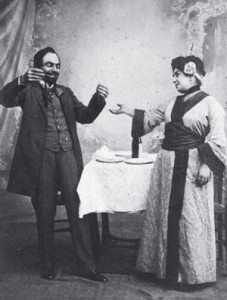

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK A REVISTA NO BRASILThe magazine Illustração Brasileira gives tips on how to dress for the theater, in 1909REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK A REVISTA NO BRASIL

Somewhere between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: dead children, before being buried, were often dressed like little Roman soldiers, so that, according to religious beliefs of the time, they would arrive in heaven ready to fulfill their role as guardian angels. When families went to the beach, women wore long skirts and carried parasols, while men wore trousers, shirts and hats. And as they walked along the streets of a São Paulo that was growing like crazy, salesmen of household articles adapted Paris fashions for a day-to-day life in the sun. These are just three clippings from a vast memory that Brazil has still not really brought out of the closet.

What individuals used to wear in the past can give new insights about the identity of a people, with clues scattered throughout families’ photograph albums, museum paintings, notebooks of drawings, literary texts and old magazines. These types of records are the main sources for Professor Fausto Roberto Poço Viana, from the Scenic Arts Department at the University of São Paulo’s Communication and Arts School (ECA-USP). Since 2007, he has conducted a detailed search of images and texts that might establish a link between garments and customs.

The period chosen for the study was 1889 to 1930, which respectively represent the beginning and the end of the Old Republic. The title of this paper is As tramas do café com leite [The threads of coffee with milk], in reference to the consequences of the well-known system whereby the presidency was swapped back and forth between the dominant states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo. The aim is to extend the research project back to include even earlier periods.

The transition from an essentially agrarian lifestyle to one that was taking its early steps towards the fever of urbanization determines some of the features of this portrait. However, the appreciation of the fashions that came from France, and in the case of the men also of the so-called English style, more than anything else, led to the spread here, particularly among the elite, of a style of dress akin to the European one.

For Viana, this importing of clothes does not mean that Brazil had not created its own identity. “I don’t think that the fact that people brought clothes from France necessarily implies the loss of a national identity. To the contrary, if someone says that we lost our local color as a result of this, I say, wait a minute, if that’s true, then we lost it five hundred years ago.”

Viana explains that a large part of the clothing and the reproduction models were brought by foreign tailors and dressmakers, as well as by a moneyed elite that would go shopping in Paris. “Even today I have a hard time understanding how these people could put up with wearing these clothes here in the tropics,” he says, in reference to the fact that the styles were basically created for colder winters.

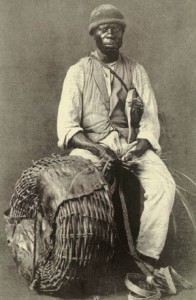

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK O BRASIL DE MARC FERREZBasket-maker, in Rio, in 1875REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK O BRASIL DE MARC FERREZ

Either way, the products that were imported were adapted. A photo taken in 1905 and that is part of the researcher’s collection shows in its foreground two young women walking along arm-in-arm, while in the background is the Largo da Misericórdia square. One of the young women is wearing a skirt that shows her ankles. “This would have been a minor scandal back then,” says Viana. “They are walking along the road arm-in-arm, alone, there’s no man accompanying them, and they’re playing around. They’re showing that the next generation is going to introduce novelties,” he interprets.

Too short a skirt

In the same photograph, Viana picks out one detail. There are folds at the bottom of one of the young women’s skirts. “As they grow they’ll let down these folds so that the skirt doesn’t get too short,” he explains. This practice, he goes on, became common at a time in which clothes were regarded as property, even being passed down from the grandparents.

Kathia Castilho, President of the Brazilian Association of Studies and Research into Fashion, who has a PhD and a master’s degree in communication and semiotics from PUC-SP, says that by recovering this type of memory, As tramas do café com leite fills in some of the numerous gaps in this subject. “Fashion and attire in Brazil are still unknown subjects; there’s a shortage of research, particularly about much earlier periods.”

The step-by-step approach used to undertake the study should help provide references for future projects, points out Castilho. “It reveals places, museums, libraries and publications that may, later on, motivate those who are interested in this type of knowledge,” he suggests.

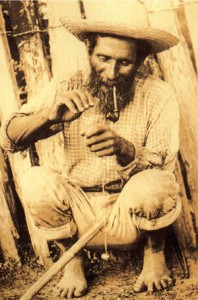

Among the main sources used by Viana are USP’s Museu Paulista (Paulista Museum), the Museu de Itu (Itu Museum), the Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro (the Rio de Janeiro National Library), the Army’s Documentation Center, in Rio de Janeiro (for research of military articles) and the archives of the Catholic Church’s Governing Body for the Metropolitan Region of São Paulo (for research of religious clothing). Photographs are always precious allies, with highlight going to the works of Marc Ferrez (1843-1923), Militão de Azevedo (1837-1905) and Guilherme Gaensly (1843-1928). Paintings also provide information, such as the picture Caipira picando fumo (Country yokel cutting up tobacco) (1893), by Almeida Júnior (1850-1899), which nowadays belongs to the collection of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (Fine Art Museum of the State of São Paulo).

Outside of academic circles, the study could also shape a legacy, supplying materials for the clothing market. “Fashion is always cyclical. It’s always reframing a particular value, updating historical values. Learning about our history is a worthwhile thing,” concludes the researcher.

However, Viana reiterates that it is not really fashion that he is studying. “I study garments. Fashion is everything that results from the sales process on an industrial scale. Fashion is related to a production model. What interests me is what people wear, not necessarily fashion,” he explains.

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK O BRASIL DE MARC FERREZA pair of Rio de Janeiro newspaper boys, in 1899REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK O BRASIL DE MARC FERREZ

In other words, in addition to the cutting and sewing manuals of the period, Fausto is interested in the carefree style of a rural worker who has his trousers rolled up to avoid burrs, as can be seen in a photo from 1911 published in the book Lembranças de São Paulo (Memories of São Paulo), by Carlos Cornejo and João Emilio Gerodetti (Studio Flash Produções Gráficas, 1999).

In the collection that he has put together, the poor are almost always barefoot. Moreover, when they are wearing shoes, often the same shoes can be seen in another photo on somebody else’s feet, which leads to one conclusion: some articles were only lent so that the person could pose for the picture being taken. The same thing happened with bags and parasols.

In order to retrieve images of black people, the research follows different paths. Even back in the nineteenth century a few photographers who set up shop in Brazil specialized in taking photos of slaves, not necessarily in order to document a reality. “They sold pictures of what was considered to be exotic outside Brazil. It is very clear, in some photographs, you see slaves in a state of depression… They understood what was happening to them.”

There are also records of slaves dressing up as aristocrats. In these cases, the clothes were also lent by their masters solely for the purpose of taking the picture. However, there are cases of families that managed to prosper after the so-called Golden Law of 1888 (which abolished slavery) and they are shown later on, in formal attire.

Viana’s research resulted from his interest in a related topic. He had already undertaken a major study of stage clothing, particularly theater costumes, for his master’s degree, which in the same way as with As tramas do café com leite, was financed by FAPESP.

The study O figurino que surge através do trabalho do ator – Uma abordagem prática (The costume that emerges from the actor’s work – A practical approach) and other projects related to this theme ended up supplying a specific theme within the current research for As tramas do café com leite, which is broken down into the following topics: theater costumes, regional garments, garments for playing, for socializing, for professional activities, and underwear.

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK LEMBRANÇAS DE SÃO PAULOCountry hick lights a pipe (1911)REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK LEMBRANÇAS DE SÃO PAULO

This classification follows the principles of work set out by the Portuguese Institute of Museums, consulted by Viana in 2010, during his doctorate in Museum Studies, which he did at Lisbon’s Lusófona University of Humanities and Technology. Fausto adds that the last item in the classification (that of underwear) caused him extra difficulties, mainly because, by habit, underwear was either used until it fell apart or it ended up in the trash can.

However, there is one extremely rich source for retrieving more intimate memories: the erotic post-cards, which, at that time, were mainly sold in brothels. “I am lucky in that, back in those days, this sort of material never showed the woman totally naked,” says Viana. “The woman was always photographed with underwear,” He adds.

The postcards were sold on the quays in the port area and testify to the country’s reputation: “The idea that we are the country of delights, and that Brazil is a country of sexually promiscuous people, where you went to enjoy a very active sex life, is much older than people assume. Pero Vaz de Caminha [a clerk with Pedro Álvares Cabral’s fleet] was himself enchanted to find naked women here,” states Viana.

Religious attire is also looked at, with special attention being given to the garments prescribed by the codes of the Catholic Church, although the research includes reference from the full range of religions – from candomblé [Afro-Brazilian religion], for instance. Fausto describes how the clothes of the church were established in the 1100s and have not changed up to now, with very few exceptions. For example, in Brazil, the pink colored garb is not used at Easter, as it is in Portugal.

There are clothing patterns that give clues about the origins of each piece. Some embossed clothes, for instance, indicate the use of a technique developed in France. The designs were cut out in cloth, applied to the garment and, then to finish off, were embroidered, resulting in texture.

The photo of a raincoat provides a perfect illustration of this type of technique. It also reveals, on account of a cloth hanging on the back of the item in question, that priests used to go out into the streets in the rain to bless the faithful. This material functioned as a cover for the head, but with the passing of time, it ended up losing its function and was used for decoration instead.

Times of mourning

REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK IMAGENS DO TEATRO PAULISTAScene from the play “Rússia e Japão” (Russia and Japan) in 1900REPRODUCTION FROM THE BOOK IMAGENS DO TEATRO PAULISTA

Another photo from Viana’s collection shows the family of the landowner Veridiana da Silva Prado (1825-1910). A son who died is represented by a photograph placed in a picture frame, together with the family. In addition, Veridiana is in the foreground wearing a heavy black dress. “When a child died, the mother was in mourning for the rest of her life. This was only relaxed after the 1930s, when the period of mourning was reduced,” explains Viana.

This type of picture does not really reveal what clothes were used on a day-to-day basis, as it was dependent upon a series of preparations. In other words, one got dressed up like that especially to take the picture. Snapshots, such as that of a group visiting a train station that is being built, are of greater value to Viana. “In this picture [he indicates the men who are standing in front of the construction] we can see that these are their everyday clothes. But you can clearly see that none of these people are poor,” says Viana ironically, referring to the wealth of options used by the more comfortably off.

During the period covered there is a historical event that led to a series of changes. With the start of the World War I, trips abroad became scarcer. In addition there was a drop in the imports of materials, which had previously come mainly from England and France. As a result, one began to see a change in the weight of the clothes in Brazil, as they took on lighter contours. For example, in the 1920s, some women began to walk around in the streets showing their arms and part of their legs.

To conclude his research, Viana intends to organize an exhibition with replicas of historical garments using similar materials. This is a format that he has already experimented with for Trajes em cena, which led to a display of costumes at São Paulo city’s Municipal Theater in 2004, with reconstitutions of historical pieces from the twentieth century.

During his research for As tramas do café com leite, Viana came across, in Rio de Janeiro’s National Museum, records that had been made by a researcher called Maria Sofia Jobim Magno de Carvalho (1904-1968), which consisted of a series of bound folders containing a substantial amount of material on garments. Maria Sofia belonged to a family of aristocrats, became a teacher and founded a school of feminine arts, the Imperial College, in Rio de Janeiro, where she was the principal for 20 years. Using the artistic name of Sophia Jobim, she dedicated herself to a study that linked subjects related to art, education, garments and customs.

Sophia studied at the Carnavelet Museum in Paris, at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and at the Benaki Museum in Athens. She researched byzantine art at the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens. She also worked as a clothes designer for cinema, such as for the 1953 film Sinhá moça (The Landowner’s Daughter), produced by São Paulo’s Vera Cruz Studio. During the course of her many trips across Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas she collected antique pieces, jewelry, objects of personal use, as well as typical and regional garments. “She was a highly skilled designer, and was very careful and thorough in her records,” says Viana.

The designs and texts that she assembled in her files will now provide material for new research by Viana. Some rare items do not correspond at all to the period portrayed by As tramas do café com leite and to the restrictions of talking about garments in Brazil. Also given the sheer volume and wealth of material, all of this has resulted in a separate project, Cadernos de Sophia (Sophia’s Notebooks), which proposes a review of this collection.

The Project

The fabric of coffee and milk (nº 2006/057161-2); Modality Regular Funding for Research; Coordinator Fausto Viana – USP; Investment R$ 95,636.00 (FAPESP)