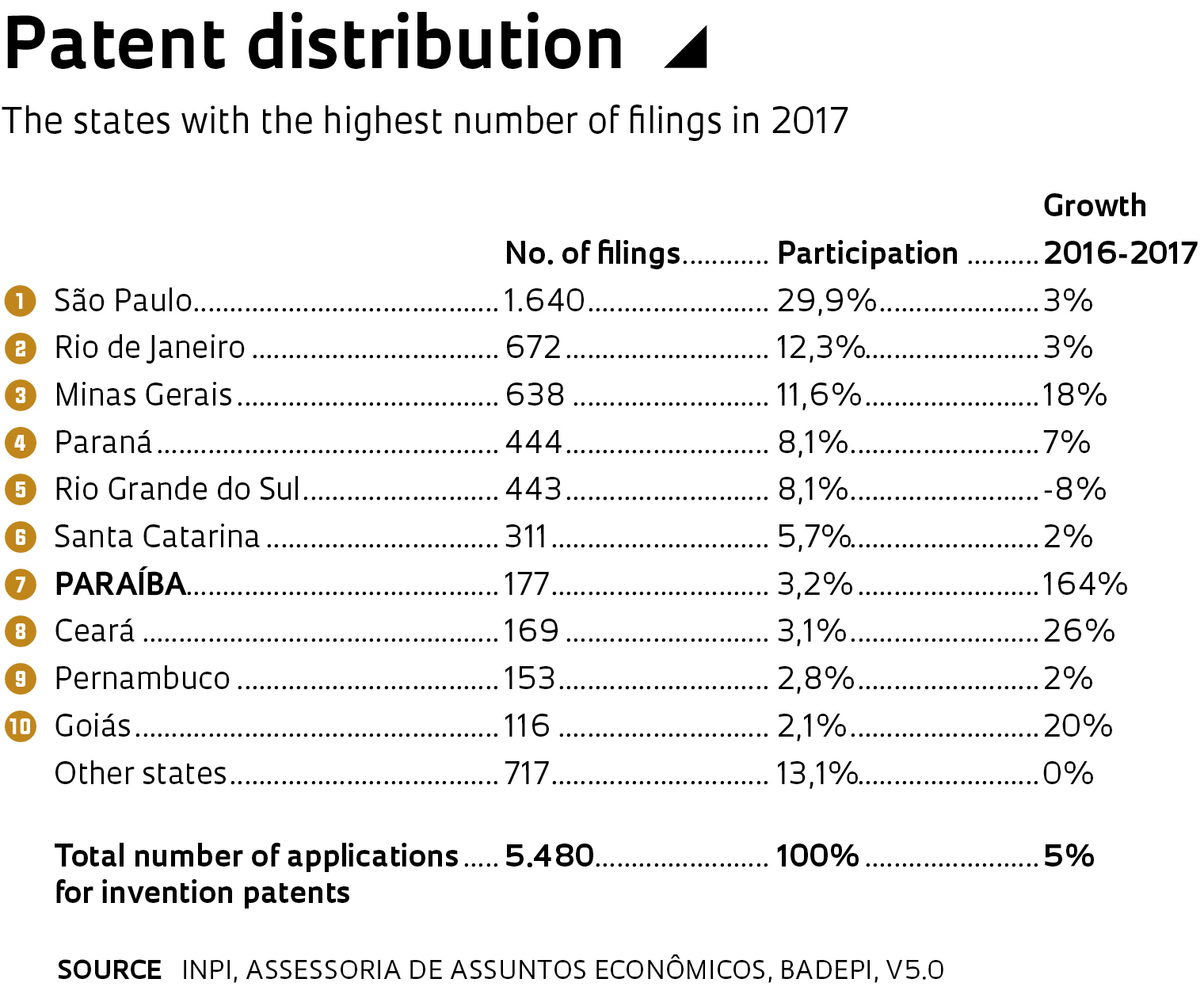

As one of the states with the best indicators set by the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI) for 2018, Paraíba recorded an increase of 164% in the number of patents filed between 2016 and 2017—the highest relative growth statewide. It holds the 7th highest ranking for patents filed, with a total of 177 filings in 2017, ahead of other northeastern states, such as Ceará (169) and Pernambuco (153). The top filers are the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), with 70 filings in 2017, and the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), with 66. The sum of these two Paraíba institutions surpassed the filings made by the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and the University of São Paulo (USP) together.

Their progress is the result of the establishment of the Centers for Technological Innovation at Paraíba universities over the past 10 years, helping to expand the culture of the protection of intellectual property in the state. Despite the increase in patent filings, there is still very little knowledge transfer to society through technology licensing by companies. Having expanded their portfolios of innovations with protected intellectual property, the institutions of Paraíba now face the challenge of deepening their relationships with the production sector. Inaugurated in 2013, the UFPB Bureau of Technological Innovation (Inova-UFPB) has 225 patents filed in the country that have not yet generated royalties for the university. “Many applied research projects are carried out in the academic arena without corporate partnerships. We attribute this to a lack of interaction with the production sector because patented technology can add value to products and processes,” according to chemist Petrônio Filgueiras de Athayde Filho, president of Inova-UFPB.

He adds that the fact that Paraíba does not have a strong industrial center makes technology transfer difficult. And he recognizes the importance of the university seeking partners, rather than waiting for them to spontaneously appear. “We began to present our patent portfolio to companies in other states,” says Athayde. Another objective for Inova-UFPB is to increase the university’s role as a business incubator. “We are going to encourage startups to take advantage of the technologies.” Recently, the center released a pre-startup call for proposals with the goal to begin licensing patents for emerging companies in 2019.

For researchers who own patents generated from UFPB, the innovation center’s work has made a tremendous contribution to communicating the importance of protecting intellectual property. However, they note that Inova-UFPB needs to focus now on promoting licensing. “There is considerable difficulty reaching the companies. We do not yet know how to build this bridge with the production sector,” confirms veterinarian Fabíola da Cruz Nunes, vice director of the Biotechnology Center at UFPB. “There is a need to actively seek partners from throughout Brazil and also from other countries.”

In partnership with The Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) Cotton Division in Campina Grande, the researcher developed and filed a patent request for an insecticide that fights the mosquito larvae Aedes aegypti through the leaf juice of the sisal (Agave sisalana), a plant that originated in Mexico and is cultivated in Brazil for fiber extraction. The juice attacks the intestine of the larvae and eliminates them completely. The idea is to offer larvicide in powder form for dilution in water, but toxicity tests for human consumption must still be carried out. “The goal is for a company to secure a patent and produce the insecticide, which is natural and biodegradable. If this patent has economic viability, it could help local sisal producers who lost market share due to the substitution of this plant by synthetic fibers in the industry,” notes da Cruz Nunes.

The patents filed by Inova-UFPB cover technologies in areas such as food engineering, fuel, chemistry, energy, and health. Athayde highlights innovations in new materials, such as shape memory alloys (SMAs), and in the development of electronic chips. “One of these technologies is an electronic baby monitor for people with a hearing impairment,” says Athayde. In the field of chemistry, there are patents for portable equipment to verify the quality of industrialized products and, in health, new molecules with the potential to treat diseases such as cancer, asthma, hypertension, and depression. But the area whose share of the Inova-UFPB portfolio continues to grow is that of food technology, which in 2017 was responsible for 32 patent filing applications for new products enriched with nutrients or probiotics.

Even though licensing has not yet reached a significant level in Paraíba, the increase in patent filings is a reflection of the consolidation of postgraduate programs in the state’s higher education and research institutions in recent years. A study carried out in 2015 by the Center for Strategic Studies and Management (CGEE) shows that Paraíba had 90 master’s programs and 42 doctoral programs in 2014, placing it as one of 11 states with the highest number of postgraduate programs in the country. Paraíba also placed 11th among all of the states in granting doctoral degrees that year. “UFPB alone held 76% of the master’s programs and 90% of the doctoral programs in Paraíba. This shows the extent to which the university is important for the state, something that all participants in the innovation system recognize,” says Ribeiro.

The licensing of technologies depends on promoting a culture of innovation among the universities, notes chemical engineer Nilton Silva, coordinator of the Center for Innovation and Technology Transfer (NITT) at UFCG, established in 2008. “Since 2016, various researchers from the institution have assumed responsibility for registering newly created technologies and learning to write patents,” he says. Silva notes that, in the first years of NITT-UFCG, the adopted strategy was to share knowledge about intellectual property at the university through courses and seminars. In September 2017, the center took a new step and launched the Observatory of Technological Intelligence. “It is an initiative to evaluate the potential of applying research projects and boosting patent licensing,” he adds.

According to Silva, the areas that generate the most new technologies at UFCG are electrical engineering and computer science—linked to the departments that raise the most funding for research and development (R&D). However, in terms of the number of patents granted, the fields that stand out are food engineering, chemical engineering, nutrition, and biotechnology. Nutritionist Ana Cristina Silveira Martins, along with her research group, holds a total of 30 patents, of which 28 were filed during her master’s in natural sciences and biotechnology at the Center for Education and Health at UFCG, Cuité campus. “I developed innovations using the mandacaru, a plant that is common in the Caatinga [semiarid scrublands],” explains the researcher, who is currently doing her doctorate at UFPB, where she holds two patents. One of the innovations is mandacaru flour with bioactive components, which can substitute wheat flour in making cakes and breads, as well as jelly, also made of mandacaru, added to passion fruit and goat’s milk yogurt.

“In order to make this jelly, various studies were carried out to standardize the product, along with in vitro tests and sensory analyses. It is an innovative formula and, for that reason, we patented it,” clarifies Silveira Martins. The researcher explains that the key motivation to work with mandacaru is to show the versatility of its fruit, which is used more for feeding animals. “We would like it to be consumed more by humans, as a food alternative for the northeastern region,” suggests the nutritionist, who has already presented workshops at the Federal Institute of Paraíba (IFPB) to train the residents of the municipality Princesa Isabel, in the back country of Paraíba, and produce and sell jellies made with regional fruits, such as maxixe. “Our goal is to license the innovations for the food industry.”

The lead role of the universities and public research institutions in the protection of intellectual property reflects the resilient nature of the Brazilian science and technology system, contrasting with industrialized countries where this role is mostly held by companies, and the universities do not hold a position of prominence in the rankings. The economic crisis seems to have worsened the problem in the country, with a decrease in the number of patents filed by corporations. In the same study by INPI, in which the universities of Paraíba are highlighted, there was only one company out of the 15 organizations that applied for the most patents in Brazil in 2017—CNH Industrial, manufacturer of farm equipment and light trucks. By comparison, during the period 2000 to 2005, eight companies were listed among the 15 most patented organizations in Brazil.

Paraíba has an innovation system that has continued to develop and mature over recent decades. In addition to four educational and public research institutions throughout the country—UFPB, UFCG, IFPB, and the State University of Paraíba (UEPB)—the government has public and private participants involved in the innovation process. In the municipality of Campina Grande, for example, the neighborhood Bodocongó has been identified as a technology hub, for having housed not only UFCG and UEPB facilities, but also technology-based companies, technical schools, and research support centers, such as the Paraíba Technological Park Foundation (PaqTcPB), which seeks to promote entrepreneurialism in areas such as software production, geoprocessing, and biotechnology.

The consolidation of the hub in Paraíba began in the 1970s, when Lynaldo Cavalcanti de Albuquerque, the then-chancellor of UFPB, implemented a strategy capable of attracting professionals from other states and training professors from Campina Grande. Researchers from well-known educational and research institutions, such as the Technological Institute of Aeronautics (ITA) in São José dos Campos (São Paulo State), settled in the Paraíba city where, in the 1980s, one of Brazil’s first technological parks was built.

“Paraíba has institutions focused on innovation, but one problem is that these participants do not interact among themselves,” according to accountant Fabiano de Moura Ribeiro, member of the Budget Committee for UFPB, and who is currently doing his doctorate at the University of Aveiro in Portugal. In 2017, he defended his master’s thesis in which he characterized more than 15 actors in the Paraíba innovation system, including educational and research institutions, corporate entities, and government bodies. These institutions—which include SEBRAE-Paraíba, the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Paraíba (FAPESQ), and EMBRAPA, as well as public universities—operate in various statewide municipalities, covering four mesoregions: Paraíba Forest, Paraíba Wild, Borborema, and Paraíba Back Country. “These institutions are very well distributed throughout the state, considering the demographic density of the region. However, this coverage could bring greater benefit if they were more connected with the other actors in the innovation system, primarily the entities representing the production sector,” observes Ribeiro.

An initiative announced in 2017 seeks to fix this problem, according to Ribeiro. It is called the Plan for Economic, Social and Sustainable Development for the Local Productive Cells of Paraíba (PLADES), comprised of higher education institutions, representatives from the business sector, state government, and the Superintendency of Northeastern Development (SUDENE). The objective is to build a strategy for territorial development in networks of local productive cells (APLs)—which have the capacity to stimulate interaction between the actors of a region with a view to sharing knowledge, consolidating productive structures, and creating the dynamism necessary to produce innovation. For Ribeiro, the strengthening of the APLs in the state could improve patent licensing. “Once research institutions, local communities, and companies are connected, it will be possible to identify research needs and offer solutions,” he argues.

Republish