of the state of São Paulo; in the 1970s, there were 19,000 male applicants and 6,000 female applicants. During the 2000s, these numbers rose to 61,000 and 65,000, respectively.

Aware of this process and concerned about the adverse working conditions of the legal environment, the OAB created the Comissão Nacional da Mulher Advogada (National Commission of Women Lawyers) six years ago. Daniela Lima de Andrade Borges, its current president, shares that, as part of the work of this commission, the statute that governs the profession has been altered. From 2016 onwards, prerogatives for pregnant or lactating women were added; for example, they are exempted from going through metal detectors, and in hearings, they present oral arguments first. It was also made possible to suspend hearings when the only lawyer in a particular case is on maternity leave, and changing rooms were installed in courts. Since March 2019, the OAB no longer accepts applications from law graduates who have been charged with violence against women, the elderly, children, adolescents, and people with physical and mental disabilities.

The Association of Brazilian Magistrates (AMB), created in 1949, has just elected its first woman president. Renata Gil, a Rio de Janeiro judge with a 21-year career, won the election with about 80% of votes; she will represent the Association for the next two years.

Project

Shiftng the teaching of law: Gender and difference in legal education in Brazil (nº 16/08850-1); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Maria da Glória Bonelli (UFSCar); Investment R$71,137.00.

Books

NEDER CEREZETTI, S. C. et al. Interações de gênero nas salas de aula da Faculdade de Direito da USP: Um currículo oculto? São Paulo: Cátedra Unesco de Direto à Educação/Universidade de São Paulo (USP), 2019, 127 pages.

BERTOLIN, P. T. M. Mulheres na advocacia. São Paulo: Lumen Juris, 2017, 260 pages.

Report

Diagnosing women’s participation in the judiciary. Brasília: Conselho Nacional de Justiça, 2019, 28 pages.

Republish