The proportion of Black, mixed-race, and Indigenous individuals among those completing stricto sensu graduate programs in Brazil has risen over the past three decades, although white individuals still account for two-thirds of the graduates (68.6% of PhD and 62.9% of master’s degree graduates in 2021). In all regions of Brazil, the percentage of white individuals among graduate degree holders is higher than their share of the local population. In the South, white individuals make up 72.6% of the population but accounted for 84.4% of master’s and 85.6% of PhD graduates in 2021.

In the Northeast, white individuals comprised 26.7% of the total population and represented 39.1% of the master’s and 43.9% of the PhD graduates in 2021. A positive highlight is that it is the only region of the country where the proportion of Black individuals in the population (13%) is roughly equivalent to their share of master’s graduates in 2021 (13.5%) and PhD graduates (11.1%). However, mixed-race individuals still face a disadvantage (59.6% of the population, but only 45.4% of the master’s and 42.5% of the PhD graduates).

These data are part of an unprecedented chapter on race and color in the study Mestres e doutores 2024, produced by the Center for Management and Strategic Studies (CGEE), which compiles statistical data on 1,001,861 master’s and 319,211 PhD graduates in Brazil between 1996 and 2021. Part of the results of the study was published last year (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 340). “Although there have been several efforts to increase racial inclusion in Brazilian graduate programs, access remains highly unequal,” notes Sofia Daher, technical advisor at CGEE, who coordinated the study. The situation for Indigenous people is even more unfavorable, with only 196 master’s and 54 PhD graduates in 2021. “Whereas Black and mixed-race individuals have consistently increased their share among graduates in recent years, Indigenous people have experienced slow growth and will need a significant boost to gain representation,” says Daher.

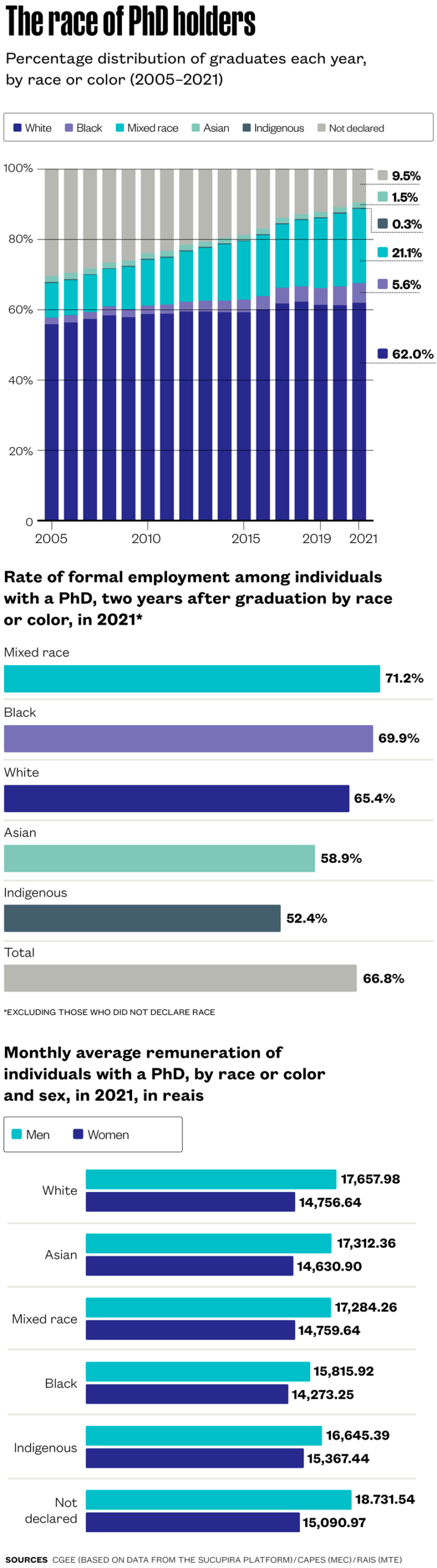

CGEE has periodically published the survey on master’s and PhD graduates since 2010, but this is the first time that the historical series, which includes data since 1996, analyzes the ethnic origin of the graduates. It was difficult to produce this type of analysis in the past due to the large number of graduates who did not declare their race or color on the Lattes CV platform—in 1996, this information was missing for about 47.5% of master’s and 44.5% of PhD graduates. The percentage has decreased over time—in 2021, only 7.9% of master’s and 9.5% of PhD graduates did not declare their race. This enabled, for the first time, the production of data that is representative of reality.

The proportion of Black PhD graduates rose from 1.8% of the total in 1996 to 6.2% in 2021, while that of mixed-race PhD graduates increased from 9.7% to 23.3% over the same period. Anthropologist Pedro Jaime, author of the book Executivos negros: Racismo e diversidade no mundo empresarial (Black executives: Racism and diversity in the business world), was surprised by the growth observed among mixed-race graduates and had expected a greater increase among Black graduates. “What we have seen, from an anthropological perspective, is an identity shift over time in Brazil, with a greater number of people who once saw themselves as mixed-race now self-identifying as Black,” he explains.

The study provided unexpected data about labor market integration. A slightly larger proportion of Black and mixed-race individuals who were able to overcome access barriers and graduate from master’s and PhD programs were in formal employment compared to individuals of other racial groups. Two years after earning their master’s degree, 63.2% of mixed-race and 61.8% of Black individuals were employed in 2021, compared to 57.2% of white, 55.7% of Asian, and 52.9% of Indigenous individuals. Among those who had completed a PhD two years earlier, 71.2% of the mixed-race and 69.9% of the Black graduates had formal employment, compared to 65.4% of white, 58.9% of Asian, and 52.4% of Indigenous graduates.

However, the analysis of remuneration, placed white individuals back at the top. Among men, white individuals with a PhD earned an average of R$17,657.98, R$1,842 more than Black men and R$373 more than mixed-race men. Among women, the salary level was significantly lower: white women with a PhD earned an average of R$14,756.64, almost the same amount as mixed-race women and R$483 more than Black women. The gap is similar among those with master’s degrees: white men are at the top, earning an average of R$12,459.97, and Black women are at the bottom, with R$8,595.87. “Women earn less than men in all regions and in almost every field of knowledge,” explains Daher. “But the situation is worse for Black women, who suffer a two-fold disadvantage.”

According to economist Pedro Vaz do Nascimento Almeida, a researcher specializing in the experiences of Black individuals in the labor market, a more in-depth analysis is required of the employment conditions of Black and mixed-race master’s and PhD holders. “The lower remuneration suggests that they may be facing genuinely unfavorable conditions,” he says. “The country’s labor market has a large base of low-quality occupations, with low remuneration, generally of less than two minimum wages, and these positions are predominantly filled by Black and mixed-race individuals. There are no objective reasons for master’s and PhD holders to be immune to the effects of this aspect of racism in the country,” states Almeida. Before the end of the year, CGEE is expected to publish another chapter of the study, this time about the mobility of master’s and PhD graduates across the country.

The story above was published with the title “Limited diversity” in issue 355 of September/2025.

Republish