Julia D’OliveiraOver 250 million years ago, an ancestral reptile would have heard the buzz of insectsJulia D’Oliveira

For a lizard to survive in a dark, smoky environment with a scarcity of food, as was Earth between around 250 million and 200 million years ago—a period marked by two mass extinction events—a good ear was essential. With it, the reptile could hear prey and predators better or even practice vocal communication with members of the same species.

The tympanic membrane, a film that moves when it comes into contact with sound waves, was an evolutionary addition that increased the sound spectrum detected by reptiles. This small part of the auditory system in birds, alligators, crocodiles, snakes, lizards, and turtles was fundamental for these animals to survive and proliferate throughout evolutionary history, according to an article published in October in the journal Current Biology. The study includes birds because, evolutionarily, they share the same common ancestor as reptiles.

The research has implications in an important dilemma in evolutionary biology. “There is a great debate about the evolution of hearing in reptiles: if it emerged independently in various groups or from a single ancestor,” says paleontologist Mario Bronzati, a Brazilian researcher doing a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Tübingen, in Germany, and the lead author of the article.

The debate between hypotheses was intensified by the size of the group of reptiles, which today has more than 20,000 species, and by the lack of studies focused on the evolution of hearing in this group. “Many studies have focused on model animals, such as chickens and mice,” says Bronzati. With this differential, the results outlined in the recent article suggest that hearing arose from a single event and was inherited by the descendants.

The researchers came to these conclusions by means of the study of reptile fossils and embryos, in a combination of two fields of knowledge: paleontology and evolutionary developmental biology, which studies embryology from an evolutionary perspective and is referred to as evo-devo by researchers.

“We would not have been able to answer all the questions we did without this combination,” explains biologist Tiana Kohlsdorf, from the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto School of Philosophy, Sciences, and Languages and Literature (FFCLRP-USP) and coordinator of the study. “Through fossils, we can infer an older timescale that includes the common ancestor, and the development over a period of life, from embryos, allows us to see how the membrane develops in living reptiles.”

The analysis of the embryos is also important because the tympanic membrane is a soft tissue, which is not preserved in fossils. Even the bony characteristics associated with hearing are variable and do not always serve as a clue, as seen with a small shell-like structure on the skull of lizards that does not exist in alligators.

“The authors approach the question from an innovative angle,” says Brazilian paleontologist Gabriela Sobral, of Stuttgart Museum in Germany, who did not participate in the study. In 2019, she published an article in the journal PeerJ about the identification of the eardrum in the ancestral lineage that would have given rise to crocodilians and birds. “The article shows how the main characteristics used to identify tympanic hearing in fossils, the shell-like structure, is a condition specific to snakes and lizards.”

“Paleontology and evo-devo complement each other: one field provides the other concrete examples of what is factually possible within an almost infinite universe of possibilities,” adds Sobral. “The article shows how paleontology is a fundamental part of understanding the evolution of life on Earth.”

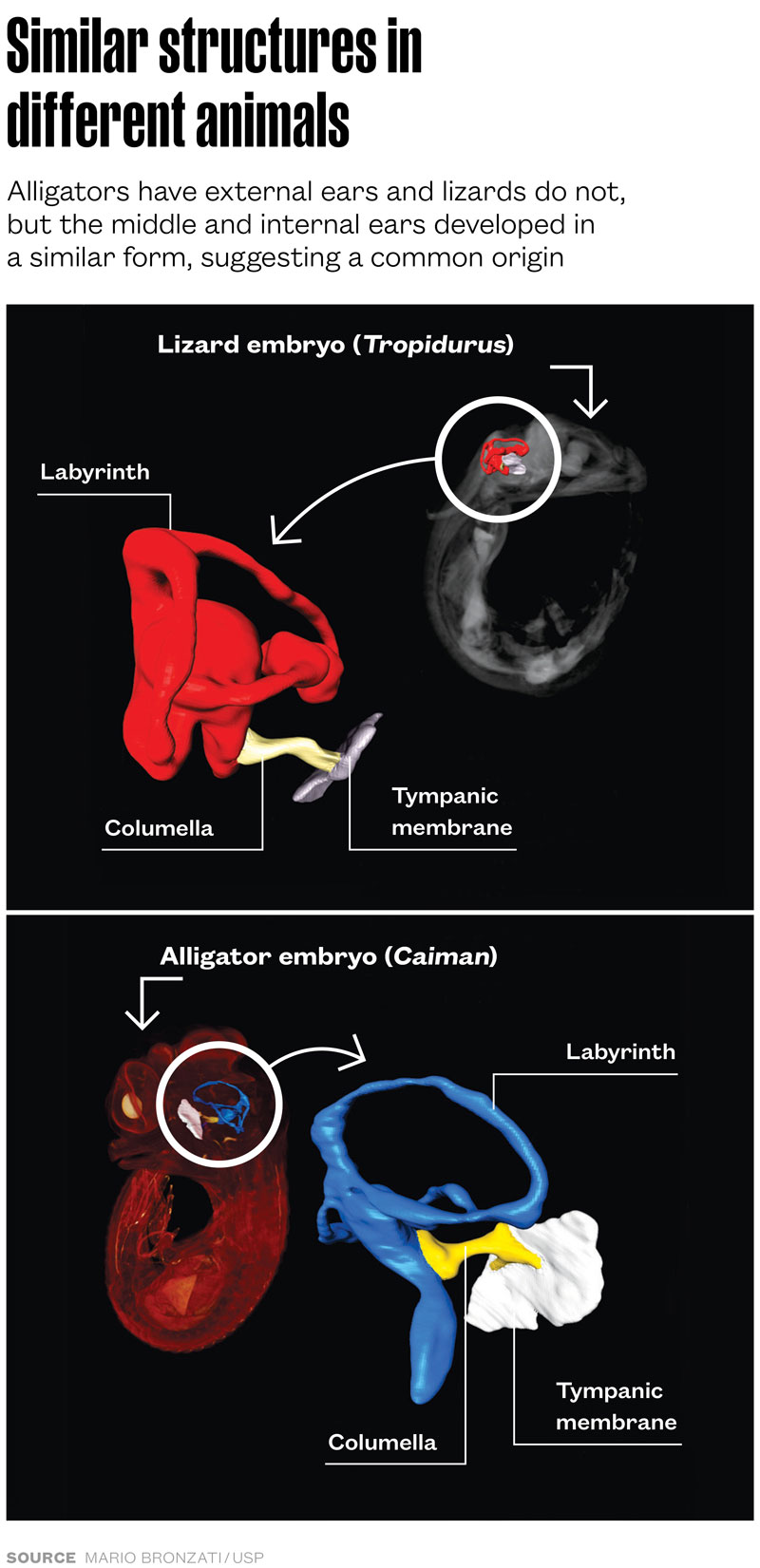

One part of the research was to compare embryos of lizards (Tropidurus) and alligators (Caiman). The researchers collected the eggs from an urban environment in the city of São Simão, in the countryside of the state of São Paulo, in the case of the lizards, and from the Caimasul alligator farm in Corumbá, Mato Grosso do Sul. “It was a real challenge, we were still in the period of the pandemic,” recalls Bronzati.

In the laboratory, the team carefully opened the thin shells of the eggs to examine the baby alligators and lizards, still immersed in the aqueous solution that forms the amniotic fluid. Using microscopes, tomography devices, and traditional tissue examination techniques, the researchers found that the process of tympanic ear formation was very similar in both animals. The same would be the case for bird embryos.

“In all of these animals, the tympanic cavity forms from the extension of the pharyngeal cavity, which is connected to the throat,” explains Bronzati. “And the tympanic membrane arises in a region called the second pharyngeal arch.” According to Kohlsdorf, another important point is that “although we see this similarity between birds, alligators, and lizards, the development is different in mammal embryos, with the formation of the tympanic membrane arising from the first pharyngeal arch.”

“This all becomes even more intriguing when we note that several extinct relatives of reptiles did not have tympanic hearing,” adds Bronzati. “We believe that the evolution of this trait favored the survival of the group, especially considering the mass extinction events.”

Two of these extinction events marked the crucial period for the emergence of tympanic hearing. The first, 250 million years ago, occurred during the Permian period and wiped out over 95% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial species. It is unknown what exactly caused the extinction, but the possibility involves a combination of climatic changes and volcanic eruptions. Similar factors led to a new catastrophe 50 million years later, between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, with the extinction of 80% of the planet’s species.

In Sobral’s opinion, further investigation is needed into the origin and development of the middle ear cavity and the related structures. “These issues have only recently been analyzed in mammals, but they are still unknown in reptiles.”

Other answers reside in genetics. “We don’t know whether the genes that form the tympanic membrane in chickens and other animals are the same,” says Bronzati. There is still the need to investigate the loss of parts of the auditory system in some reptiles, such as serpents, which lost the tympanic membrane, and some lizards. “It is an article that opens doors to new areas of research,” concludes Sobral.

The story above was published with the title “Warning sound to escape extinction” in issue 345 of November/2024.

Projects

1. Ecology, evolution, and development (eco-evo-devo) in Brazilian herpetofauna (n° 15/07650-6); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Tiana Kohlsdorf (USP); Investment R$1,261,130.44.

2. Evo-devo in dynamic environments: Implications of climate change on biodiversity (n° 20/14780-1); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Biota Program; Principal Investigator Tiana Kohlsdorf (USP); Investment R$3,229,900.69.

3. Filling gaps in our understanding of Crocodylomorpha macroevolution using comparative methods (n° 22/05697-9); Grant Mechanism: Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Max Cardoso Langer (USP); Beneficiary Pedro Lorena Godoy; Investment R$88,743.56.

Scientific articles

BRONZATI, M. et al. Deep-time origin of tympanic hearing in crown reptiles. Current Biology. Vol. 34, pp. 1–7. Oct. 2024.

SOBRAL, G. et al. The braincase of Mesosuchus browni (Reptilia, Archosauromorpha) with information on the inner ear and description of a pneumatic sinus. PeerJ. Vol. 7. May 2019.

Republish