The primary source of information on the religious affiliations of the Brazilian population is the Demographic Census, which is conducted every 10 years by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). However, this interval is too long for sociologists and other researchers of religion. The evangelical population in Brazil has grown rapidly since the 1960s, with Census data quickly becoming outdated.

“There is much talk about the evangelical population increasing in the country, but we don’t know exactly how this has been happening, nor where this growth began, for example,” notes Brazilian political scientist Victor Araújo of the UK’s University of Reading. He continues, “The Census is a snapshot, and we do not have dynamic data on what happens between these IBGE surveys.”

While 90% of Brazilians self-declared as Catholic during the 1960s, evangelicalism, with its different denominations, is set to become the country’s largest religious group by 2040. The phenomenon that Brazil is currently experiencing is known as “religious transition.” The same phenomenon was widespread in parts of Europe during the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, but in Brazil, according to Araújo, the process may take less than 100 years.

To identify how evangelical churches are distributed across the country, Araújo drew on another source: data from the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service (SRF), which are available online. Since there are more than 152,000 religious establishments registered in Brazil, this political scientist has developed an algorithm in the programming language R that has open-source code and is accessible to researchers and others interested in the topic.

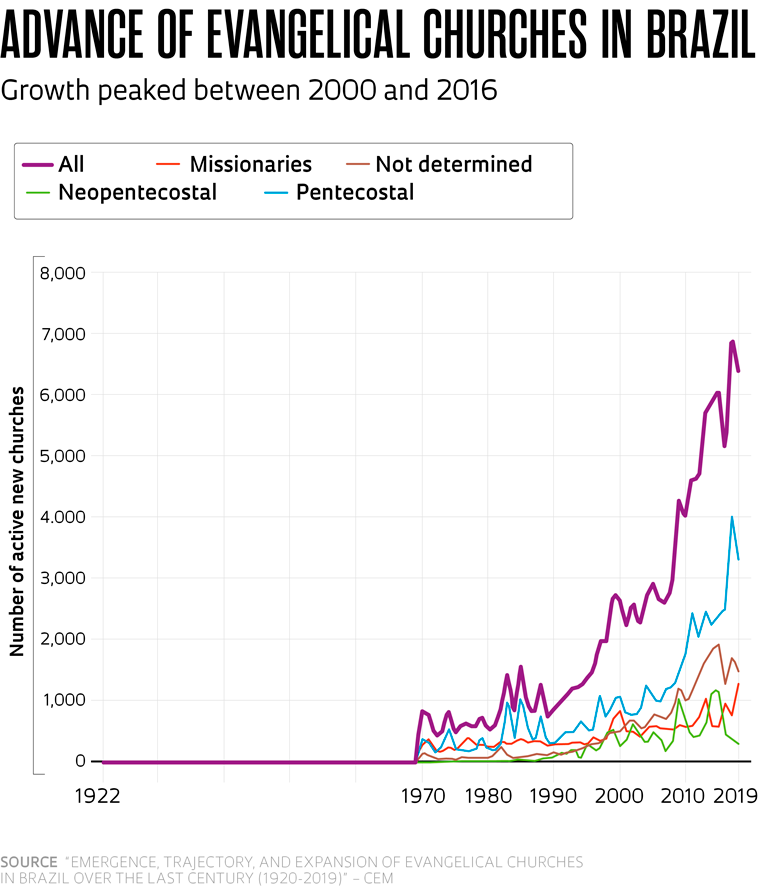

This method enabled the detection and classification of temples registered with the SRF in line with IBGE census categories: missionaries, including typically older churches, such as Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist; Pentecostals, whose doctrine includes elements that the Missionaries do not, such as belief in miracles, and include Assembleia de Deus (Assembly of God), Congregação Cristã do Brasil (Christian Congregation of Brazil), and Deus é Amor (God is Love); and Neopentecostals, a group that emerged in Brazil at the end of the 1970s, focuses on the theology of prosperity and includes churches such as Universal do Reino de Deus (God’s Kingdom Universal), Sara Nossa Terra (Sara Our Earth), and Renascer em Cristo (Rebirth in Christ). Other churches are listed as “classification not determined.”

The results were published in the technical note “Emergence, trajectory, and expansion of evangelical churches in Brazil over the last century (1920–2019),” which was recently published by the University of São Paulo’s Center for Metropolitan Studies (CEM-USP), with which Araújo is associated in Brazil. The CEM is one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) that are funded by FAPESP. “The survey provides researchers in this field with an additional datum because the IBGE Demographic Census says nothing about the creation of places of worship,” says sociologist Ricardo Mariano of USP’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH-USP).

Using this digital resource, the researcher mapped out Brazil’s religious transition background between 1920 and 2019. Araújo notes that the legislation on churches has been amended several times, but the oldest record still active at the Federal Revenue Service is from 1922 and involves a Baptist church in Nova Iguaçu (Rio de Janeiro State). As expounded in the technical note, this does not mean that this was the first evangelical church inaugurated in Brazil. For example, historical records indicate the existence of a congregation of the Assembleia de Deus founded in 1911 in Belém (Pará State).

Following article 44 of the Civil Code, religious organizations in Brazil have had to hold a National Legal Entities’ (Corporate) Registration (CNPJ) since 2002, and this requirement is also provided for in Law no. 10.825/2003. “The legislation states that churches are private legal entities. Therefore, they must be registered with the Federal Revenue, and, in turn, the CNPJ, to enable them to open bank accounts and hire employees, for example,” says Armando Rovai, chair of the Special Business Advocacy Commission of the Brazilian Bar Council, São Paulo branch (OAB-SP). Created in 1998, the CNPJ system was preceded by the General Taxpayers’ Register (CGC), which was instituted in 1964.

Léo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESPA small congregation in Rio de Janeiro; many do not register with the Federal RevenueLéo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Araújo sees this religious transition as “one of the most important demographic phenomena in modern Brazil.” The process gained pace mainly from the 1960s, with the urbanization and industrialization of the country. “When people migrated to the new city limits, there were not yet Catholic parishes in place. The evangelicals were first to arrive in these locations because they could open their places of worship without having to apply to the Vatican, as the Catholics were obligated to do,” recalls the researcher, who authored the book A religião distrai os pobres? O voto econômico de joelhos para a moral e os bons costumes (Does religion distract the poor? The economic vote kneeling before morals and good habits) (Edições 70, 2022).

To date, the most urbanized regions are the most sizeable bastions of Brazilian evangelism. Among the Brazilian states, Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro have the highest number of evangelical churches—more than 80 per 100,000 inhabitants across both states. In other words, these locations have an evangelical church for every 1,250 residents, as revealed in the survey. Northeastern Brazil remains widely Catholic, although evangelicals predominate in state-capital metropolitan regions.

The anthropologist Ronaldo de Almeida, who is the coordinator of the Laboratory of Religious Anthropology at the University of Campinas (LAR-UNICAMP), says that Araújo’s plotting of these temples corroborates aspects that religious studies have been attempting to demonstrate in recent years. One of these aspects is the accelerated growth of evangelism in the 1980s, when the Census began indicating the presence of this group in the country more accurately.

Another aspect is the territorial expansion of these churches that was revealed in the 2000 Census. “You can see the growth of evangelical churches in areas of recent immigration,” adds Almeida, also a researcher at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP). They continue, “The North and Midwest regions, frontiers of agricultural expansion in recent decades, received many farmers from the South, where the protestant presence is historically strong.”

Léo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESPThe Universal Church’s Temple of Solomon, in the São Paulo neighborhood of BrásLéo Ramos Chaves/Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

The first churches that were set up, along with the migrants, were missionary in character, but in the last decade, Pentecostal and Neopentecostal churches have advanced more quickly, as exemplified by the northern state of Rondônia. According to the map’s ranking of states with the highest numbers of evangelical churches, Rondônia occupied third-to-last place in 1970 but began to feature among the top five in 2000. In 2019, Rondônia was home to 60 temples per 100,000 inhabitants and was one of the Brazilian states closest to completing the religious transition alongside Rio de Janeiro, Mato Grosso do Sul, and Espírito Santo.

However, counting places of worship does not accurately demonstrate the numbers of these faithful in Brazil. After all, a chapel and a cathedral each have their own CNPJ registration, but their attendance capacities are incalculably different. Almeida notes, “As with all studies, there are limitations. It’s difficult to fathom the Brazilian evangelical expansion in the last century, but registration of temples is another variable that contributes to an insight into what has happened in Brazil over the course of this period”.

Furthermore, many churches operate clandestinely, with no CNPJ: a religious leader may, for example, hold services in the living room or garage of his or her house. As Mariano observes, “A lot of small congregations don’t feel obligated to formalize. Underreporting is considerable”. The survey does not include churches that opened during the period analyzed but, for some reason, were no longer active in 2019. Additionally, individuals can register church CNPJs for nonreligious purposes, but these are not identifiable in the SRF data, as Araújo warns.

Even so, the data corresponding to the Census years, such as 2000 and 2010, are aligned with the numbers published by the IBGE. Araújo notes, “For non-census years when comparison is not possible, it’s likely that the classification will be close to what it would be if the data were collected every year”.

For this political scientist, making the tool he developed available to other researchers is one of the aims of his study. He concludes, “Anyone with an intermediate knowledge of programming and a computer with standard processing capacity could replicate the procedures”. He plans to update the study as new data become available on the Federal Revenue Service website and to compare the results with the numbers to be published after the 2022 Census.

Project

Center for Metropolitan Studies (CEM) (nº 13/07616-7); Grant Mechanism Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs); Principal Investigator Eduardo Cesar Leão Marques; Investment R$21,233,150.42 (over a 10-year period).

Republish