IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F01-001 Archives

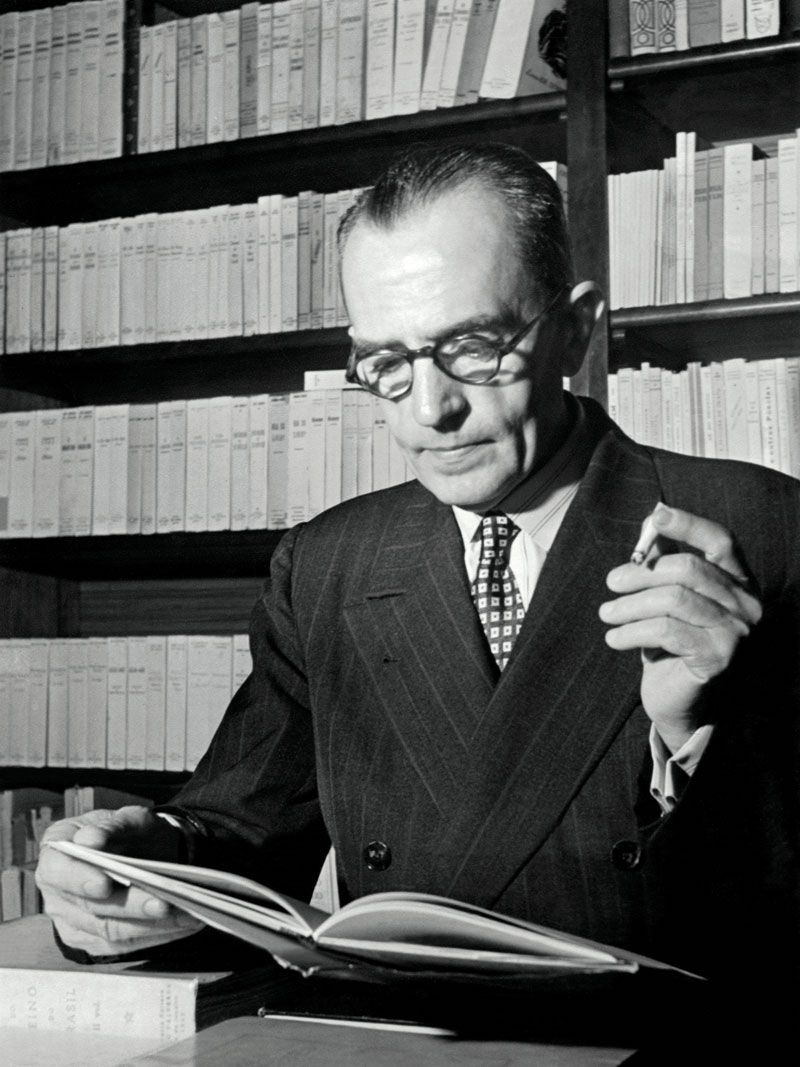

Ramos at the José Olympio bookstore in Rio de Janeiro, 1942IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F01-001 ArchivesIn the early years of the 1930s, the Brazilian literary scene was marked by the publication of works of fiction that sought to denounce the precarious reality of sertão (badlands) workers and laborers in northern and northeastern Brazil. Released at a time when this genre of socially minded regionalist novel was experiencing its decline, giving way to fiction of a more intimate and psychological nature, Graciliano Ramos’s (1892–1953) Vidas Secas broke ground by centering its narrative upon subjective aspects of a family of retirantes (migrants from the North and Northeast of Brazil that travel south in search of a better life), without focusing on constructing a thorough portrait of Brazilian society in these regions, as did other writers of the period.

Ramos’s book tells the story of Fabiano and his family, made up of his wife Sinhá Vitória, his two sons, and Baleia the dog, who roam the arid landscape of the Northeast until they find shelter in an abandoned farmhouse. During the rainy season, when the landowner returns, Fabiano starts working as a cowboy on the farm, where he settles permanently. In a letter sent to a journalist and reproduced in O velho Graça – Uma biografia de Graciliano Ramos (Old Graça: A biography of Graciliano Ramos; Boitempo Editorial, 2012)—written by Dênis de Moraes, professor at the Department of Cultural Studies and Media at Fluminense Federal University (UFF)—Ramos explained that his intention was to expose “the soul of the rugged and almost primitive being who lives in the most remote area of the sertão, to observe the reaction of this rough spirit before the outside world, that is, the hostility of the physical environment and human injustice”.

“Unlike authors such as Rachel de Queiroz [1910–2003], who in her novels presented different economic and social strata of the sertão society, including both exploited figures and their tormentors, closer in spirit to more traditional realism, Ramos focused his narrative on the story of the retirante family, creating a sense of isolation unprecedented in the fiction of that time,” analyzes critic Felipe Bier Nogueira, who is developing postdoctoral research on the subject at the Institute of Language Studies, at the University of Campinas (IEL-UNICAMP).

Brasiliana Guita and José Mindlin Library – PRCEU / USP

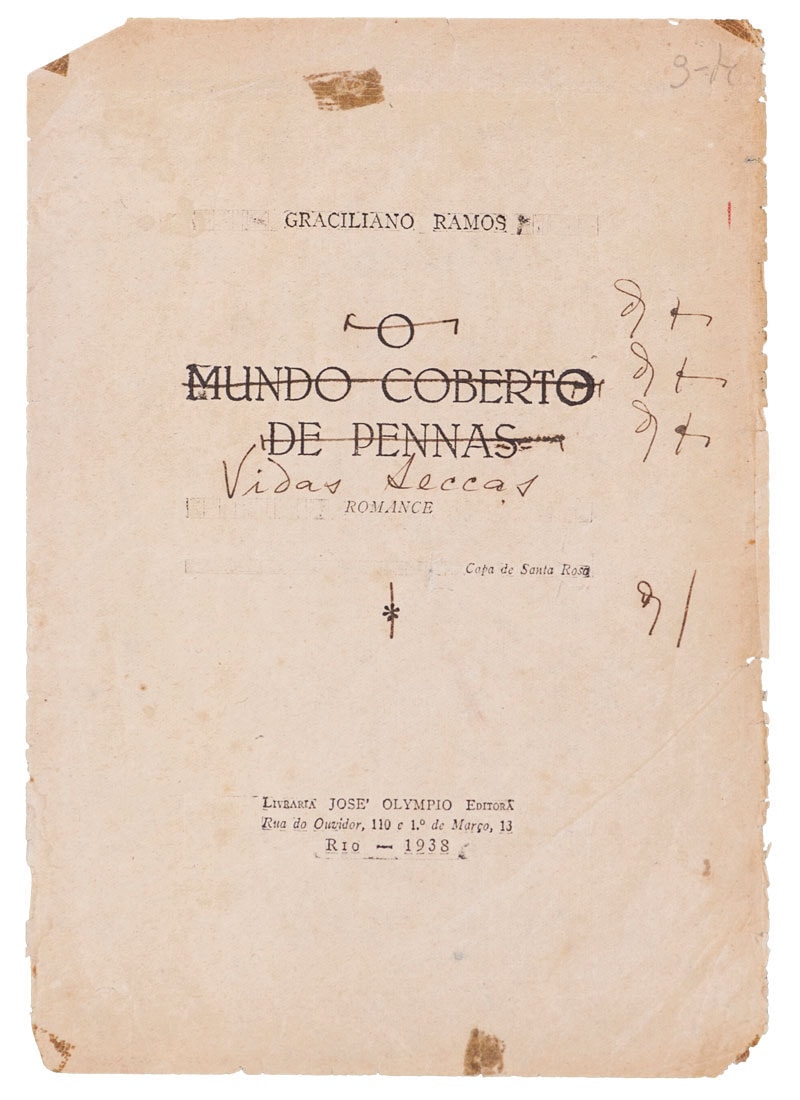

The author changed the novel’s title after seeing print proofsBrasiliana Guita and José Mindlin Library – PRCEU / USPAnother unique feature of the 1938 novel in relation to its contemporaneous works is the trajectory of the protagonists. While authors such as Jorge Amado (1912–2001) wrote stories that often featured marginalized figures who became revolutionary heroes, in Vidas Secas, Fabiano does not develop class consciousness, even after a lifetime of hardship and being exploited by his employers. “The novel is an attempt to show Brazilian reality without making concessions to the literary populism typical of other regionalist writers,” says Alfredo Cesar Barbosa de Melo, from the Department of Literary Theory at UNICAMP. According to Barbosa de Melo, this can be seen, for example, when Fabiano reencounters the soldier responsible for his improper imprisonment in the Caatinga (semi-arid scrublands). In this situation, he has the opportunity to take revenge, but restrains himself in deference to the position of authority held by the soldier.

Being Ramos’s only novel written in third person, in free indirect speech—a feature that at certain points makes indistinguishable to the reader the thoughts of the narrator and the characters—Vidas Secas relates to the author’s experience as a political prisoner for 10 months, between 1936 and 1937, first in Maceió and later in Rio de Janeiro, during the regime of Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954). According to Fabio Cesar Alves, professor of Brazilian literature from the Department of Classical and Vernacular Letters at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo (DLCV-FFLCH-USP), the “degrading” experience led the author to include the “other” in his fiction, hitherto focused on characters closer to his own social class, such as the public servant who appears in 1936’s Angústia (Anguish). The researcher claims that, by shedding light on the social hardship produced by the advance of capitalism, Vidas Secas also represents an attempt to demystify the ideology of progress. “The novel has a unique, concise aesthetic that concentrates problems in literary scenes,” he says.

3 IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-M-01.01 Archives

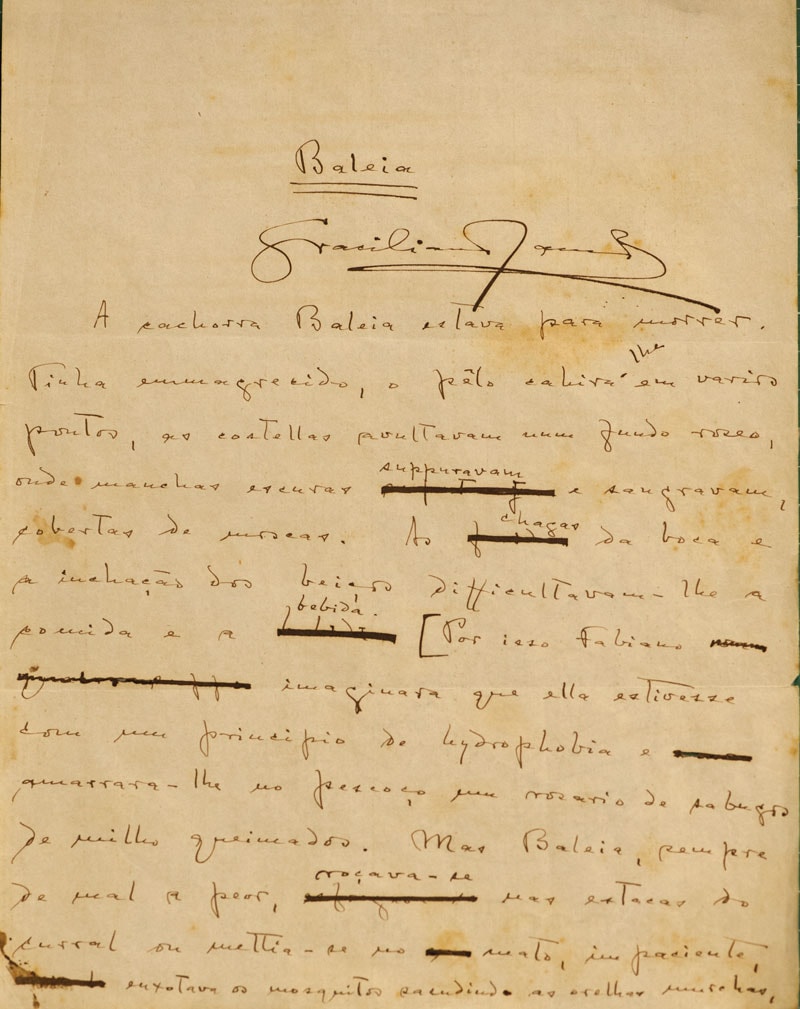

The manuscript of the first chapter, “Baleia”3 IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-M-01.01 ArchivesWritten in a boarding house

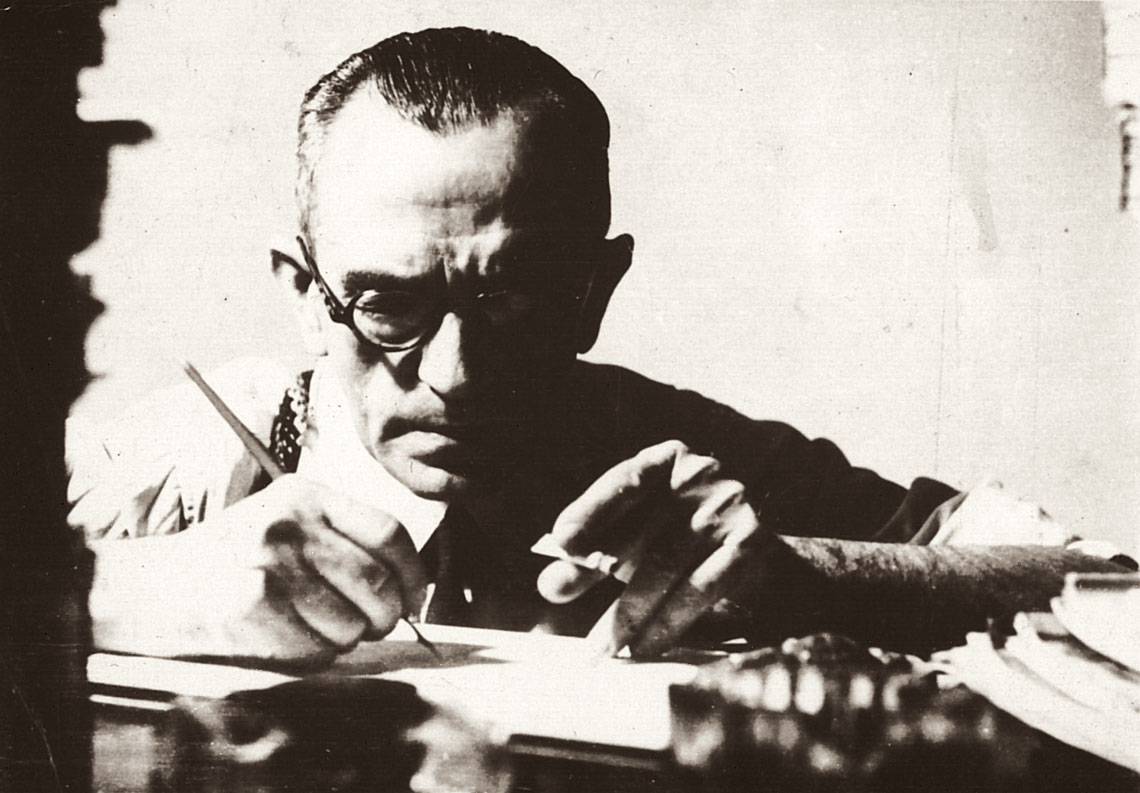

By the time Ramos published Vidas Secas, he was already an intellectually established writer, with three published novels: Caetés (Kaeté) (1933), São Bernardo (Saint Bernard) (1934), and Angústia. However, despite the recognition, he lived in a precarious financial situation, sharing a small room at a boarding house with his wife and two daughters—as pointed out by Thiago Mio Salla, a professor at the School of Communications and Arts (ECA) and at the FFLCH. In order to be able to write, Ramos took advantage of the early hours of the morning, while the children slept and the house was still quiet. He continued to write until dawn, “amid many cigarettes and a few sips of cachaça,” states the biography by Moraes. The novel’s chapters were written as short stories and published in different newspapers, such as O Cruzeiro, O Jornal, Diário de Notícias, and Lanterna Verde, from Rio de Janeiro, and also Folha da Manhã, from São Paulo.

Based on the author’s childhood experience in the Pernambuco sertão, where he witnessed a dog being put down, “Baleia,” the ninth chapter, was the first to be published in the literary supplement of O Jornal. The short story’s positive reception, especially among Ramos’s peers, motivated him to continue the story, whose initial title would be the same as that of the last chapter, O mundo coberto de penas (The world covered in feathers). After the printing of the first proofs, however, Ramos changed his mind and decided to name the novel Vidas Secas. The book was published by José Olympio and attracted the attention of critics, such as Otto Maria Carpeaux (1900–1978) and philologist Aurélio Buarque de Holanda (1910–1989), who celebrated its release.

IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F06-011 Archives

Actor Genivaldo Lima in Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s movie (1963)IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F06-011 ArchivesNevertheless, its success among intellectuals did not immediately translate into sales. Salla, of USP, recalls that, despite the commercial acumen of bookseller José Olympio, known for publishing authors of various ideological and political affiliations, the first 20,000 copies of Vidas Secas took a decade to sell. “In part, the novel took a long time to sell due to the public’s saturation with stories about the Northeast, but also because of the dryness of the narrative, which goes beyond portraying the reality of a family of retirantes,” says Bier of UNICAMP.

Over the years, the fact that parts of the novel were published at different times has generated debate among critics, who are interested in understanding to what extent this could have undermined narrative cohesion. Rubem Braga (1913–1990) classified it as a “detachable novel,” an idea later challenged by intellectuals, such as Antonio Candido (1918–2017), considered even by Ramos as the best critic of his literary career. “Despite its serial publication, the chapters cannot be read in any order. For example, the section where Fabiano reencounters

the soldier in the Caatinga cannot be read before the one in which he is unjustly arrested,” says Alves of FFLCH-USP.

IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR- F07-023 Archives

Heloísa Ramos in Brasília during a celebration for the 50th anniversary of the novel’s publicationIEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR- F07-023 ArchivesBrazilian imaginary repertory

In 1963, filmmaker Nelson Pereira dos Santos (1928–2018) adapted Vidas Secas for the screen. In 1972, Leon Hirszman (1937–1987) filmed São Bernardo, and in 1984 Santos shot Memórias do Cárcere (Memories from prison), published in 1953. Thanks to its “disembodied language,” which seeks to show the perverse effects of the advance of capitalism in a peripheral country like Brazil, Alves considers that Ramos’s work was well adapted by representatives of the Cinema Novo (New Cinema) movement, such as Santos and Hirszman. “The ideas of Ramos and Cinema Novo converge both in terms of socially conscious themes and their raw aesthetics,” he states.

Bier, of UNICAMP, believes that works, such as 1956’s Grande Sertão: Veredas (The Devil to Pay in the Backlands), written by Guimarães Rosa (1908–1967) could only be created because Ramos’s novel paved their way. “The formal procedure of Vidas Secas enabled other writers to work with rudimentary language in their literary works,” says the researcher. In the same vein, Melo Grande explains that the brevity of vocabulary used to depict the sertão in the novel allowed for the establishment of poetic parameters that were later recaptured by Guimarães Rosa, but taken in the opposite direction. “Grande Sertão: Veredas features an overflowing verbosity,” he ponders.

IEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F01-027 Archives

The novel was written during the early hours, while the family slept and the boarding house was quietIEB / USP / Graciliano Ramos Fund / GR-F01-027 ArchivesAfter Graciliano Ramos’s death, the rights to publish his work were sold to Martins Fontes and have belonged to Record since 1975. Translated into 17 languages, Vidas Secas is today the best-selling book in the publisher’s catalog, with just over 1.8 million copies sold and 138 editions. “As a novel emblematic of the 1930s, it served as an essential piece in the construction of Brazil’s imaginary repertory about the Northeast,” says Salla.

For Alves, “by attacking the pillars of bourgeois society, the novel goes beyond denouncing northeastern hardship.” In Salla’s assessment, the novel still offers new fields of research despite its established status. “Something that hasn’t yet been done is the critical analysis of the first edition manuscripts compared with subsequent editions, in order to examine the changes made to the work over time,” concludes the researcher.

Project

The malaise in tradition: Vidas Secas and the metamorphoses of the sertão (nº 16/21431-8); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Grant; Principal Investigator Alfredo Barbosa de Melo (UNICAMP); Scholarship Beneficiary Felipe Bier Nogueira; Investment R$493,262.20.