In 1818, 10 years after it was established to print newspapers, books, or pamphlets, the Imprensa Régia produced the first book meant for primary school children: Leitura para os meninos (Reading for boys), containing “moral stories on the flaws commonly seen in tender ages, and a dialogue on geography, chronology, the history of Portugal, and natural history,” by military engineer and politician José Saturnino da Costa Pereira (1771–1852). At that time, a translation of Tesouro dos meninos (Boys’ Treasure) was already circulating in both Brazil and Portugal, containing “teachings on morals and good manners.” Published at the end of the 18th century in Lisbon, it was authored by French priest Pierre Louis Blanchard (1758–1829) and translated by Mateus José da Rocha (?–1828) of Portugal.

An entity that belonged to the royal government, the Imprensa Régia was also an instrument of censorship. Three different authorities would review the material to be published to ensure “that nothing was printed contrary to religion, the government, and good manners,” noted journalist Juarez Bahia (1930–1998) in his book Jornal, história e técnica – História da imprensa brasileira (Newspaper, history, and technique: The history of the press in Brazil) (Ática, 1990). These guidelines meant that the first schoolbooks in Brazil included mainly religious content and that many books were translated and adapted from French.

This only began to change in 1821, when the government ceased to be the official producer of books for primary education and private publishers took over this role, prioritizing Brazilian authors. French journalist Pierre Plancher (1779–1844) began this phase. In 1827, he published two titles through the publishing house Typographia Plancher-Seignot, in Rio de Janeiro: Compendio scientifico para a mocidade brasileira, destinado ao uso das escolas dos dous sexos (Scientific compendium for Brazilian youth, meant for use in schools for both boys and girls), organized by lawyer José Paulo de Figueirôa Nabuco de Araújo (1796–1863), who would soon become minister of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Empire; and Escola brasileira, ou Instrução útil a todas as classes, extraída da Sagrada Escritura para uso da mocidade (Brazilian school, or useful teachings for all classes, extracted from the Holy Scripture for use by youth), in two volumes, written by senator José da Silva Lisboa (1756–1835), the viscount of Cairu. The two books were the first in what is currently the best-selling genre in the nation.

Also in 1827—on October 15, which would later become Teachers’ Day—the government published the Law of the Schools of First Letters, which established teaching units in all cities, towns, and the most populous places in the Empire. “It was the first law about public education in Brazil, and it mentioned schools for both sexes, something innovative for the time. In these schools, students would learn to read, write, and count, but there were still no grades or separate subjects,” observes historian Circe Bittencourt, of the University of São Paulo School of Education (FE-USP) and founder of the Library of Textbooks and Special Collections and the Database of Brazilian Schoolbooks.

Escola Caetano de Campos Historical Archives /CRE Mario Covas /EFAPE /SEDUC-SP

A class of girls being taught math in 1908, in a São Paulo schoolEscola Caetano de Campos Historical Archives /CRE Mario Covas /EFAPE /SEDUC-SP“These textbooks initially prioritized the training of teachers, who used them to plan lessons,” says Bittencourt. She also states they were often written or edited by intellectuals and politicians; this was to make sure their content was approved by the Empire.

The Compendio (Compendium) featured nine lithography prints—a technique that involved a stone matrix. The pictures taught, for example, how to draw the human body. A companion text would note that women, compared to men, “have a smaller head, a longer neck, a raised chest, and wider and shorter kidneys and thighs.”

At 318 pages and adapted from French works, it covered the so-called liberal arts, such as grammar, poetry, writing, painting, sculpture, and drawing; the natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and natural history; and those considered abstract, such as mathematics, as well as areas such as law, agriculture, and commerce. “In some sections, the author writes about topics that were of interest to the school in the form of entries, with an educational approach. It was an embryonic version of a textbook,” says Bittencourt. Permeated by a religious tone, each subject is approached through questions and answers—the so-called catechetical method.

The Escola brasileira (Brazilian school), on the other hand, relies entirely on the Bible, including advice such as: “The hard-hearted shall be overwhelmed with evil at the end of life; and he who loves danger shall perish in it. The heart that walks two paths shall not succeed; and the depraved of heart shall find in them his stumbling block.” Senator Lisboa argued that the lower classes should read good books, containing teachings of morals and faith. This would protect them from ideas such as those that sparked the French Revolution (1789–1799), which they would be exposed to in case they read what he called “bad books.”

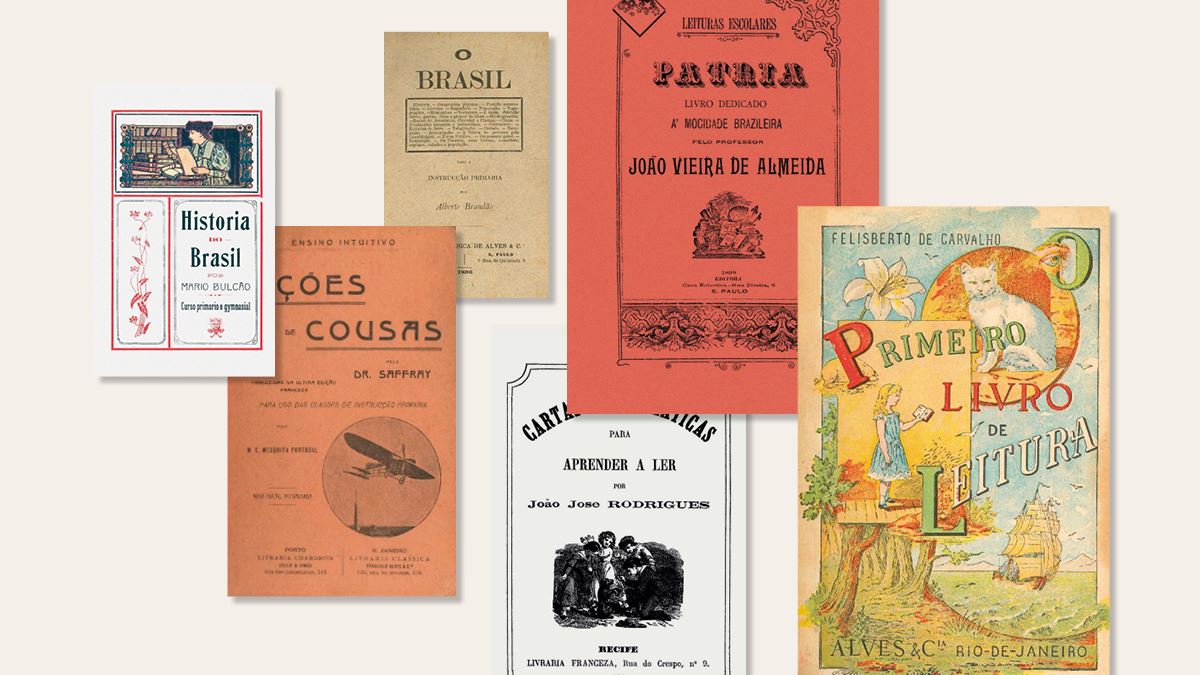

LEMAD /FFLCH /USP

Among books with various approaches, O livro do povo (The book of the people), from 1863, stood out and was a national best-sellerLEMAD /FFLCH /USPPrivate publishing houses took over both the production and distribution of the textbooks. “Schoolbooks became the main product of the Brazilian publishing market,” explains Bittencourt. In some provinces, the government would purchase and distribute the books, but they were usually bought by the families of the students.

Starting in the second half of the 19th century, more publishing houses came to Brazil, boosting editorial production. In 1885, 318 schoolbooks were circulating in the country, generally printed by local publishing houses. According to Bittencourt’s research for her PhD thesis, defended in 1993, three of them—Laemmert, Nicolau Alves, and Garnier—represented 44.2% of all published books.

Some of these books went on to become bestsellers. Printed in the state of Maranhão by the publishing house Typographia do Frias, the first edition of the 1863 book O livro do povo (The book of the people), with about 4,000 copies sold, rivaled novels of the time. In 1865, it reached its fourth edition. The cover alone reveals that the book was “used in primary schools of the provinces of Amazonas, Pará, Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, Paraíba, and Pernambuco.” Its author held a Bachelor of law, poet and Recife Law School alumnus, Antonio Marques Rodrigues (1826–1873).

“The fact that the author came from a prestigious university and had the approval of the church gave the book credibility,” notes historian Rozélia Bezerra, from the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE), who analyzed the piece for her PhD research, completed in 2010. She believes its “accessible language explains its success, in part.”

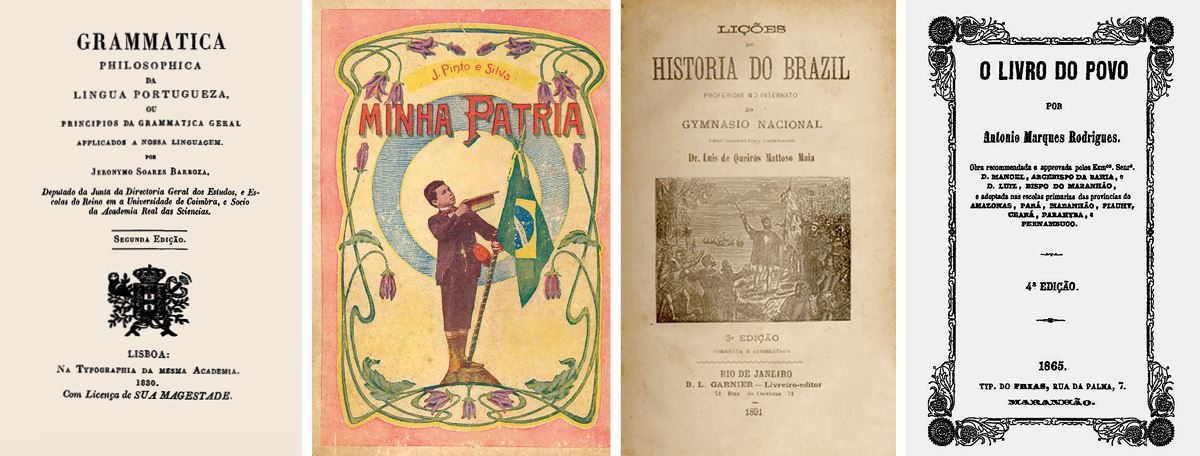

Federal Senate Digital Library

Instructions from the Compendio scientifico para a mocidade brasileira (Scientific compendium for Brazilian youth), 1827, on how to draw the human bodyFederal Senate Digital LibraryThe first section concerned religion; the second, various subjects, such as geography, moral education, fables, and health. Animals were given human characteristics: the donkey, for example, “is humble, long-suffering, and quiet, while the horse is impetuous, haughty, and ardent.” The lessons on hygiene were based on a mix of popular sayings and moral teachings, such as “early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise,” or “the boy that raises his voice hurts his throat.” “In choosing sayings that rhymed, the author made them more sonically appealing, which mattered because this content was often read aloud to students, since there were not enough books for everyone,” notes the UFRPE researcher.

When new subjects were included in the school curriculum, such as geography and Brazilian history, the need arose for more local content, developed by local authors. Bittencourt cites two of note: general José Inácio de Abreu e Lima (1794–1869), author of the 1843 Compêndio de história do Brasil (Compendium of Brazilian history), and novelist Joaquim Manuel de Macedo (1820–1882), who was also a teacher and wrote Lições de história do Brasil (Lessons on the history of Brazil) in 1861.

At the end of the 19th century, teachers from prestigious schools, such as the Imperial Colégio Pedro II, founded in 1838, in Rio de Janeiro, began publishing textbooks, which were then used in other schools throughout Brazil. One of them was the Anthologia nacional (National anthology), published in 1895, meant for use in Portuguese classes. Authored by two professors, linguist and politician Fausto Barreto (1852–1915) and poet and politician Carlos de Laet (1847–1927), “the book contains selected texts by Brazilian and Portuguese authors and is innovative in its adoption of a reverse chronological order, prioritizing modern writers. The authors argued that it was important to know the present before learning about the past,” explains Marcia Razzini, languages and literature expert who analyzed the Anthologia in her PhD thesis, completed in 2000. The book had a long shelf life, with 43 editions—the last published in 1969.

“From the 19th century onward, textbooks were expensive to produce and difficult to distribute,” Bittencourt points out. “In public education, many students couldn’t afford them.” The 1937 founding of the National Book Institute was one of the first efforts to turn the production and distribution of these works into public policy, but it was not successful. Another initiative, the National Textbook Commission (CNLD), established the following year, also failed.

In 1966, the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), in collaboration with the National Union of Book Publishers and the US Agency for International Development, promised to distribute, at no cost, around 50 million textbooks throughout the country over a three-year period. “This is an embryo of what the National Textbook Program [PNLD] would have been,” says historian João Quaresma, a public policy consultant at MEC. The program would not be officially established until 1985.

In 2020, according to data from the National Fund for Educational Development website, the now-called National Book and Teaching Material Program purchased 172,571,931 copies for about R$1.4 billion. These were distributed to more than 32 million students in 123,342 public kindergarten, primary, and secondary schools.

Also in 2020, according to the National Union of Book Publishers, of the 314,141,024 books printed in Brazil, 52.94% were textbooks. The books are produced by private publishers following criteria established by the MEC. After they are assessed by experts, the approved books become part of a catalog from which teachers choose those they wish to use.

As part of his PhD research in history at the University of Brasilia, about the PNLD, Quaresma interviewed teachers who taught classes remotely in 2020 due to the pandemic. “Many said that the textbook has never been so important when planning lessons and activities during such an exhausting period of time we are living,” he shares.

Republish