On June 23, 1874, the front page of the Jornal do Recife newspaper celebrated the new development: “We are, now, in instant communication with the whole world, and just yesterday some private dispatches were exchanged with the London square.” The news referred to the arrival of the submarine telegraph cable that connected Carcavelos beach, 13 miles from Lisbon, Portugal, to Recife, the capital of Pernambuco, with connections in Madeira Island and Cabo Verde.

From the Brazilian city, the cable connected to the telegraph network, which saw its first developments in Brazil in 1852, along with the railroads. There was also already a submarine cable along the coast, operated by the Western and Brazilian Telegraph Company (WBTC). Immediately, international telegrams led to a surge in the flow of information. “It only took two hours to reply to a message. Without a doubt, a new era began yesterday in our country,” concluded the Recife newspaper.

Until then, journalists and readers in imperial Brazil waited 15 to 40 days to receive letters or newspapers from Europe, brought by steamship. “In 1874, for the first time, Brazilian newspapers could publish news coming out of Europe from the previous day,” says journalist Pedro Aguiar, of Fluminense Federal University (UFF), who studies the international news circulation system.

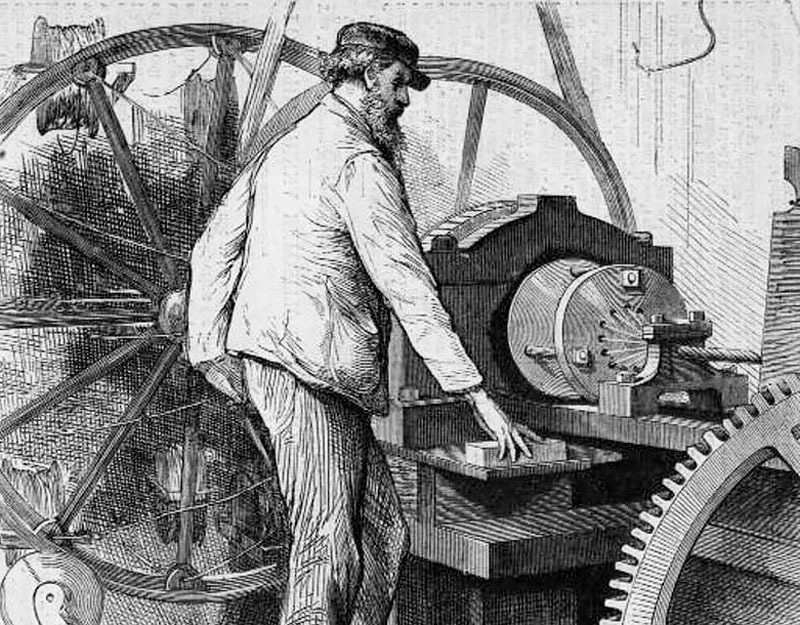

atlantic-cable.comIllustration showing one of the initial stages of cable production, in which seven copper wires covered in gutta-percha latex are braided and coated with iron wiresatlantic-cable.com

According to the researcher, at least since 1851 Brazilian newspapers had been getting news from international agencies indirectly, copied from foreign newspapers. “Even with the international cable, copying continued, because many newspapers couldn’t afford to subscribe to the agencies’ services,” noted Aguiar, who in February launched a website on the UFF portal about the 150-year history of news agencies in Brazil.

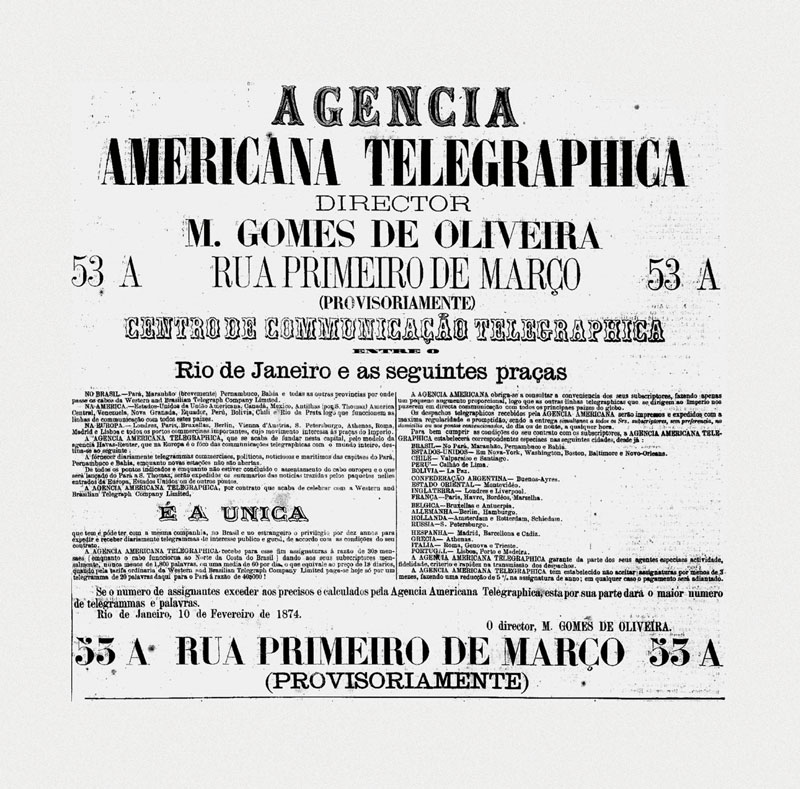

Installed and operated by the Brazilian Submarine Telegraph Company, the first submarine telegraph cable paved the way for national and international news agencies, which sold information to the press, investors, and coffee traders. Four months before the cable arrived, banker Manoel Gomes de Oliveira (date of birth and death unknown) opened Gomes de Oliveira & Companhia and inaugurated Agência Americana Telegráfica (AAT), which operated until 1875. The agency was created to disseminate news from Europe and the United States to newspapers in Brazil and to send Brazilian news abroad. Oliveira also founded a newspaper called O Globo (unrelated to the newspaper created by Irineu Marinho in 1925), which published his agency’s news and served as an advertising vehicle for AAT’s services.

Supported by a contract with WBTC, AAT guaranteed its subscribers at least 60 words a day for a monthly subscription costing 30 contos de réis, which was more affordable than WBTC’s subscription, says Aguiar. “A 20-word telegram to England cost the equivalent of US$94 at the time,” noted journalist Matías Molina in the book História dos jornais no Brasil (History of newspapers in Brazil; Companhia das Letras, 2015), based on an ad from July 7, 1874, in the Rio de Janeiro Jornal do Commercio citing WBTC’s price for telegrams to Europe.

National Library FoundationAd by Agência Americana Telegráfica, which ran in 1874 and 1875National Library Foundation

In July 1874, also using the cable, French Havas, founded in 1835 in Paris by Charles-Louis Havas (1783–1858) and considered the world’s first news agency, began disseminating its content to Brazilian newspapers, in partnership with the British company later renamed Reuters. Havas-Reuters opened offices in Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Lima, and Montevideo. The partnership lasted until 1876, when the British agency left Latin America.

Havas carried on and maintained a monopoly over all international information in Brazil and Latin America for nearly half a century. “Brazil saw the world through French eyes, and the world saw Brazil through the very same eyes,” wrote Molina.

To cut costs, the agencies created abbreviations that allowed them to send telegrams with fewer words. “The notes were laconic and often published in full by the press, without editing or organizing the facts chronologically,” says historian Tania Regina de Luca, of São Paulo State University (UNESP), one of the organizers of the book História da imprensa no Brazil (History of the press in Brazil; Contexto, 2008).

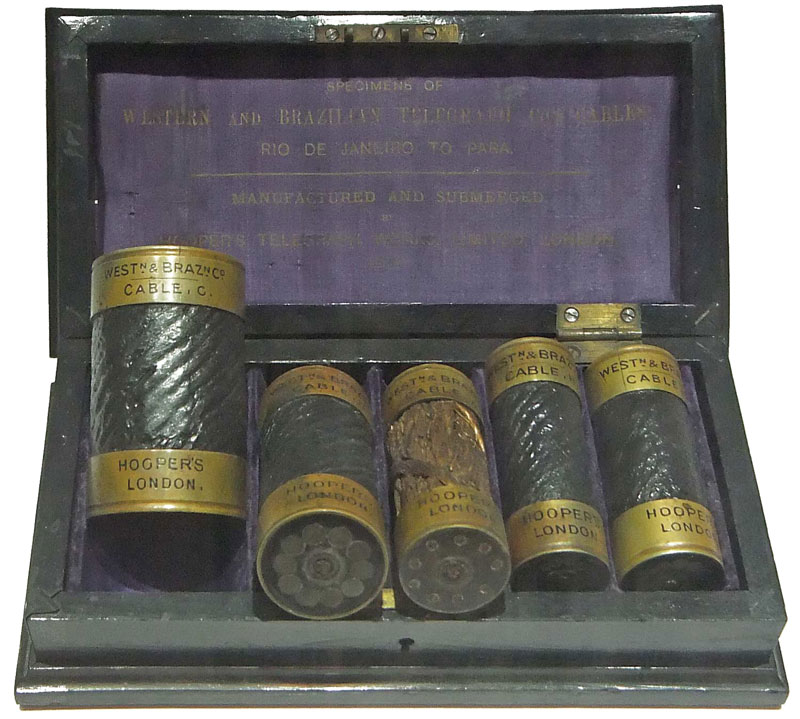

atlantic-cable.comCables from the Western and Brazilian Telegraph Company used in 1873 between Rio de Janeiro and Paráatlantic-cable.com

She encountered this dissonance in the news about the French politician Léon Gambetta (1838–1882), detailed in a chapter of the book Para uma história do jornalismo português no mundo (A history of Portuguese journalism around the world; Icnova, 2021). On January 2, 1883, the Rio de Janeiro newspaper Gazeta de Notícias announced his death, which occurred on December 31: “Telegrams. Gazeta de Notícias special service. Paris, January 1, at 11:50 a.m. Gambetta died. There is great sorrow throughout France. The funeral arrangements will be carried out by the state, it is said.

On January 11, 15, and 18, however, the Gazeta de Notícias published reports, which arrived by ship, from the Portuguese correspondent in Paris, Mariano de Pina (1860–1899), about the politician’s daily life between December 19 and 24, when he was still alive. It wasn’t until January 28 that the newspaper published an account by Pina of the circumstances surrounding Pina’s death. “The telegraph flashes, which often offered nothing more than fragmented data, written while the event was still taking place, had to be organized mentally by the reader himself,” says Luca.

Brazilian newspapers became better organized and reduced discrepancies between news stories at the beginning of the twentieth century. Other Brazilian agencies emerged, such as Agência Americana (1909–1930), created by writers and journalists, which only served the press and sent cultural and financial information abroad. In 1931, Paraíba businessman Assis Chateaubriand (1892–1968), owner of Diários Associados, created Meridional, to disseminate information for his communication network, which at its peak had more than 100 newspapers, magazines, and radio and TV stations.

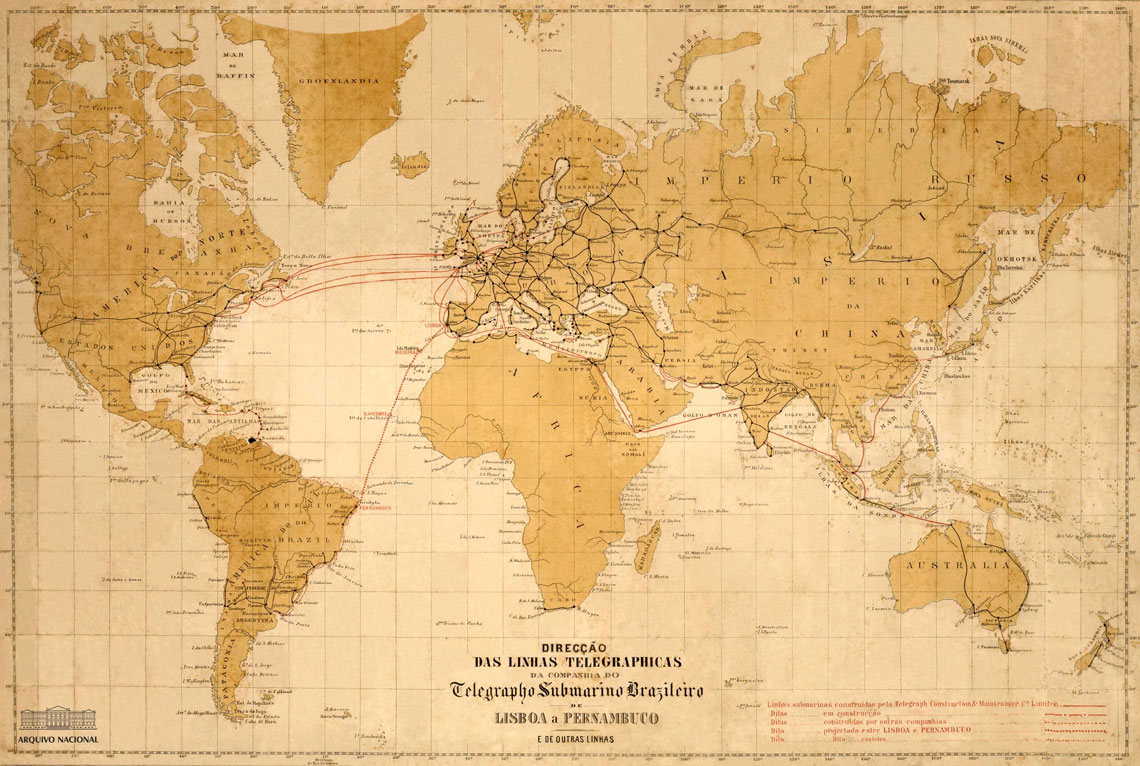

National ArchiveTelegraph lines in operation around the world in 1880National Archive

Over time, two devices replaced the telegraph: the teletype, which allowed operators to send and receive messages using a keyboard like that of a typewriter and a printed paper output; and the telex, used until the 1990s, which allowed a message to be sent to a specific recipient because each machine had an address, much like email.

In the late nineteenth century, the electrical pulses of Morse code, created by American inventor Samuel Morse (1791–1872), ran through submerged cables carried by copper conductors coated with gutta-percha latex (Palaquium sp.). “At the time, the material that provided the best electrical insulation and guaranteed the impermeability of the wire was gutta-percha, a natural polymer similar to rubber,” says physicist Mauro Costa da Silva, from Colégio Pedro II, who studied electrical telegraphy in Brazil from 1852 to 1914 as part of his doctorate, which he defended in 2008 at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

In the book The Victorian Internet, in which he shows how the telegraph revolutionized nineteenth-century communication, English journalist Tom Standage observes that, at the time, gutta-percha was as popular as plastic is today. Rigid at room temperature, it softens when immersed in hot water and can be easily molded. “Dolls, chess pieces, and ear trumpets were all made of gutta-percha. And although expensive, it turned out to be ideal for insulating cables,” he says in the book.

It was not easy to transmit electricity over long-distance submarine cables without the signals being distorted or the high voltage breaking them. After the first short cable was installed between France and England, under the English Channel, in 1851, it was thought that the same type of cable could be used for long distances. “With the longer cables, however, the short-lived signals arrived at the other end weak, making the message incomprehensible,” Silva explains. According to him, this problem occurred only in the submerged cables, but not in those installed in poles, indicating that the external environment—the salt water or the air—affects the transmission of pulses that carry the information.

National ArchiveTelegraph workers from the Empresa Brasileira de Correios e Telégrafos in 1934National Archive

The problems became even more evident when American investor Cyrus Field (1819–1892) decided to install a cable between the United Kingdom and North America, in 1858. Use of a very thin conductor and porous insulation led to interrupted message transmission after one month. Called upon to fix this issue, Irish physicist William Thomson (1824–1907), who would later be known as Lord Kelvin, found that the electrical conductivity of the copper samples taken from submarine cables, which he examined, varied greatly.

In 1866, introduction of the Ohm Law, according to which the intensity of the electrical current varies linearly, on a regular scale, according to the diameter of the wire, made it possible to install another cable, this time with high connectivity, between Europe and North America. The wire was thicker and had a lower voltage. “Creation of the Ohm Law was fundamental for ensuring the quality of submarine cables and for determining any insulation failures in the cable that had already been installed,” said Silva in an article from May 2023 in the Brazilian Journal of Development. From that point forward, submarine cables stretched between continents.

In the 1870s, the companies owned by Scottish merchant John Pender (1816–1896) commanded a worldwide network of submarine cables. Pender created the WBTC and the Brazilian Submarine Telegraph Company (BSTC), which would merge into the Western Telegraph Company (WTC), using the concession granted by businessman Irineu Evangelista de Sousa (1813–1889), then Baron of Mauá, who in 1872 had obtained the right to operate telegraph services between Brazil and Portugal.

Nan Palmero / Wikimedia CommonsRecent submarine cables on display in a museum in Prague, Czech RepublicNan Palmero / Wikimedia Commons

Coated with plastic or steel wires, fiber optic cables, the descendants of their telegraphic counterparts, began crossing the seas in the late 1980s, sometimes along similar routes. “The first submarine transatlantic telegraph cable that arrived in Brazil in 1874 ran along a similar route to the high-capacity fiber optic cable inaugurated in 2021, which connects Fortaleza to Portugal,” notes computer scientist Michael Stanton, a retired UFF professor and researcher at the Brazilian National Research and Education Network (RNP). The fiber optic cable was 3.9 miles long and lay at a depth of 13,000 feet, at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

According to Stanton, the maintenance required for submarine fiber optic cables is similar to that of the first telegraphic cables: for each, to be repaired when broken, they must be pulled from the seabed and mended on the surface of the ship before returning to the seabed. But the differences between them are great: “The Victorian technology used a single metal cable, protected from contact with water by gutta-percha and the signals were transmitted electrically and at low transmission rates,” he describes. “Today, a single cable uses several pairs of electrical circuits, protected from one another. The 2021 system includes four pairs of electrical cables, twisted together, simultaneously transmitting dozens of signals from different users.

Like telegraphic cables, which can be damaged by marine animals, fiber optic cables are also vulnerable. In January 2022, an underwater volcano erupted in the Tonga archipelago, east of Australia, breaking the only cable connected to Fiji, another South Pacific archipelago, leaving its population nearly incommunicado for around a month.

Responsible for more than 90% of global data transmission between the continents, 574 submarine cables connect all of the continents except Antarctica, according to US data company Telegeography. In Brazil, one of the network’s hubs is in the city of Fortaleza, from which 17 submarine fiber optic cables run to various areas of Brazil, South America, the United States, Europe, and Africa.

Scientific articles

AGUIAR, P. Antes do cabo: As agências de notícias na imprensa brasileira no período pré-telegráfico (1851–1874). Revista Brasileira de História da Mídia. Vol. 11, no. 1. Jan. 2022.

SILVA, M. C. O cabo telegráfico submarino e sua influência sobre a teoria eletromagnética. Brazilian Journal of Development. Vol. 9, no. 5. May 2023.

Books

MOLINA, M. M. História dos jornais no Brasil – Da era colonial à Regência (1500–1840). São Paulo: Cia das Letras, 2015.

MARTINS, A. L. & LUCA, T. R. de. (Eds.). História da imprensa no Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto, 2008.

LUCA, T. R. de. “Mariano de Pina na Gazeta de Notícias (1882–1886).” In PENA-RODRÍGUEZ, A. & HOHFELDT, A. Para uma história do jornalismo português no mundo. Lisbon: Livros Icnova, 2021.

STANDAGE, T. The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century’s online pioneers. New York: Berkley Books, 1998.