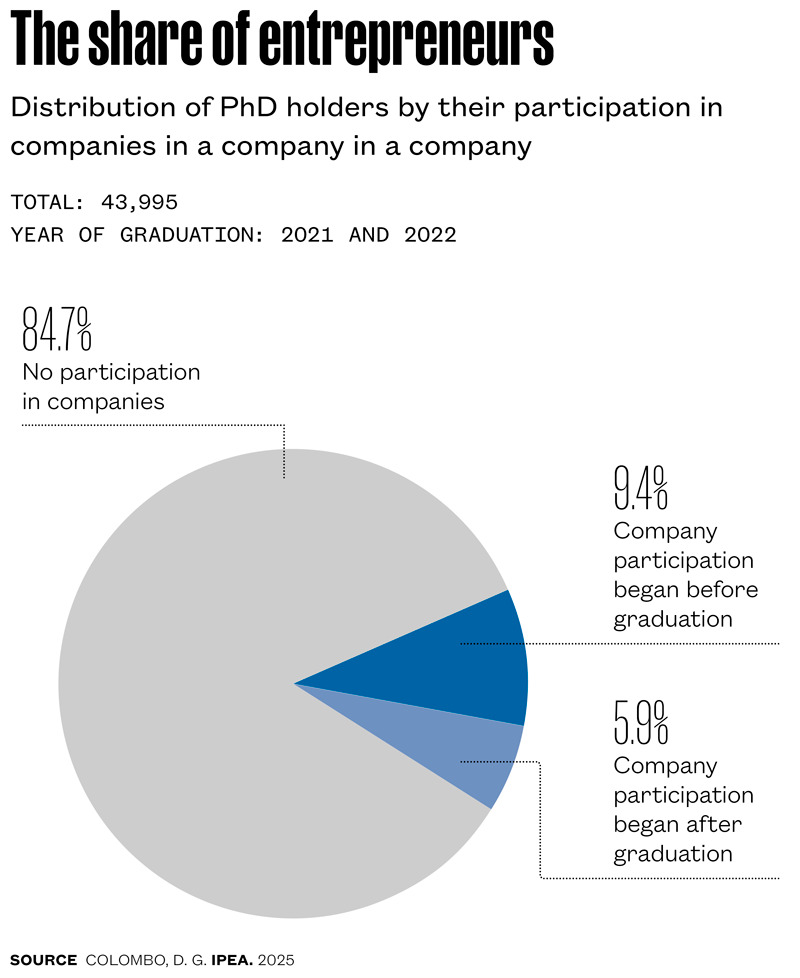

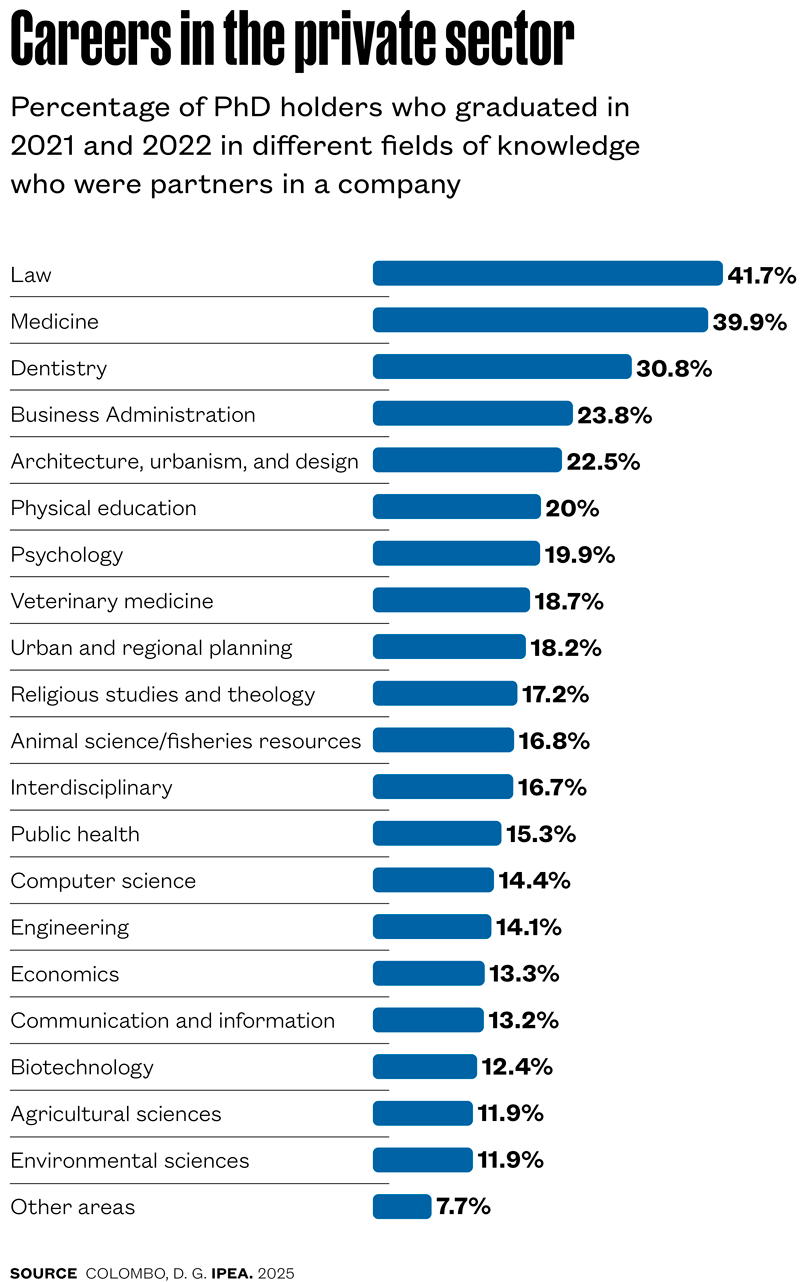

A study by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) published in April found that, among the 44,000 PhD graduates in 2021 and 2022, 15.3% (6,700) were business owners or administrators as of July 2024, between 18 and 36 months after earning their degrees. Most of them, around 62%, work in management, holding positions such as president, director, or managing partner. According to the data, 54.7% run microbusinesses, 14.6% are owners or managers of small businesses, and 30.7% run medium or large businesses. The main economic activities of these businesses were health (28.2%), education (11.1%), and legal activities, accounting, and auditing, which together make up the category that corresponded to 6.2%. Looking at the PhD graduates by field of study, law had the highest percentage of business owners or partners, with 41.7% of the graduates, followed by medicine (39.9%), and dentistry (30.8%).

According to the author of the study, economist and coordinator of methods and data at IPEA, Daniel Gama e Colombo, the data indicate varied profiles of entrepreneurial PhD holders, even though the study did not include a qualitative assessment. The fact that more than half are classified as micro-entrepreneurs, associated with certain characteristics of their fields of knowledge and economic activities, suggests there is a process of labor precarization and a common practice in Brazil known as “pejotização.” In this practice, professionals are hired through their own companies rather than as formal employees to perform regular, ongoing work under conditions similar to fulltime employment, often without employment benefits, placing it in a legal gray area. “When we look at the activities of these companies, the category education ranks in second place. Since it is the main employer of PhD holders in Brazil, it is possible that the high number of legal entities is linked with pejotização and precarization, with professionals with PhDs being hired without employment rights,” he notes.

Another group appears to be genuinely entrepreneurial, creating businesses based on the education they received at universities. “Around 22% of the legal entities are companies that are not classified as micro or small businesses. These cases may not fall under a pejotização strategy, although we do not have concrete data to confirm this,” says Colombo.

Among the PhD holders with registered companies, around 60% already had a Brazilian Corporate Taxpayer Registration number (CNPJ) before completing their degree. This suggests a third profile: individuals taking a graduate degree to improve their qualifications and earnings in the activities they were already engaged in, and not necessarily for entrepreneurial purposes. This may explain why the fields of knowledge with the highest concentration of business owners include law and medicine, among other regulated professions. “In this case, there may not be any academic vocation or genuine interest in entrepreneurship, taking knowledge produced in academia to the market with some innovation, but rather the aim of improving one’s qualifications to gain an advantage in their practice or office,” he explains.

For physicist Anderson Gomes, a researcher at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) who did not take part in the IPEA study, this type of qualification can play an important role in taking new knowledge into society. “I have graduate dentistry students seeking their master’s degrees and PhDs in order to gain a competitive edge in their practice. By doing so, many end up offering their clients new technologies that they discover through contact with the university,” says Gomes, who is currently the director of the Center for Management and Strategic Studies (CGEE), a research center affiliated with the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation.

He notes that these two types of students, as well as master’s and PhD graduates working as independent contractors and those who have opened technology-based startups, all end up being referred to as entrepreneurs. “They are all given the same label, but need to be separated. That is why these studies are important and need to advance, so that we can better understand this scenario,” he states.

The Brazilian graduate system was created in the 1960s with the primary purpose of training faculty and researchers for Brazilian universities, and for a long time it fulfilled this role effectively. The large expansion in the number of PhD holders over the past two decades—currently, there are approximately 25,000 new graduates each year—and the limited number of teaching positions in public higher education institutions have led some graduates to seek alternatives in the formal job market, working as researchers contracted by private companies, in the nonprofit sector, or through entrepreneurship.

The analysis of entrepreneurial PhD profiles is important, as it highlights the paths taken in seeking opportunities beyond academia. According to Colombo, the expansion of graduate programs has brought significant benefits to individuals and society, including greater employability, higher salaries, innovation, and human capital. “However, some key challenges remain. One of these is the underutilization of doctoral graduates in the workforce, since many work in positions below their level of qualification,” he says. In an earlier study conducted in 2024 on PhD holders in formal employment, Colombo found that approximately 85% of those working outside of the education sector had jobs that did not fully make use of their advanced training.

“The evidence suggests that organizations and the national economy make poor use of these individuals’ stock of knowledge,” he observes. The problem is also present in other countries. He highlights a report from 2023 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which deals with the growing precarity of doctoral and postdoctoral research careers in member countries, driven by the increase in the number of graduates and by the scarcity of permanent academic positions. One of the initiatives that may help support the development of these researchers is providing entrepreneurship training to students, one of the recommendations of the report. “Additionally, the OECD recommends other actions: internship programs in companies, incubator policies, and mentoring programs, for example, are some possible initiatives that are more practical and promote the development of entrepreneurial skills,” explains Colombo.

“The evidence suggests that organizations and the national economy make poor use of these individuals’ stock of knowledge,” he observes. The problem is also present in other countries. He highlights a report from 2023 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which deals with the growing precarity of doctoral and postdoctoral research careers in member countries, driven by the increase in the number of graduates and by the scarcity of permanent academic positions. One of the initiatives that may help support the development of these researchers is providing entrepreneurship training to students, one of the recommendations of the report. “Additionally, the OECD recommends other actions: internship programs in companies, incubator policies, and mentoring programs, for example, are some possible initiatives that are more practical and promote the development of entrepreneurial skills,” explains Colombo.

The IPEA study adopted a broad definition of entrepreneurship, based on participation by doctoral graduates in Brazil’s Corporate Taxpayer Registry (CNPJ) as owners or administrators. In it, entrepreneurship is defined as any case of starting, owning, or managing a business, either as a self-employed individual or as a company. Colombo notes that there are different definitions in other countries, and there is no consensus among the researchers in the field about which is the most accurate. “One report on PhD holders in the United Kingdom that I cite in the study, by the National Centre for Universities and Business, for example, defines entrepreneurs as ‘those who have run their own businesses or considered themselves self-employed or are at the conceptual phase,’” says the IPEA researcher. The conceptual phase precedes the start of the business, when the entrepreneur is investigating and assessing the viability of the venture.

The percentage of new PhD graduates who own a business in Brazil is higher than that reported in studies conducted in the USA (9% among PhD holders in science, engineering, and health), in the UK (7% in 2019 and 2020), and in Europe (6.8% of the PhD holders from nine universities in the region between 2016 and 2020 were self-employed). Since there are methodological differences among these studies, it is not possible to make a direct comparison. “Even so, it appears that the Brazilian case reveals a high rate of entrepreneurship,” notes Colombo.

For Márcio Florêncio, who holds a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the Federal Institute of Piauí (IFPI) and did not take part in the study, the IPEA data can be seen from two perspectives. “On one hand, it may indicate that these new PhD graduates are managing to transform the results of their research into products or services. On the other, it may signal a lack of opportunities, which leads them to become entrepreneurs out of necessity,” says Florêncio, one of the coauthors of a literature review on entrepreneurship among researchers in Brazil, published in Revista Gestão em Análise in February 2023. The survey showed that most of the articles on the topic focused on identifying entrepreneurial characteristics and skills in undergraduate students, while less attention was given to graduate students.

Another study published in December 2021 by CGEE also analyzed the number of graduate degree holders who were part of the shareholding structure of Brazilian companies, using a larger sample and covering a longer period of time. The study examined a group of 512,218 master’s and 197,282 PhD holders in Brazil, as well as 14,705 PhD holders who earned their degrees abroad, all in the period from 2003 to 2017. The percentage of company partners among the PhD holders who graduated in Brazil was 16.8%, a little higher than the 15.3% found by IPEA. Among those who studied abroad, the rate reached 21.4%. Another result that aligns with the IPEA data concerns the fields of business activity.

In the analysis by CGEE, the predominant fields among PhD holders in Brazil were health sciences—32.1% of them were among the owner-partners—followed by applied social sciences, with 28.2%. “Although some results are qualitatively similar, it is not possible to know if this percentage of entrepreneurs has grown or shrunk, because they are different samples,” observes Gomes, from CGEE.

Some universities are actively working to transfer the knowledge generated in their graduate programs to society. The University of Campinas (UNICAMP), for example, publishes the list of its “child companies,” businesses created by its students and faculty. According to the most recent survey, there are 1,588 companies of this type registered, 1,349 of which are active in the market: 141 (9%) of the registered companies were founded by PhD holders or postdoctoral fellowship researchers, 139 by master’s degree holders, and 879 by undergraduate degree holders. The remainder are companies created by faculty and staff. “Through this mapping, we identify and publicize success stories. This is important so that students can see that it is possible to follow this path,” says Renato Lopes, executive director of Inova, UNICAMP’s innovation agency.

In Florêncio’s assessment, from IFPI, the data on the PhD holders’ entrepreneurship could contribute to the development and strengthening of public innovation policies. “They demonstrate that these professionals are willing to be entrepreneurs, whatever their motivation,” he says.

The story above was published with the title “Entrepreneurial PhD holders” in issue 356 of October/2025.

Scientific articles

COLOMBO, D. G. E. Empreendedorismo de doutores: Análise dos sócios e gestores de organizações recém-egressos do doutorado no Brasil. Radar. No. 78. Apr. 2025

Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos – CGEE. Perfil da formação na pós-graduação de sócios proprietários no Brasil. Serviços de Informação sobre RH para CT&I. Dec. 2021.

SOUSA, R. M. de & FLORÊNCIO, M. N. da S. Empreendedorismo acadêmico à brasileira: Revisão sistemática e insights de pesquisa no período de 2017 a 2021. Revista Gestão em Análise. Vol. 12, no. 1. Feb. 2023.