After being admitted to Lisbon Hospital for syphilis treatment, Luís Vaz de Camões wrote to a friend around 1550. “In a jocular tone, and referencing Greco-Roman mythology, he talked about the place and the diseases of sexual desire aroused by the arrows of Cupid,” recounts Marcia Arruda Franco, a Portuguese literature professor at the University of São Paulo (USP). The missive, theretofore unpublished, is grouped in with another five letters attributed to the Portuguese poet in the book Cartas em prosa e descrição do Hospital de Cupido (Letters in prose and depiction of the Cupid Hospital) (Madamu, 2024), arranged by Franco. “Camões flitted between taverns and brothels, and in these texts he demonstrates the vices and other ‘sins’ of the sixteenth-century literary period,” adds the researcher, who collated the material at the National Library of Portugal.

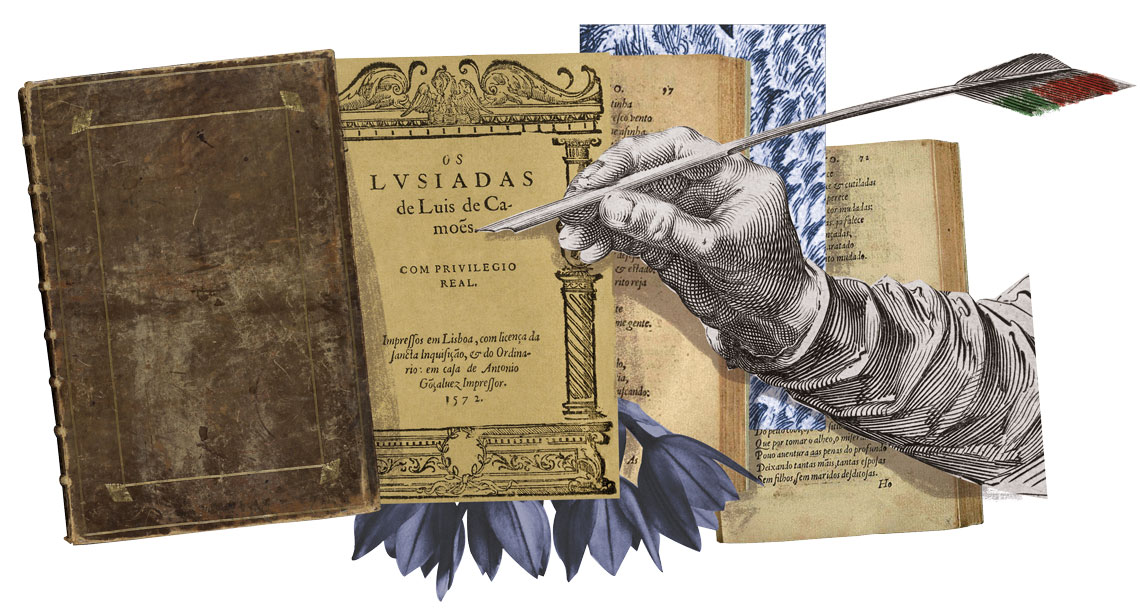

The launch took place on Camões’s 500-year birth anniversary; he is lauded as one of the greatest ever Portuguese-language poets, and author of Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) (1572), an epopee (epic poem) of 8,816 verses narrating the sea voyage from Portugal to India between 1497 and 1499, led by navigator Vasco da Gama (1469–1524). This historic event has given rise to a series of tributes to the celebrated literatus. In Brazil, for example, the Royal Portuguese Reading Room in Rio de Janeiro is staging the event Quinhentos Camões: O Poeta Reverberado (Camões Five Hundred: The Celebrated Poet) until June 2025, with a monthly roundtable featuring guests from Brazil and overseas. Until October this year, the National Library hosted the in-person exhibition A língua que se escreve sobre o mar – Camões 500 anos (Language written on the sea – Camões 500 years), whose 38 pieces can also be viewed virtually, including early-edition covers of The Lusiads and literary works inspired by all things Camonian, including cordel literature (short story and poetry pamphlets that traditionally hung from strings in the street).

The commemorations in Portugal are set to continue until 2026, having officially commenced on June 10 at the University of Coimbra. This is widely considered to be the date of Camões’s death in 1580—the poet’s precise date of birth is unknown. “This is one of the many gray areas in the history of Camões,” says Portuguese writer Isabel Rio Novo, author of the recently released Fortuna, caso, tempo e sorte: Biografia de Luís Vaz de Camões (Fortune, fate, time, and luck: The biography of Luís Vaz de Camões) (Contraponto, 2024), as yet unpublished in Brazil. “It is known that he was born between 1524 and 1525: according to a document from 1550, the poet was then 25 years old.”

The author, a PhD in comparative literature from the University of Porto, wrote the book over five years. One of the challenges was navigating through all the rumors and myths involving Camões’s life journey. USP’s Franco based a similar challenge on editing the book Vidas de Camões no Século XVII (Lives of Camões in the seventeenth century) (Madamu, 2024). The Brazilian researcher, a member of the University of Coimbra’s Interuniversity Center for Camonian Studies, collated four of the so-called “life accounts” by Camões, and an epitome, all from the seventeenth century, signed by authors such as Manuel de Faria e Sousa (1590–1649). “These are printed texts, together with editions of Camões’s works, aimed at conjuring a mythical image of the poet, but they are full of gaps and appear to speak of different people, given the number of contradictions between them,” she says.

Isabel Rio Novo points out another challenge: the scarcity of sources. As well as Portugal, she has gathered information in other countries, both virtually, from the Brazilian National Library website for example, and in person, from archives in India and Mozambique. She discovered previously unknown sources during her research, such as a document on the incident that saw the poet incarcerated in 1552. “He insulted Gonçalo Borges, a servant of the Royal House, during a religious festival in Lisbon, and was sent to the Tronco Prison. Camões was arrested on a number of occasions, mostly for fighting,” says Rio Novo.

The writer was freed the following year after the then Portuguese monarch João III (1502–1557) issued a letter of pardon to Camões, in exchange for which he served as a soldier in the Lusitanian Army on an expedition to India, arriving in Goa in 1554. According to the biography, this was not his first military experience. In 1549, while participating in a Portuguese mission to North Africa, he lost an eye. “Camões fell victim to a firearms accident, probably a cannon fired by a fellow soldier, with a spark striking his eyeball,” the researcher goes on.

The poet served the Portuguese Empire for seventeen years. “Camões was of noble origins, but his family lost its wealth over the generations. Although well connected, he was a man of few means who had to work to survive,” she says. Among other functions, in 1562 he became Chief Administrator of the Dead and Absent, dealing with the estates of those who had not nominated proxies in their wills. He took on this role in Macau, then a Portuguese trading hub, now part of China.

After being removed from this post and surviving a shipwreck in the Mekong River Delta in Southeast Asia, in 1567 Camões set sail for Mozambique, where he lived under precarious conditions. Helped by friends, he returned to Portugal three years later and finished The Lusiads in his native land, and the work was published in 1572. That same year, the poet was granted a modest pension, paid irregularly, which continued until the end of his life. According to the biography, this was primarily a reward for Camões’s seventeen years in service of the Portuguese Empire, but the process was fast-tracked as the epic poem had been dedicated to reigning King Sebastião I (1554–1578).

“Camões is one of the greatest poets ever, first and foremost for the way his poetry epitomizes an aristocratic experience, elements of Christian philosophy formulated primarily by St. Augustine [354–430] and St. Thomas of Aquinas [?–1274]; the Greco-Roman culture based on the writings of Plato [c. 428–347 b.c.] and Cicero [106–43 b.c.], among others. He was also greatly influenced by Italian poet Francesco Petrarca [1304–1374],” says João Adolfo Hansen, emeritus professor at the USP School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH). “All these elements can be found in The Lusiads.”

Divided into ten cantos, the epopee is considered to be his masterpiece. “Perhaps it is the first modern Portuguese-language poem, as, among other aspects, it is open to contradiction, to ambiguity; it does not answer, but rather asks,” says Luis Maffei, Portuguese literature professor at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), set this year to release a new edition of the work in partnership with Paulo Braz, of the Vernacular Letters Department at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). “We have attempted to reproduce the rhythm of the first edition, which has been altered over the years, primarily during the twentieth century, and to correct inaccurate interventions by past editors, such as changed words and punctuation,” explains Maffei, who since 2012 has promoted the annual event “A day with Camões” at UFF. With this anniversary of the poet’s birth, the gathering will be held monthly until mid-2025.

Veridiana Scarpelli

Veridiana Scarpelli

By associating history with literature, other language versions of the epopee have been produced. The first translation into English was released in 1655. “Camões was read in places such as England and Germany, influencing the advent of Romanticism in these two countries from the end of the eighteenth century,” says Matheus de Brito of Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), who undertook a postdoctoral internship on Camões—supported by FAPESP—at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP).

The variety of translations is one of the topics addressed by the dossier “Além da Taprobana…memórias gloriosas: Os Lusíadas 450 anos” (Beyond Taprobana…glorious memories: 450 years of The Lusiads), released by USP’s journal Desassossego last year. “In Russia, for example, there was an indirect translation from the French language at the end of the nineteenth century, after another incomplete one in the 1940s, and finally a version by scholar Olga Ovtcharenko in 1988. In Japan, there is a total of three translations available, the first published in 1972,” explains Mauricio Massahiro Nishihata, professor at the Federal Institute of Rondônia (IFRO) and one of the organizers of the dossier under the supervision of Adma Muhana, Portuguese literature professor at USP.

In search of a hero

On the other hand, the juxtaposition between history and literature has caused The Lusiads to be confused with the identity of the Portuguese nation. “In 1580, Portugal lost its political independence and found itself under the yoke of Spain for 60 years. This was significantly traumatic for the Portuguese, and Camões came to be used as a symbol of that glorious past,” says Sheila Hue, of UERJ, who is also preparing a critical edition of The Lusiads, with Simon Park, of the UK’s University of Oxford. “The work very quickly became a canon, and this great Camonian image practically overshadowed other contemporary Portuguese poets.”

Appropriation of the Camões personality has pervaded through the centuries. “When King João VI [1767–1826] transferred his Court to Brazil in 1808 to escape from Napoleon [1769–1821], Portugal was somewhat leaderless and facing financial difficulties. In the search for a hero, Portuguese Romanticism unmasked the image of a subversive, revolutionary Camões,” comments Sabrina Sedlmayer, professor of Portuguese literature at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). The twentieth century saw the Salazar dictatorship (1933–1974) make use of the strategem. “To spread civil-mindedness, patriotism, and honor, the New Portuguese State returned to the heroic, glorious past of the conquerors. Camões was thus elected as an icon of nationalist propaganda,” adds the researcher, current president of the International Association of Lusitanists (AIL).

The Lusiads is one of the few works whose authorship can be credited to Camões. “During his life, he published three other poems, and much of his lyrical poetry was only published in the book Rhythmas, released 15 years after his passing, because until then only epic or religious poetry was published in Portugal,” recounts Hue, a member of the Interuniversity Center for Camonian Studies at the University of Coimbra. A second edition of the epic work was released in 1598, with other poems added, such as the celebrated Amor é fogo que arde sem se ver (Love is a Fire that Burns Unseen), and two letters. According to the researcher, at that time the book’s editor asked people to send in poems penned by Camões. “But nothing was autographed, nothing was signed by the poet,” explains Hue. “There were also manuscript poems in what were then called songbooks, hand-copied pieces from the sixteenth century. Many of these are attributed to Camões.”

Alongside the letters and sonnets, Camões wrote the theater pieces Auto de Filodemo (Play of Filodemo) and Auto dos anfitriões (Play of the hosts), both from 1587, in addition to Auto d’el-rei Seleuco (Play of King Seleuco), whose creation is attributed to the poet, and was staged in 1645. “The Camonian corpus has, since the sixteenth century, been somewhat like an accordion, expanding and retracting according to predominant philological criteria,” says Alcir Pécora, of UNICAMP. “I am much more interested in the reading of the poem than trying to find out its real authorship. For those that study works from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, that is almost impossible. In those days, poetry was vocalized, with poems copied by hand, and those doing the copying often felt empowered to ‘improve’ the poem. In other words, in practice I think of Camões more as the name of a corpus than a specific man.”

Some scholars have attempted to organize Camonian output. In a 1980 edition, author Cleonice Berardinelli (1916–2023), a professor at UFRJ, collated 400 poems attributed to Camões on one occasion or another. “She did not attempt to define what Camões really wrote, as she knew that this was impossible,” says Hue. “On bringing the works together, she shone a light on the nature of the poetry of that time, based on imitation, oral circulation, and manuscript, which generated multiple versions and different authorships.” Between 1985 and 2001, Leodegário de Azevedo Filho (1927–2011), a UERJ philologist and professor from the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco, published Lírica de Camões (Camões lyrical), a seven-volume series bankrolled by the Portuguese State publishing house Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda. In this work, he defines that the minimum Camões corpus has 133 sonnets, based on what he called the “dual testimony of the manuscripts.” In other words, each of the collated texts is said to have two evidential proofs from the sixteenth century.

Camões came to know a large part of the Portuguese empire, but never visited Brazil. “In any event, people began reading his work here during the colonial period, and we can see his influence in epics such as Prosopopeia [1601], by Bento Teixeira [c. 1561–1618], and À ilha de maré [To the island of the tide] [1705], by Manuel Botelho de Oliveira [1636–1711],” says Marco Lucchesi, UFRJ professor and current president of the National Library Foundation. “In the nineteenth century his presence was already consolidated in Brazil, and since then several authors have paid homage to the poet, including none other than Machado de Assis [1839–1908], Jorge de Lima [1893–1953], and Manuel Bandeira [1886–1968].” For Sedlmayer, of UFMG, this influence has continued to the present day in verses by creators such as Caetano Veloso and Gregório Duvivier. “Camões’s staying power seems endless,” she concludes.

The story above was published with the title “The poet’s lasting voice” in issue 345 of November/2024.

Project

The ethos of dissent in the poetry of Luís de Camões (nº 17/11260-4); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Antonio Alcir Bernardez Pécora (UNICAMP); Beneficiary Matheus Barbosa Morais de Brito; Investment R$319,400.46.

Scientific article

HANSEN, J. A. Máquina do mundo. Teresa. Vol. 1, no. 19, pp. 295–314. Dec. 2023.

Books

CAMÕES, L. V. de. 20 sonetos. Introdução e edição comentada de Sheila Hue. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp, 2018.

CAMÕES, L. V. de. Cartas em prosa e descrição do Hospital de Cupido. Introdução, notas e proposta de fixação textual Marcia Arruda Franco. São Paulo: Madamu, 2024.

MARIS, P. de et al. Vidas de Camões no século XVII. Edição, introdução, tradução e notas de Marcia Arruda Franco. São Paulo: Madamu, 2024.

RIO NOVO, I. Fortuna, caso, tempo e sorte: Biografia de Luís Vaz de Camões. Lisboa: Contraponto, 2024.

Dossier

NISHIHATA, M. M. et al. (Eds.). Além da Taprobana… Memórias gloriosas: Os Lusíadas 450 anos. Desassossego, USP, Vol. 15, no. 29. 2023.