Assessing the condition of structures built on the seabed, often hundreds or even thousands of meters deep, is one of the major challenges facing companies involved in offshore oil and gas exploration. An innovation developed in Brazil could help address this problem. After three years of work, a team of researchers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Petrobras, and the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI) presented a system that uses sensors to detect vertical and horizontal displacements and inclinations of the seabed and the structures installed on it, along with acoustic modems to transmit the collected data.

The device’s main innovation is its ability to gather and store information on the condition of oil wells, pipelines, manifolds (sets of valves and accessories that channel production from multiple wells into a collector pipeline), and other equipment, without the use of cables for data transmission. Equipped with long-life batteries that can last from several months to years, the system is designed to operate at depths of up to 2,000 meters.

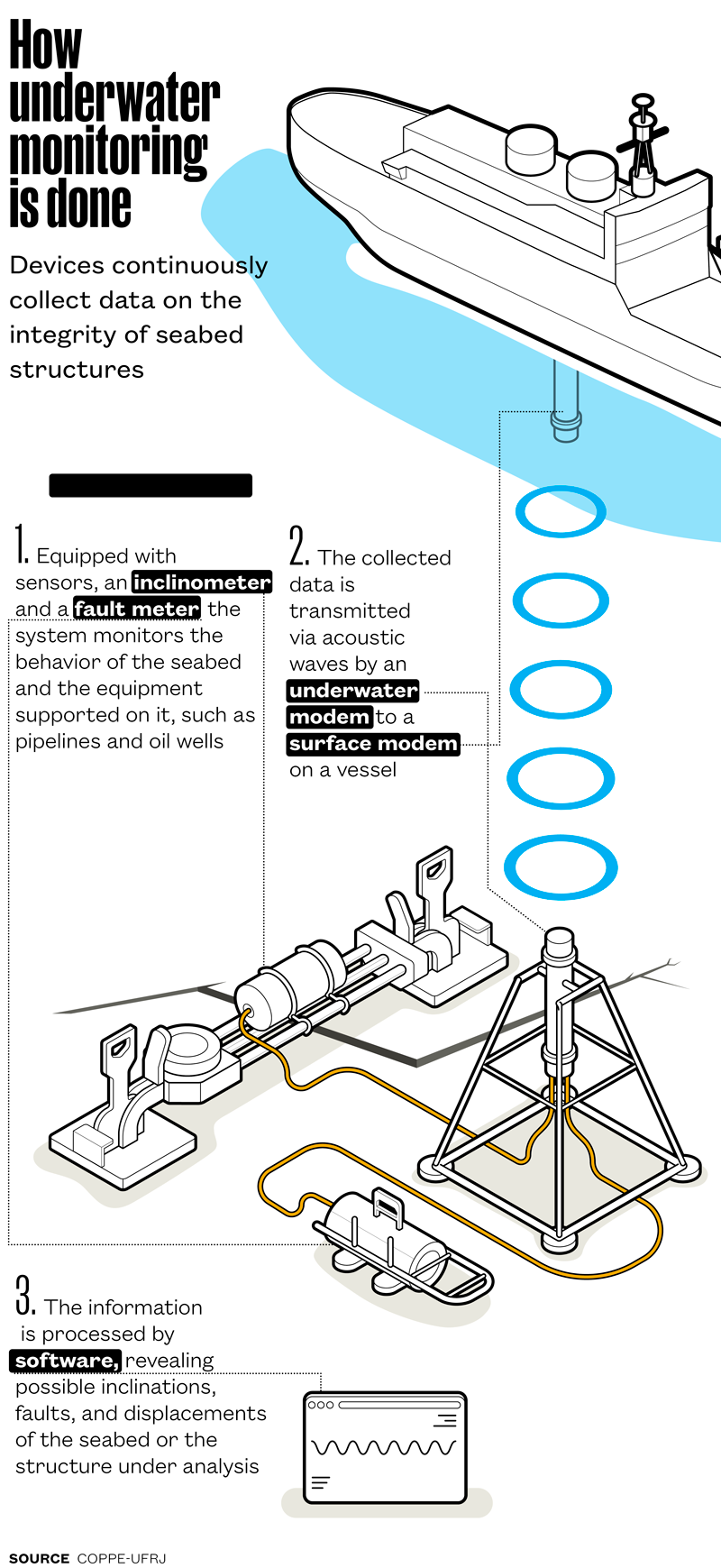

“The information will be retrieved and transmitted via a modem that is part of the system installed on the seabed, which communicates through acoustic waves with another modem near the surface, on a vessel,” explains engineer Fernando Danziger, research leader and coordinator of the Field Testing and Instrumentation Laboratory at the Alberto Luiz Coimbra Institute for Graduate Studies and Research in Engineering (COPPE) at UFRJ. Acoustic modems are devices that convert digital signals into sound waves for communication and data transmission in aquatic environments.

Currently, visual inspection of underwater systems used by the oil industry is carried out by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). This is an expensive method that requires special vessels and qualified teams and provides only a snapshot of seabed conditions. According to the research team, the system they have developed will enable continuous monitoring and more frequent data collection. In the future, the equipment may also be adapted to assess the integrity of offshore wind turbine anchoring structures.

The ocean floor is made up of geological formations similar to those found on land, such as slopes of varying inclines that can fracture and slide, as well as soils that deform under the load of structures supported on the seabed. Movements such as settlement (vertical downward displacement) and tilting of equipment installed on the ground can compromise structural integrity, with safety, environmental, and economic consequences.

“As in onshore situations, it is necessary to monitor these occurrences to detect early changes that may indicate risks and affect oil and gas exploration infrastructure or the proper functioning of wind turbines,” Danziger adds.

The platform consists of two main instruments—an inclinometer and a fault meter—both equipped with sensors (see infographic). Mounted on an underwater structure, the inclinometer can detect small angle variations along two perpendicular axes of the equipment. “It allows us to monitor how the structure rotates around its axes and thus assess whether the behavior of the soil and the structure is consistent with the assumptions made in the project,” explains engineer Gustavo Domingos, a member of the research team, which also included engineers Diovana Della Flôra and João Henrique Guimarães.

In addition to measuring angle variations, the fault meter has a sensor that records the relative distance between parts A and B of the equipment resting on the seabed. The device consists of two square bases, one at each end, connected by a movable metal arm that can extend up to 1.5 meters. “If these parts are positioned on opposite sides of a fault in the moving seabed, for example, we can measure the magnitude of the relative displacements and the direction in which they are occurring,” Domingos explains.

“Imagine we are at a boat dock, with one part of the fault meter fixed to the pier, which does not move, and the other attached to a boat that shifts with the waves,” he says. “The fault meter would detect the boat’s displacements, up and down, as well as moving away from or closer to the mooring.”

The system developed by UFRJ, Petrobras, and NGI was built using accessible technologies, including parts made with 3D printers and sensors that can be adapted to different applications. Long-life batteries power the sensors, which are housed in a watertight capsule that also contains the data acquisition and communication system. According to the UFRJ team, the modems, supplied by the British company Sonardyne, have already been used for several years in the Campos (RJ) and Santos (SP) oil basins.

Luoman / Getty ImagesOil platforms in Guanabara Bay: the system was designed to ensure the safety of oil and gas explorationLuoman / Getty Images

“There are similar systems worldwide that use the same form of wireless data transmission via acoustic modems, but they are designed to monitor temperature, pressure, and other parameters. With the goal of measuring seabed displacement from a geotechnical perspective, I believe our project is pioneering,” says Danziger.

The first talks with Petrobras about the project took place in 2018, but development only began in 2022—delayed by budget-related changes to the project scope and stoppages caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This year, the technology underwent validation tests at COPPE’s Ocean Technology Laboratory (LabOceano), a leading facility for simulating wave and current conditions on vessels and offshore structures.

“As the bottom of the tank is made up of movable plates separated by joints, we were able to install the fault meter between two adjacent plates and simulate their movement, as if a crack were forming in the seabed. With the inclinometer, we measured small variations in the angle of the plates,” explains Domingos.

“By combining high-sensitivity sensors, real-time acoustic data transmission, and a modular architecture that can be customized for different soil types and depths, the system represents a significant step forward in seabed monitoring,” says civil engineer Marcos Massao Futai, from the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (Poli-USP), who was not involved in the study.

According to Futai, who studies the behavior of infrastructure works and their interaction with soil, the continuous and automated measurement capability of the new technology is a positive development for the offshore sector. “In addition to enabling long-term analysis of the geotechnical behavior of the seabed, it contributes to structural integrity and operational safety,” he says. “This multidisciplinary approach, combining geotechnics, instrumentation, oceanography, and computing, makes the proposed solution innovative.”

According to the team, prototypes of the fault meter and inclinometer with acoustic modem transmission are now operational and ready for installation and use by Petrobras. The next step is to incorporate artificial intelligence tools into data analysis, aiming to advance ocean geotechnical monitoring.

The story above was published with the title “The seabed under surveillance” in issue 355 of September/2025.

Republish