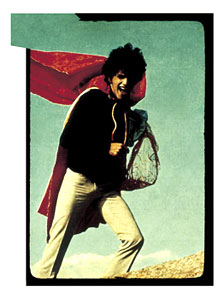

cosacnaifyCaetano Veloso wearing a Parangolé (a sort of cape that does not reveal its colors, forms, textures or the materials it is made from other than through the movements, the dance, of the wearer)cosacnaify

Music has been “tropicalist” for 40 years. During this time, the most significant trends in the music market followed the recipe for efficiency planted by “Tropicalism” or the “Tropicalia” musical movement led by Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Tom Zé, Torquato Neto, Mutantes and others: this recipe combines supposedly antagonistic or opposite elements to generate a third thing, hybrid and ethnically mixed, just like Brazil. Author of the book Tropicalismo – Decadência bonita do samba [Tropicalism – The attractive decadence of samba] (Boitempo, 2000), journalist Pedro Alexandre Sanches emphasizes that the discussion that fuels the Tropicalia movement is related to the combination of the old and the new, the traditional and the modern, men and women, right and left and many other dualities, with the objective of generating a third element, a new trend. “The impure category moves things, it is racial democracy applied to music and this is great because we aren’t pure in racial terms,” he points out.

The conclusion is that after so many years, Tropicalism has been incorporated into the national culture – and reiterated in this era of globalization in its broadest sense -, but is yet to be entirely digested. The concept exists. Total acceptance of it, however, does not. In the academic community, the topic has been studied for a number of years, but only recently has it begun to go beyond music – and some fine arts – to touch upon other segments, such as fashion, the media and behavior.

This dimension was efficiently achieved by the exhibition Tropicalia – Uma revolução na cultura brasileira (1967-1972) [Tropicalia – A revolution within Brazilian culture], which ended on September 30. The exhibition had originally been shown two years ago at Chicago’s Contemporary Art Museum. The event included a catalogue launched in Portuguese by Cosac Naify publishers. The exhibition, whose curator was Carlos Basualdo, was the only major event to celebrate the anniversary of the Tropicalia movement. Even so, in Brazil, it was shown only in Rio de Janeiro; São Paulo, where everything began, was left out.

This lack of interest is entirely out of proportion to the value of the movement. Although a reasonable bibliography has been published on the topic, a number of aspects are yet to be explored. Feliciano José Bezerra Filho’s 2005 doctoral thesis, Ressonâncias da Tropicália – Mídia e cultura na canção brasileira [Ressonances from Tropicália – Media and culture in Brazilian songs], presented at Unicamp, focused on the topic. Bezerra Filho points out the difficulty of referring to Tropicalia as a “movement,” and believes that its speed of historical intervention may be the cause of this difficulty. “We need to improve the debate on musical genres.”

The researcher questions whether Tropicalia created a musical genre and if it is possible to talk about music of this genre out of the historical context of 1967/68. “We know that it is possible for a composer to compose a bossa nova song intentionally nowadays, because the bossa nova genre is now fully established. But what about Tropicalia? Was it merely an attitude? In my opinion, these issues deserve to be explored in depth.”

Eduardo Larson’s master’s degree thesis, Tropicalismo: Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, o disco-manifesto Tropicália ou panis et circensis [Tropicalism: Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, the Tropicalia album-manifesto or panis et circensis], presented in 2006 at Unicamp, states that this topic has been studied quite often; however, there is a lack of truly consistent studies on related issues other than the historical and/or biographical ones. “The research possibilities are still wide open in relation to the musical language and the lyrics of the tropicalists, especially of those other than Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil.” To exemplify, he mentions the participation of Rogério Duprat in the tropicalists” albums and performances.

Two points related to Tropicalism ought to be explored in depth, says Maria Claudia Bonádio. First, the movement’s media potential, i.e., its presence in advertising, in the TV show Divino maravilhoso [Marvelous divine] and in the photographs and articles on the movement in the “mundane” press – the culture sections of newspapers and magazines. The second point is the visual make-up adopted by the movement. “The lyrics of the songs have been extensively analyzed, but I don’t know of any studies that study in-depth the visual appearance of the main proponents, such as Gil, Caetano, Gal and the Mutantes; the record album covers, etc.”

In his study, Bezerra Filho aimed at showing the influence of Tropicalia, the possibility of resonances in the subsequent work of other performers who, consciously or unconsciously, used the base launched by Tropicalia. “In my opinion, any investigation about the understanding of the movement must be based on the major tropicalist synthesis, which combines multiple interests and the merger of pop culture, the culture industry and the avant-garde,” he says. “It was a time when popular Brazilian music experimented with the possibility of a synthesis of these three elements, which is what made Tropicalia great.”

cosacnaifyThe play O rei da vela, directed by José Celso Martinez Corrêa, 1967cosacnaify

In this respect, he goes on, it has been proven that culture can never be viewed unilaterally, that the creative urges should always stay alive and look toward the future and that, at the same time, aspects of these same urges must be recognized in previous moments. “Free transit through musical genres and forms,” says the researcher, “was a tropicalist claim, fulfilled in an intelligent and transgressing manner within the Brazilian musical environment, which was normally compartmentalized and increasingly very segmented.”

Maria Cláudia, who teaches fashion, presented her doctoral thesis O fio sintético é um show!: moda, política e publicidade Rhodia S.A. – 1960-1970 [The synthetic fiber is the show!: Rhodia S.A. publicity, policies and fashion], in 2005 at Unicamp. In her thesis, Tropicalism is viewed from an original point of view. In 1955, she says, Rhodia obtained the patents for the production of synthetic threads and fibers in Brazil. To promote their use, between 1960 and 1970, the French company implemented an advertising policy. This task was coordinated by Lívio Rangan, the head of advertising, who chose to target the ads directly at the end consumer. This was the beginning of a regular production of catwalk shows, fashion editorials and fashion ads in Brazil. Various places (Pelourinho, the beaches in the Northeast, Brasília), performers (Nara Leão, Sérgio Mendes, Mutantes) and themes (coffee, exotic landscapes, soccer) were used to add Brazilian characteristics, life style and international quality to the Rhodia products and brands. Resorting to performers and aesthetic elements associated to Tropicalia in the fashion editorial (published in Jóia, a ladies” magazine, in April 1968) and the catwalk-fashion show Momento 68 had the same purpose.

Rhodia

This happened because one of the characteristics of Tropicalism was to blend national pop references with international pop. “I point out that, by resorting to Tropicalia as a theme, Rhodia’s advertisements did not intend to emphasize values that some of the critics and academic studies associated with the movement, such as criticism of the military regime and the culture industry. The intention was to present advertisements based on the recovery of popular and archaic aspects of Brazilian culture, filled with international aesthetic references.”

The researcher explains that in addition to the national/international, archaic/modern blend, Rhodia’s advertising, by resorting to Tropicalism, reinterpreted the “green and yellow spirit” [these being the two main colors of the Brazilian flag], as defined by Marilena Chaui, incorporating the aforementioned elements into a new national mythology, according to which being absurd was the new sign of the Brazilians” supreme originality. “It’s hard to measure the reach of the advertising campaigns and shows, but it seems to me that when the media absorbs or bets on a movement, it’s because this movement has already become successful; it has become a hit, it’s sellable.”

Maria Cláudia intuitively believes that associating Tropicalia with fashion helped strengthen the movement’s avant-garde nature. “I believe it is possible to transpose the opinions of Gilda de Mello e Souza on fashion creators to the creative work of advertising. Gilda de Mello e Souza defines a fashion creator as someone who has to be aware of the social moment and sense the aesthetic depletions that are about to take place. These are impressions rather than statements.”

Another aspect she believes important to highlight is that Rhodia’s advertising, by resorting to Tropicalia, did not appropriate the clothes worn by the main Tropicalia exponents, such as the crazy outfits of the Mutantes or the sloppy hippie style adopted by Caetano and Gil. “These editorials and fashion shows were entirely in line with international fashion and showed the main fashion trends, such as the straight-legged pant suits in the style of Courrèges, and the sexy dresses that mirror the fashion of the thirties, among others.”

Popular

Would Tropicalism have succeeded without the media” Bezerra Filho states that, as the press was able to follow the facts and musical manifestations, providing wide media coverage of the pop music festivals broadcast on TV, interest in the movement was natural, because of the thirst for novelties that fuels the media system as a whole. However, he adds that historical importance resulted from the innovative aspect itself rather than from some deliberate media strategy. “The cultural debates at the time were heated and the tropicalists joined the discussions about Brazilian pop music and culture, with unique levels of reflection, arousing the interest of sectors involved in Brazil’s music culture.”

Sanches points out that the media played an important role in Tropicalia regarding two different moments. Initially, the movement divided opinions and was even denigrated by the purists, while a segment of the press viewed the proposal as modern and avant-garde. From the eighties onwards, however, the movement became hegemonic, almost a unanimity, thanks to a strong discourse, but with undeniable antecedents such as bossa nova, which was innovative because it mixed samba and jazz. Caetano’s tendency to argue with the press strengthened this notion. “Tropicalism still thrives on controversy and on battles, but deep down there is mutual admiration between the two parties.”

The historical importance of Tropicalism is mainly associated with the artistic production of “these people who were highly intelligent and creative, and also with their position regarding the political and behavioral tendencies at that time.” This does not mean that the performers were naive in relation to the avant-garde. “On the contrary – but there was no avant-garde program to be followed.”

Republish