David Ramos / Getty ImagesSince 2017, a research group led by American ecologist William Ripple of Oregon State University has been publishing annual articles on the current state of the climate crisis in the journal BioScience. The data in this year’s report, released on October 8, is even more alarming than in previous years: 25 of the planet’s 35 “vital signs” are at record low levels and are on a downward trend for the coming years. In the 2023 article, 20 of the indicators were in critical condition. The initiative condenses data and studies on atmospheric and oceanic temperatures, the rates at which ice is melting in Greenland and Antarctica, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and other parameters. “We are stepping into a critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis,” Ripple said in a statement.

David Ramos / Getty ImagesSince 2017, a research group led by American ecologist William Ripple of Oregon State University has been publishing annual articles on the current state of the climate crisis in the journal BioScience. The data in this year’s report, released on October 8, is even more alarming than in previous years: 25 of the planet’s 35 “vital signs” are at record low levels and are on a downward trend for the coming years. In the 2023 article, 20 of the indicators were in critical condition. The initiative condenses data and studies on atmospheric and oceanic temperatures, the rates at which ice is melting in Greenland and Antarctica, deforestation, biodiversity loss, and other parameters. “We are stepping into a critical and unpredictable new phase of the climate crisis,” Ripple said in a statement.

– Greenhouse gas production increases by 1.3% worldwide but falls 12% in Brazil

– Nature-based solutions can inspire climate change adaptations

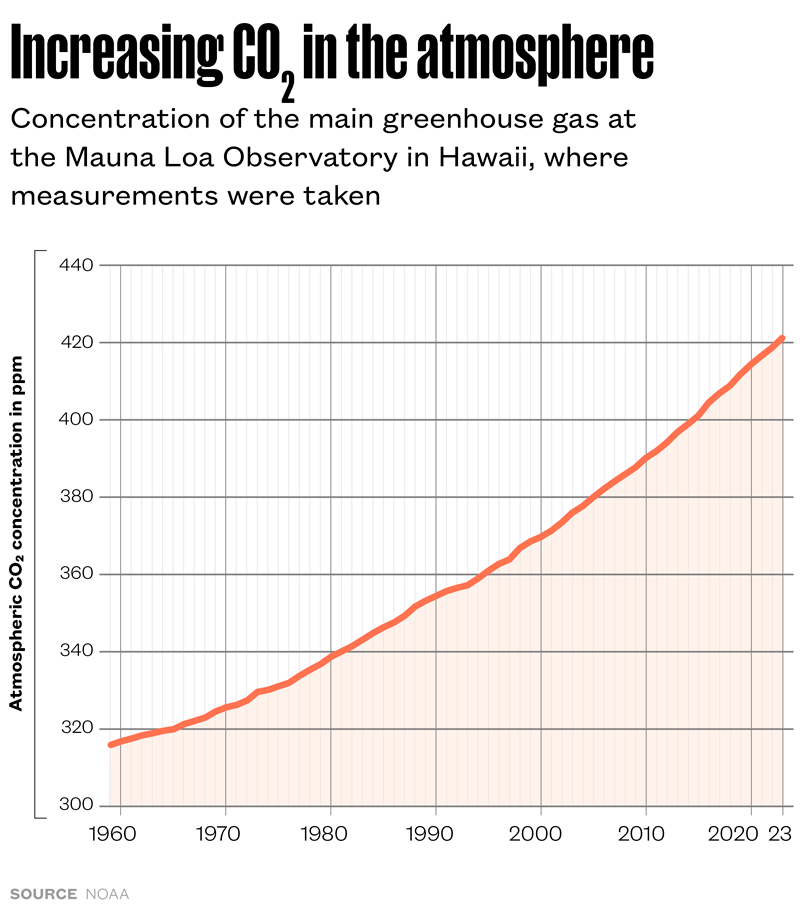

The data point to unprecedented atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), the main greenhouse gases. The current average concentration of CO2, the most common of them, exceeded 420 parts per million (ppm), 50% more than in the preindustrial period (see graph, below). Methane production has also accelerated in recent years. A major driver of methane emissions is the enteric fermentation of ruminants (cows, goats, and sheep). Every 24 hours, the total number of ruminants worldwide grows by 170,000 animals, almost the same rate of growth as the planet’s human population, which increases by around 200,000 people per day.

The article highlights that the planet’s average surface temperature is at the highest level ever measured, as is ocean acidity. The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are at their lowest ever point and the thickness of the glaciers is decreasing rapidly. Instead of reducing fossil fuel consumption as we should be doing, it increased by 1.5% in 2023 and remains 14 times greater than the use of solar and wind energy. Production of these two clean forms of energy increased by 15% in the past year. However, according to the study, this increase is only enough to meet the rising demand for electricity and has not replaced the use of fossil fuels as the main energy source in most countries. These are just some of the planet’s worsening vital signs that are highlighted in the article, written by 14 researchers.

One of the authors, Brazilian ecologist Cássio Cardoso Pereira of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), says there is no way to determine which of the indicators is most worrying. “All signs point to the same problem: the world is heading towards a catastrophic climate collapse,” he says. Pereira highlights that the current rate at which the temperature and acidity of the oceans is rising—one of the most significant forecasters in the field of ecology—is expected to devastate coral reefs, which are home to a huge variety of species. This will likely have a cascade effect on marine biodiversity, exacerbating the extinction process caused by other human activities.

Mauro Galetti, a biologist from São Paulo State University (UNESP), also highlights biodiversity loss as one of the most alarming ecological signs. “Fauna is associated with important ecosystem services that are difficult to observe in day-to-day life,” says Galetti, who wrote the first article on Earth’s vital signs with the team led by Ripple in 2017. The extinction of species that play an important role in maintaining an ecosystem like the Amazon—by promoting the pollination of plant species, for example—can lead to a loss or reduction of these services, which can affect the local economy. One of the Amazon’s major contributions to the regional climate is that it is the source of some of the rain that falls over the Central-West and Southeast regions of Brazil.

One of the few positives cited by the article is the decrease in deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon in 2023, in direct contrast to the trend seen globally last year. According to the article, the drop in deforestation was likely due to changes in environmental policy at the federal level. However, other problems have plagued the rainforest, such as droughts and wildfires, which have contributed to its degradation.

Biologist Philip Fearnside of the Brazilian National Institute of Amazonian Research (INPA) explains that the unprecedented drought was caused by a combination of the El Niño and the Atlantic Dipole phenomena, which alter rainfall patterns in various parts of the world. El Niño is characterized by above-average warming of surface waters in the eastern and central regions of the tropical Pacific. The Atlantic Dipole causes differences in water temperature between the southern and northern Atlantic, resulting in periods of drought in the southern Amazon. “What kills trees is a combination of high temperatures and drought,” says Fearnside. As for forest fires, he attributes the vast majority to human activity, some of which are criminal in nature.

A decline of the planet’s vital signs increases the occurrence of fatal and costly disasters, such as the heavy rainfall and floods that killed at least 200 people in the Valencia region of Spain at the end of October. The BioScience article highlights a number of cases of heavy rainfall, flooding, heatwaves, and major forest fires that occurred between November 2023 and August 2024. These extreme events have caused thousands of deaths and billions of dollars in damage.

To fully understand the consequences of the climate crisis, we still need to investigate feedback loops that may reinforce the deterioration of the climate situation. Pereira warns about the melting of permafrost (frozen soil that covers a quarter of the land surface of the Northern Hemisphere) in the Arctic region due to global warming. The ice present in this soil holds billions of tons of methane and carbon dioxide. When it melts and evaporates, the concentration of these gases in the atmosphere increases, leading to higher temperatures, thus causing the permafrost to melt even more in a vicious cycle.

The Oregon group’s paper also makes other recommendations, such as including climate change in school curriculums and the controversial idea of controlling population growth. Patrícia Morellato, a biologist from UNESP, agrees that climate change should be included in education, from elementary school to university, in all courses. She also believes that population control makes sense. “There is no such thing as an infinite resource and population growth cannot be infinite, even if we manage to use technology to produce more food in a smaller area,” says Morellato, director of the Center for Research on Biodiversity Dynamics and Climate Change (CBioClima), one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs) funded by FAPESP. She notes, however, that any public policy on this issue would need to take into account a woman’s right to make their own reproductive decisions and that we need to analyze the experiences of countries where this kind of measure has already been taken.

The story above was published with the title “Earth’s health declines” in issue 346 of December/2024.

Scientific article

RIPPLE, W. J. et al. The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth. BioScience. Oct. 8, 2024