In May 2023, there was promising news in the fight against drug-resistant bacteria. With the help of AI, researchers from Canada and the USA identified a compound that acted potently and specifically against Acinetobacter baumannii, which often causes serious lung and urinary tract infections in hospital inpatients. The pathogen is on a list drawn up by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 of bacteria against which new treatments are urgently needed because current antibiotics can no longer eliminate them (see report on page 12).

The team, led by James Collins of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), USA, and Jonathan Stokes of McMaster University, Canada, trained a computational model to recognize the properties of 480 compounds that have some effect on A. baumannii from among the 7,684 tested to combat the microorganism. They then presented the model with another 6,680 molecules whose antibiotic action is unknown, so that the program could identify those most likely to kill the pathogen. Within hours, the list of 6,680 compounds was whittled down to 240, something that would have taken days or months using traditional testing methods. Forty of those 240 molecules proved capable of inhibiting the growth of A. baumannii in the laboratory. One—called abaucine—did particularly well and progressed to animal testing. There is still a long way to go, however, before it might become an antibiotic for human use.

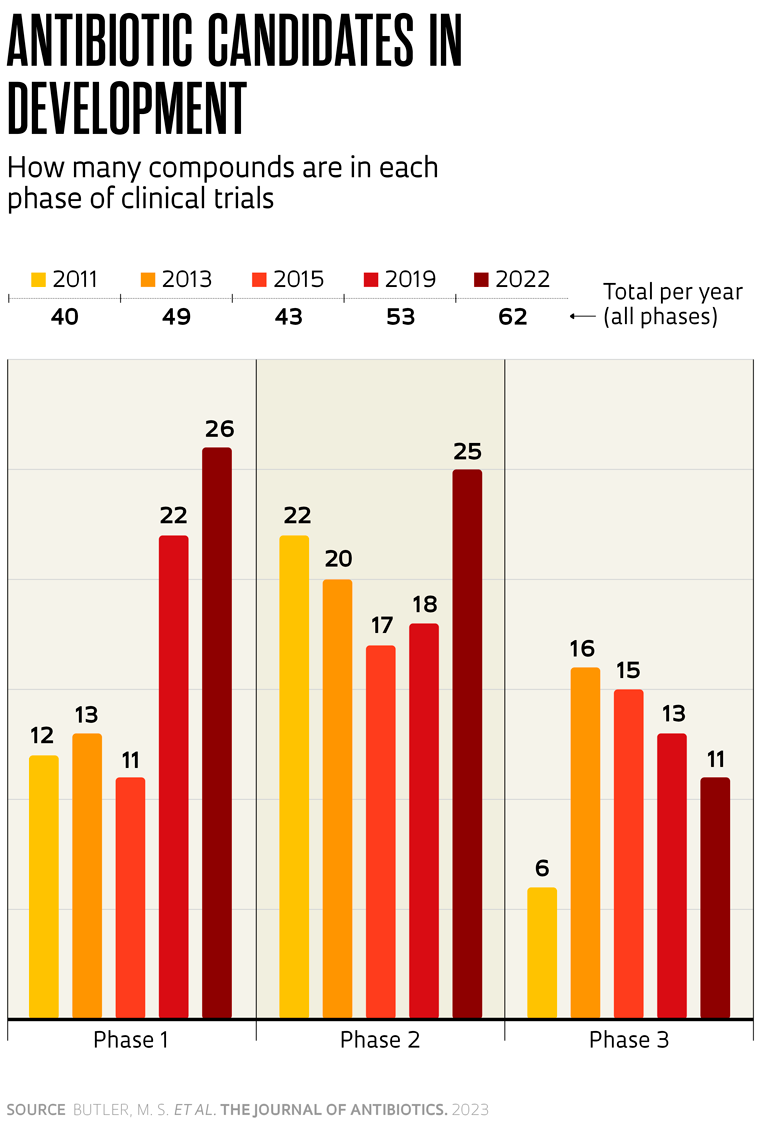

Despite reducing the time spent screening compounds, computational modeling and AI alone are unlikely to solve the problem of antibiotic resistance. The issue is as old as the use of these compounds in modern medicine, and according to experts, a range of measures are needed, from the strictly controlled use of these medicines in human and animal healthcare to the prevention of infections through good hygiene and vaccination whenever possible, in addition to the development of new drugs.

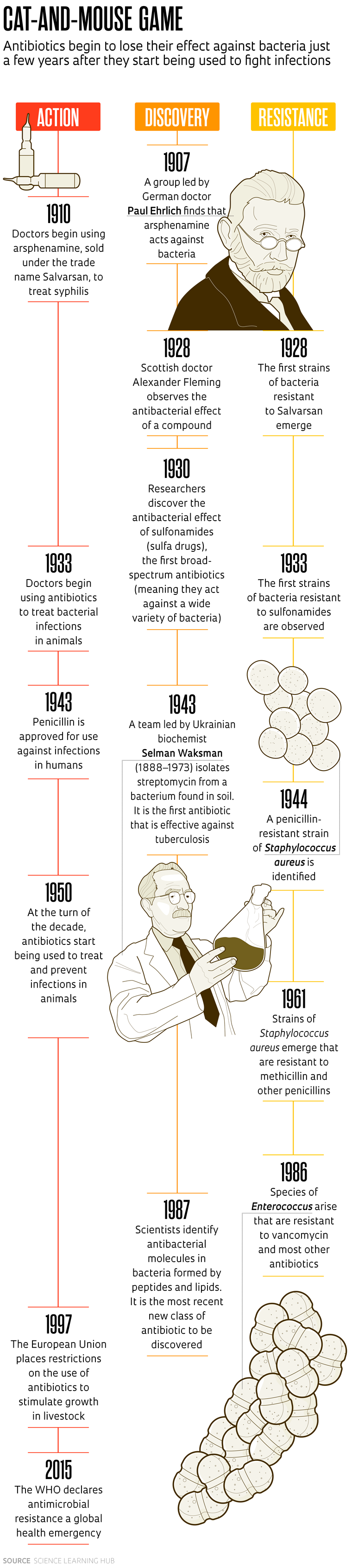

The first known synthetic antibiotic was arsphenamine, a compound containing arsenic that was identified by German doctor Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) in 1907, although there is evidence that treatments based on natural products had been used since ancient times.

In tests conducted on rabbits in 1909, Ehrlich and Japanese bacteriologist Sahachiro Hata (1873–1938) demonstrated that arsphenamine was capable of eliminating the bacteria that causes syphilis (Treponema pallidum) without killing the animals. Their work paved the way for the compound to be used from the following year onward—sold under the name Salvarsan—to treat the sexually transmitted disease, which humankind had been living with for centuries. In 1928, however, first reports started to emerge of cases where Salvarsan had no effect against some varieties of T. pallidum.

The same thing happened with penicillin. The compound was identified in 1928 by Scottish physician Alexander Fleming (1881–1955), discovered in a culture of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus that had been accidentally contaminated with a fungus of the genus Penicillium in his laboratory at Saint Mary’s Hospital, London. It was soon being used to treat infections. It would take more than a decade for other scientists to purify the active ingredient and implement large-scale production. However, even before the widespread use of penicillin saved the lives of thousands of soldiers in World War II, there were signs that bacteria could become resistant to the drug.

Fleming knew this and began calling attention to the problem, including in a speech he gave after winning the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1945. “It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them. There is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to nonlethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant,” said the Scottish doctor.

And that is exactly what has happened. The widespread use of these compounds in human and animal healthcare and agriculture has led to the emergence of bacteria resistant to various antimicrobials. “Fleming’s predictions turned out to be accurate: the incorrect use, sometimes real abuse, of antibiotics, speeds up the development and spread of bacteria resistant to them,” wrote Marco Terreni, a chemist from the University of Pavia, Italy, and colleagues in a review article on new antibiotics, published in the journal Molecules in 2021.

USDA-ARS

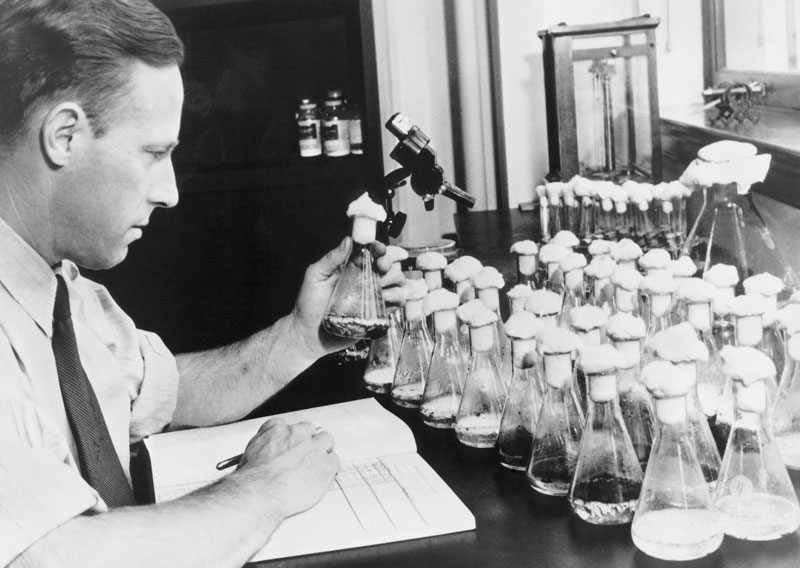

Andrew Moyer (1899–1959), who discovered how to mass-produce penicillinUSDA-ARS“It’s like a game of chess,” says biochemical pharmacist Ilana Camargo, head of the Molecular Epidemiology and Microbiology Laboratory (LEMiMo) at the University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos campus. Her group is characterizing bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics and identifying new compounds with the potential to combat them. Their most recent discovery is a synthetic derivative of plantaricin 149, a peptide produced by the bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum. During in vitro tests, the molecule eliminated 60 bacteria of different species and strains, each with varying degrees of resistance to existing drugs on the market, according to an article published in Antibiotics in February 2023. “Whenever we think we have a type of bacteria in check with a new antibiotic, it soon finds a way to escape,” Camargo says.

Dozens of new antibiotics have been identified since the turn of the twentieth century, from a wide range of classes and with many different mechanisms of action. A significant proportion of them—more than 75%, according to some experts—are of natural origin, produced by other microorganisms. For a long time, one of the champions at providing new antibiotics were bacteria of the genus Streptomyces. A review article published by British researchers in the journal Current Opinion in Microbiology in 2019 estimates that these bacteria, found in soil and decaying vegetation, were the source of 55% of antibiotics discovered between 1945 and 1978, including neomycin, streptomycin, grisemycin, and chloramphenicol. The problem is that bacteria almost always become resistant to new antibiotics soon after they are introduced to the market. In some cases, they become resistant to more than one antibiotic (see timeline on pages 19 and 21).

Until the late 1970s, major pharmaceutical companies worked around the issue by continuously launching new antibiotics, produced using molecules extracted from other bacteria or fungi and with different chemical structures. But as time went on, these compounds became ever harder to find in the most commonly studied microorganisms. “The lowest-hanging fruit had already been picked,” says Camargo, who works at the Center for Innovation in Biodiversity and Drug Discovery (CIBFAR), one of the Research, Innovation, and Diffusion Centers (RIDCs) funded by FAPESP. “It became necessary to invest in research into modifying the chemical structure of known molecules,” he explains.

The previous ease with which new antibiotics were obtained and their high performance created a false sense of security, alongside a major change that occurred in the pharmaceutical industry in the early 1980s. A new generation of managers were taking the helm at many large companies, redirecting investments toward the development of more expensive and profitable drugs to treat cancer and diseases associated with lifestyle, such as diabetes, explained Matthew Todd of University College London, UK, and colleagues in the journal Wellcome Open Research in 2021. “The central problem of the empty antibiotic pipeline is not scientific but economic,” they emphasized.

The amount of money companies made selling new antibiotics, which were more expensive and difficult to obtain, rarely covered the cost of development. And according to some experts, profits fell even further when generic versions of these medicines hit the market. “At the time, many major pharmaceutical companies shuttered entire departments and ended antibiotic screening and development programs,” says Brazilian biochemist Andréa Dessen, head of the Bacterial Pathogenesis Group at the Institute of Structural Biology (IBS) in Grenoble, France.