A thriving and prosperous society hinges on the education provided to its children and youth, yet in Brazil the basic education system has increasingly become unwelcoming for teachers. For decades, educators have grappled with issues like meager salaries, limited access to laboratories and school libraries, and a lack of societal recognition. The “Education at a Glance 2021” report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) showed that the starting wage for elementary school teachers in Brazil is the lowest among the 40 surveyed nations, even lower than in other Latin American countries, such as Colombia and Mexico.

Data from 2019 reveal that the gross monthly income of public-school educators with a higher education degree averaged at only 78% of the earnings of similarly educated professionals in other fields, according to a National Education Plan (PNE) status report. Mauricio Pietrocola, a physicist from the School of Education at the University of São Paulo (FE-USP), notes that, beyond inadequate pay and overcrowded classrooms, teachers face the challenge of having to address severe learning gaps among students. Often, these combined challenges lead educators to consider leaving the profession altogether. “I often meet former teaching-degree students with a major in physics who are now employed in banks. Many tell me they would have liked to become teachers but opted for public bank positions due to better working conditions,” reports Pietrocola, who is leading a FAPESP-funded research project to explore innovative strategies for natural science education.

The shortage of educators in primary education has reached alarming levels in recent years, a complex issue that requires a historical lens to be better understood, says Pietrocola, who has been investigating these issues for close to 40 years. Between 1970 and 2000, the deficiency in teaching staff was primarily linked to a rapid surge in student enrollments, he explains.

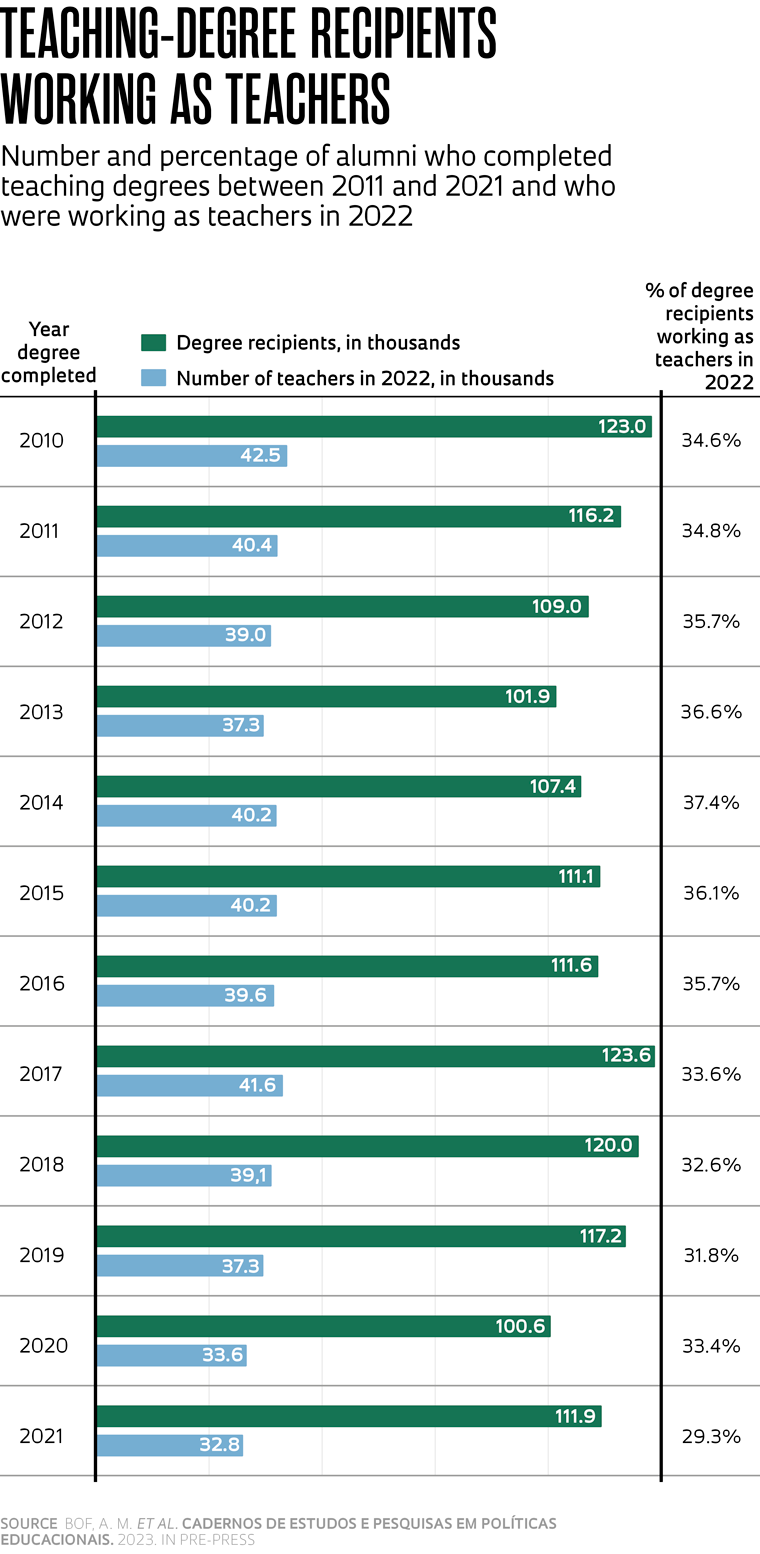

Lúcia Teixeira, president of SEMESP, an institution representing higher education providers in Brazil, recalls that during the 1980s and 1990s, the federal government responded to the increased enrollment by authorizing schools to hire teachers without formal training. This changed in 1996 with the enactment of the National Education Guidelines Act (LDB), or Law no. 9,394, which requires educators to hold formal qualifications in the subject they teach. “However, these provisions of the LDB have yet to be fully implemented,” says Teixeira. In 2021, there were 2.2 million active teachers in primary education, as reported by INEP. But the number of educators teaching in lower secondary education decreased from 779,000 to 753,000 between 2016 and 2021, according to a study published by SEMESP Institute in 2022. The figures for upper secondary education over the same period were 520,000 and 516,000. SEMESP Institute estimates that the shortage of educators in primary education could reach 235,000 by 2040.

However, unlike in previous decades, the current shortage of educators is linked to the devaluation of the profession, says Pietrocola. This problem is not unique to Brazil, he notes, citing an OECD study involving recent graduates from primary education. “In 2015, this study compared the average percentage of students intending to pursue teaching careers across different countries and regions,” he says. According to the study, the global average had fallen from 5.5% to 4.2% over a 10-year period, while in Brazil the figure was even lower at 2.4%. The average for European countries, in contrast, was 20%.

Marcia Serra Ferreira, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and director of teaching-degree programs for basic education at CAPES, cites a 2007 report by a commission established within the Basic Education Chamber of the Brazilian National Education Council (CNE). This report sounded an early alarm about a potential shortage of teachers in secondary education if urgent measures were not taken. The federal government has since launched several initiatives, including the Institutional Program for Teaching Initiation Scholarships (PIBID), offering scholarships to encourage students in teaching-degree programs to work in public schools. “The program has benefited 317,000 students. It currently has partnerships with 248 higher education institutions and 49,200 scholarship recipients across Brazil,” she says. In 2024, Ferreira anticipates an additional 100,000 scholarships will be awarded within the program. Ocimar Munhoz Alavarse, a professor of education at USP, recognizes the importance of these programs but notes that available spots are limited and need to be expanded. “I have around 300 students in the first two years of their teaching-degree program who are eligible for PIBID scholarships, but only 24 have managed to secure a spot,” he says.

Alavarse suggests that the allocation of PIBID scholarships should be based on an analysis of educational data, including future demographic projections. “Brazil’s aging population, as evidenced by the most recent census, could mean that demand for teachers will decline in the coming decades, so it’s essential to estimate demand based on these demographic shifts,” he recommends (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 330).

Vitor de Angelo, chairman of the National Board of Education Departments, highlights the federal government’s initiatives in 2023 to expand full-time schools and enhance the literacy process for elementary school students. “But there’s still a significant gap in addressing the concerns surrounding teachers,” says Angelo, who also serves as Education Secretary of Espírito Santo. This has led to an overhaul of the National Education Plan (PNE), which outlines education guidelines, goals, and strategies for the period 2014–2024. “This initiative couldn’t be timelier. The new PNE needs to be redesigned with initiatives to make teaching careers more appealing and with effective strategies to attract educators to positions in basic education,” Angelo opines.

Project

Study of the implementation of curricular innovations, pedagogical strategies, and emerging technologies for quality-equity in primary education (nº 22/06977-5); Principal Investigator Mauricio Pietrocola Pinto de Oliveira (USP); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Investment R$1,111,669.40.

Reports

Higher Education Census 2021. Brazilian Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP). Brasília: Ministry of Education, 2022.

Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021.

Republish