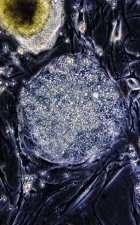

WISCONSIN universityColony of human embryonic stem cells: Waiting for new therapiesWISCONSIN university

In 1998, the team led by biologist James Thomson, from the University of Wisconsin, United States, isolated and developed, for the first time in a laboratory, a lineage of stem cells extracted from human embryos. It was a technical feat and an ethical problem for biological research. A feat, because the studies with these cells may, in theory, lead to better treatments or to the cure of an almost interminable list of diseases. If duly cultivated, embryonic stem cells, and only these, can originate all the tissues of an organism, about 220 distinct kinds of cells that would be the raw material for new therapies. A problem, because the way for getting them offends the belief of portions of society, in particular the religious, and, in some countries, the laws as well: the stem cells are taken out of embryos, which become unviable when they give up this material.

Since then, in several parts of the world, there has been a moral and juridical clash between the defendants and the opponents of this kind of research. Little by little, with a greater or lesser degree of restrictions, there seems to be a tendency for countries that are strong, or minimally structured, in science to permit experiments with genitor cells. In March, President Lula sanctioned the new Law on Biosafety and broadened the prospects for biotechnology in the country: he authorized studies with human embryonic stem cells and the planting and commercialization of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), two lines of research with investments programmed of R$28.3 million, according to the announcement made by the Minister of Science and Technology, Eduardo Campos.

The new Law on Biosafety

Approved by the National Congress under pressure from researchers, civil society as well as the media – attributed to the National Technical Biosafety Commission (CTNBio), formed by twenty seven of notable performance and scientific knowledge, the power to authorize research and oversee the commercial use of transgenics in Brazil. This decision had two immediate consequences: as of May, farmers throughout the country will have access to eleven varieties of genetically modified soya seeds that have been developed by the Brazilian Agricultural research Corporation (Embrapa) and at least a dozen laboratories – many of them having already developed research using bone marrow stem cells and umbilical cord stem cells – should shortly start their investigations with embryonic stem cells, without, nevertheless, being able to carry out the so-called therapeutic cloning.

Cardiologist José Eduardo Krieger, from the Heart Institute (InCor), of the School of Medicine of the University of Sao Paulo (USP), uses an interesting metaphor for describing the importance of encouraging research in this area. “Embryonic cells are the only ones that have the complete hardware of the biological computer”, likens the researcher. “The researches are now going to try to unveil the specific software, the right buttons, that orientate the formation of the various tissues.”

Over the last few years, while work with embryonic stem cells of human origin remained banned, Brazilian scientists did not wait around with their arms crossed. They did what the legislation allowed: they developed lines of research with animal stem cells and human stem cells removed from adult tissue, generally bone marrow and the blood from the umbilical cord. A good deal of the studies involved basic biology. This involves the intuition of trying to understand and control, in vitro, the division and differentiation mechanisms of stem cells and, in certain cases, it involved generating models of animals with some sort of minor lesion. Others have shown a more applied characteristic, in which possible therapies based on adult stem cells were tested in animals and humans. There is no irrefutable evidence that adult stem cells can be as flexile as embryos. However, as each day that passes, it is being discovered that they can be extracted from more mature tissue than had been thought – fat is one of their sources – and they differentiate within a wider range of tissues. Perhaps they may well form the basis for the treatment of some illnesses, such as cardiac, orthopedic and dental problems.

Less versatile than the embryonic ones, the adult stem cells have one advantage: they seem to be safer. In experimental therapies, stem cells are injected into patients, and they are usually taken from the patients themselves. This eliminates the risk of the implanted material being rejected and reduces the occurrence of other problems. “Many studies show that, in mice, when undifferentiated embryonic stem cells are injected, tumors appear”, says Marco Antonio Zago, the coordinator of the Cell Therapy Center of the Ribeirão Preto Faculty of Medicine, of the University of São Paulo (USP). “It would be madness to inoculate embryonic cells into humans, before we learn to differentiate them”, says geneticist Mayana Zatz, the coordinator of USP’s Human Genome Study Center, who is researching into the use of cell therapy in muscular dystrophies (see the interview).

That is why no serious research group, here or abroad, is cogitating to inject, in the short term, a dose of embryonic stem cells into our species. In the next two or three years, the most heartening results, in clinical terms, should come from experiments with possible therapies based on adult stem cells, treading a more cautious path. There is a successful precedent that justifies moderate optimism with this approach. Of all the promises of cell therapy, only one, for the time being, has become a medical procedure that has become routine in leading hospitals: the bone marrow transplant, used, for 40 years, to treat leukemias, certain kinds of lymphomas, and other blood disorders. In the “miracle” of the transplant, the “saint” about which almost nobody used to talk until a few years back, is the population of adult stem cells existing in this soft and spongy issue located in the insides of the bones. There are two kinds of stem cell in the marrow: the hemopoietic ones, which generate the red blood cells, (erythrocytes), the white blood cells and the platelets; and the mesenchymal ones, capable of originating distinct tissues, like bones, cartilage, tendons, muscles and fat.

In the more basic area, progress may come from the most varied fronts: work with adult stem cells, of human or animal origin, cultivated in the laboratory, or implanted in animals, or even in man; studies with human embryonic cells in vitro, or injected into animals; and experiments with embryonic cells from animals. Some lines of applied and elementary research with stem cells pursued by Brazilian scientists are set out below.

Cardiology

Along with Germany, Brazil is one of the international points of reference in clinical research that uses stem cells from the bone marrow of the patients themselves to treat their heart problems. In February, delighted with the positive results of pilot studies carried out with a small number of patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy, chronic ischemia and Chagas’s disease, the Ministry of Health launched a R$ 13 million project to research, over the next three years, the effectiveness of the employment of cells from the marrow against these malfunctions that can lead to cardiac insufficiency. Ambitious, the so-called Randomized Multicentric Study of Cell Therapy in Cardiopathy will be coordinated by the Laranjeiras National Cardiology Institute (INCL), in Rio de Janeiro, and will count on the participation of about 30 universities and hospitals from north to south of the country. The new approach will be tested on 1,200 patients, split, according to their heart problem, in four groups of 300 individuals. They will all receive the conventional treatment for their cardiac problem and will be followed up for one year. To gauge the possible beneficial effects of cell therapy, half of the patients will also be the object of a dose of a placebo (an innocuous material, without any therapeutic effect), and half, of an injection of stem cells into the heart. The study will be double-blind: doctors and patients will not know who has received what.

For each pathology, there will be a center coordinating the studies. The INCL will be in charge of the work with dilated cardiomyopathy (the heart increases in size and has difficulty in pumping the blood). InCor will be commanding the studies with chronic ischemia of the heart. The Santa Izabel Hospital, of Salvador, in collaboration with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) of Bahia, will supervise the research with Chagas sufferers, without precedent in the world. The Biomedical Sciences Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (ICB/UFRJ), along with the Pro-Cardiac Hospital, will head up the experiments on acute myocardial infarction.

If, at the end of the study, some cell therapy is more benefic than the treatment available today for the problems of the heart, the procedure will come to be adopted by the public hospital network. “A year and a half from now, we should have the first results with regard to the effectiveness of the use of stem cells from the bone marrow to treat infarction”, reckons Antonio Carlos Campos de Carvalho, from the INCL. “For the other cardiopathies, we should have to wait about three years.” In the patients with acute infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy and Chagas’s disease, the cell therapy (or the placebo) will be administered by means of a catheter in the coronary arteries. In the victims of chronic ischemia, people who have had an infarction over six months ago, but continue to have problems of irrigation in the heart, the stem cells will be introduced directly into the cardiac muscle during a surgery to implant a saphenous or mammary bypass graft. There is great expectation with regard to the tests with seriously ill sufferers from Chagas’s disease who have developed cardiac insufficiency and are candidates for a heart transplant. Normally, the majority of these patients dies in less than two years. “In preliminary studies, only two of the 30 patients in which we injected stem cells died”, says Ricardo Ribeiro dos Santos, the coordinator of the Fiocruz Tissue Bioengineering Millennium Institute in Salvador. “But neither was because of the therapy.” According to Santos, a good number of the Chagas sufferers showed an improvement in the quality of life and of the cardiac functions.

Two criticisms are being made of the Brazilian studies with cell therapies against cardiac problems. The first snag: the experiments have made very rapid progress, creating overblown expectations of success for the lay public, before having exhausted all the work with animals and discovered the ideal way of injecting stem cells into the sick. “Nobody knows what is the best kind of cell for use in the therapies, nor what is the ideal technique for administering them to the patients”, says cardiologist Edimar Bocchi, from InCor, whose work with adult stem cells in cardiac patients is not part of the Ministry of Health’s mega-study. The second criticism: the researchers do not know the mechanisms that are behind the possible cardiac improvement seen in the preliminary studies. Up until now, there is no certainty as to whether the bone marrow cells benefit the heart because they increase its vascularization, create more cardiac muscle, or remove damaged cells from the heart. “We only decided to do tests on humans after having worked with animals and being convinced that the risks from the employment of stem cells are lower than the benefits”, ponders Radovan Borojevic, from the ICB/UFRJ, one of the researchers heading the researches with stem cells in cardiology. Be that as it may, the Brazilian work was authorized by the National Council of Ethics in Research (Conep) and is forming a school abroad. The Texas Heart Institute recently began a clinical test with stem cells from the bone marrow, inspired on the Brazilian studies. Thirteen patients were given the alternative therapy, and the results are heartening.

Diabetes and autoimmune diseases – The effectiveness of the employment of adult stem cells for controlling disorders originating in the patients’ own immune system is now being tested in Brazil. The group led by researcher Júlio Voltarelli, from USP’s Cell Therapy Center in Ribeirão Preto, has, for example, carried out 30 transplants of stem cells from the bone marrow in people with multiple sclerosis, 15 in victims of rheumatic diseases, and 5 in type 1 diabetics (who need to take insulin in their daily lives). Before being given the therapy, administered intravenously and with cells previously taken from the patients themselves, those taking part in the study were submitted to sessions of chemo- or radiotherapy, to eliminate from the organism the cells of the defense system, responsible for unleashing the autoimmune diseases. “There were five deaths of people with rheumatic diseases, and four from multiple sclerosis, as a consequence of complications, usually infectious, of the therapy”, Voltarelli claims. “There were no deaths amongst the diabetics.” The patients who survived either improved or had their diseases stabilized, an indication that the stem cells may have helped in the reconstitution of a healthier immune system. Now, the group from Ribeirão Preto is going to start, in partnership with the Albert Einstein Hospital, in São Paulo, and the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), a project for transplanting adult stem cells in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (a neurodegenerative disease).

Dentistry

Teeth derived from the cultivation of adult stem cells? At least in animals, producing a canine or molar tooth is almost a reality. In July last year, a couple of dentists from the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), Silvio and Monica Duailibi, published an article in the scientific magazine Journal of Dental Research, n which they described the formation of primitive teeth, following the cultivation of stem cells taken from the milk teeth of rats with an age of 3 to 7 days. The researchers fostered the growth of the cells in a medium rich in a biopolymer and implanted them in a much vascularized region of the animals’ abdomen. After three months, dental coronas began to form there. Before this study, a group of researchers from abroad had already achieved the same feat, except in pigs. Run in collaboration with scientists from the Forsyth Institute, in Boston, and from the Massachusetts General Hospital, the experiment with the rodents was done during a spell when the Brazilians were studying in the United States, and it earned the multinational team a patent. Today, back in Brazil, the Duailibis have achieved similar results in the laboratories at Unifesp. And they did not stop there. “We made teeth grow in the jawbone of rats, using the animals’ stem cells”, tells Monica, who should shortly be publishing an article on the new work. The next step is to try to cultivate, still in rodents, adult cells taken from human teeth. “We are going to exhaust all the research with animals before starting tests with human beings”, Silvio says.

Neurology

Some research groups in the world have produced, in animals and in vitro, nerve cells from stem cells, a feat that increases the hope of one day finding a cure for the neurodegenerative diseases, like Parkinson’s disease. In Sweden, scientists have reverted symptoms of Parkinson’s using a scarce and polemical matrix of biological material, stem cells taken from aborted fetuses, which have the capacity of transforming themselves into neurons. That is why science is seeking other sources of stem cells equally capable of transforming themselves into brain cells. Luis Eugênio Mello, from Unifesp, tried to produce neurons from the cultivation of stem cells taken from the blood of the umbilical cord. He succeeded, but the number of neurons obtained, small, did not overjoy him. “This is not good material for getting nerve cells”, says Mello, who intends to work, in the short term, with a human strain of embryonic cells imported from the United States. Neuroscientist Rosalia Mendez-Otero, from UFRJ, tells a similar story. She has taken neural stem cells from the brains of rats and mice and cultivated them until they became neurons. The process, though, was very slow. “It would take from 12 to 1q5 days for the cells to divide and produce neurons”, Rosalia comments. With the embryonic stem cells, getting neurons can be a quicker process. In a more applied line of research, the scientist from UFRJ is testing the use of cells from the bone marrow to revert the symptoms of a stroke. The result with the first patient was good. “Now we are going to test the therapy on another 25 persons”, explains Rosalia.

Basic research

Since the end of last decade, Lygia da Veiga Pereira, the head of the Molecular Genetics Laboratory of the Biosciences Institute (IB) of USP, has been a pioneer in the country in establishing lineages of embryonic stem cells from mice. In 2001, anchored on this knowledge, she produced the first Brazilian transgenic mice, guinea pigs that had one gene modified and which could be animal models for studying diseases. Like other Brazilian researchers, Lygia learnt, in animals, to master some chemical recipes that steer the process of differentiating embryonic stem cells. “To induce the production of neurons, we add retinoic acid to the culture medium”, exemplifies the researcher from IB/USP. “To get blood, we put in some interleukins (a family of proteins).” Logically, the process of cell culture is not as simple as that, but today one knows at least that some ingredients are indispensable for inducing the stem cells to generate certain kinds of tissue. Before the end of this year, Lygia should start work with imported human embryonic stem cells.

In Ribeirão Preto, the group led by Dimas Covas, from USP’s Cell Therapy Center, has already mastered a good part of the process of transforming mesenchymal and hemopoietic stem cells, the two main kinds of genitor cells present in the human bone marrow, into several tissues, like bones and blood. They also know how to take mesenchymal cells from various sources. “You can get these cells from veins and arteries and from the blood of the umbilical cord”, explains Zago, the coordinator of the center. One of the main objectives of his studies is to map out which genes are activated during the process of transforming the stem cells from the bone marrow into more specialized tissues.

Basic research is costly, time-consuming, and intricate. As times polemical, as in the case of the stem cells taken from human embryos, or without the results expected a priori (gene therapy, for example, is a promise that has not yet been fulfilled). But without investment in science, no one is not going to arrive at new treatments. Do you want one example that it is worth investing in the progress of knowledge? Last month, scientists from the University of Wisconsin, them again, developed a way of cultivating embryonic stem cells of human origin, without the need for keeping them in contact with biological material taken from mice. An important step for producing lineages of embryonic stem cells not contaminated by animal cells, an indispensable condition for their use in humans.

Cells Of Discord

Some countries have recently created laws that lay down the rules for research with stem cells taken from human embryos and so-called therapeutic cloning. How eight countries deal with the theme is set out below.

United Kingdom

Since the beginning of 2002, research with embryonic stem cells specially created for this purpose has been permitted. Therapeutic cloning is also authorized, proved that it uses embryos that have lived 14 days at the most. Two teams have now been given the green light to clone human embryos for therapeutic purposes.

South Korea

In February 2004, a South Korean team was the first in the world to clone human embryos and to take embryonic stem cells from them. It was, however, only at the end of last year that the Seoul government officially defined its policy for the sector. Research with embryos and therapeutic cloning were approved.

Japan

Although there is no law regulating the subject, in July last year the Ministry of Health authorized researches with embryonic cells and therapeutic cloning.

Brazil

The Law on Biosafety legalizes research with embryonic stem cells taken from surplus embryos, not used for reproductive purposes by couples with infertility problems, provided that they have been frozen for three years. There has to be consent from the couple that generated the embryos for them to be set aside for science. Embryos unviable for human reproduction may also go for research. Therapeutic cloning is prohibited.

United States

Since August 2001, President George Bush only sets aside federal budgetary funds for studies carried out with the few lineages of embryonic stem cells that had been created up to that date. But the states have the autonomy to create their own laws, and private enterprise may also finance the researches. Last year, California approved US$ 3 billion for studies with embryonic cells and therapeutic cloning.

France

In August 2004, a revision of the law on bioethics authorized, for a five-year period, research to start with embryonic stem cells using surplus material kept in artificial reproduction clinics. Therapeutic cloning continues to be prohibited.

Germany

Authorizes research with embryonic cells, provided that the lineages studied have been brought from abroad and were created before January 1, 2002. Authorization has to be applied for to import the lineages. Strictly speaking, the law makes it inviable to carry out research in this area.

Portugal

A juridical void rules over the issue. In practice, researches with embryonic cells are not authorized.