At the end of last year, the journal Chemistry World, published by the Royal Society of Chemistry, in the UK, decided to stop publishing an online ranking that was popular with readers. It was the list—updated a few times a year—of more than 500 highly productive researchers in the field of chemistry, those whose h-index was greater than 55. The decision to suspend the ranking was a capitulation to criticism that it placed too much emphasis on a single performance indicator, without taking into account other aspects of scientific production, and could induce universities and funding agencies make simplistic or questionable decisions. The h-index of a researcher is defined as the greatest number “h” of his or her research articles that have at least the same number “h” of citations. Chemistry World‘s highest ranked author was George Whitesides of Harvard University, with an h-index of 169. This is equivalent to saying that he published at least 169 articles that obtained at least 169 citations, each, in other papers. To have a high h-index, you must publish articles that create an impact in the scientific community. If a researcher publishes a lot, but is little quoted, or if she receives many citations, but publishes a limited number of articles, she will have a low h-index.

At the end of last year, the journal Chemistry World, published by the Royal Society of Chemistry, in the UK, decided to stop publishing an online ranking that was popular with readers. It was the list—updated a few times a year—of more than 500 highly productive researchers in the field of chemistry, those whose h-index was greater than 55. The decision to suspend the ranking was a capitulation to criticism that it placed too much emphasis on a single performance indicator, without taking into account other aspects of scientific production, and could induce universities and funding agencies make simplistic or questionable decisions. The h-index of a researcher is defined as the greatest number “h” of his or her research articles that have at least the same number “h” of citations. Chemistry World‘s highest ranked author was George Whitesides of Harvard University, with an h-index of 169. This is equivalent to saying that he published at least 169 articles that obtained at least 169 citations, each, in other papers. To have a high h-index, you must publish articles that create an impact in the scientific community. If a researcher publishes a lot, but is little quoted, or if she receives many citations, but publishes a limited number of articles, she will have a low h-index.

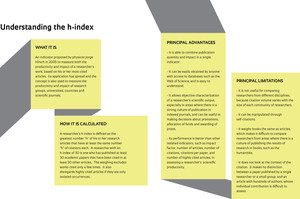

The h-index was proposed in 2005 by Argentinean physicist Jorge Hirsch, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, as a tool capable of taking into account both the quantity and quality of academic publications. It soon became a parameter used in assessments and on the business cards of researchers with outstanding performance, and is now being applied to measure the performance of groups of researchers, universities, countries and journals. According to Henry Schaefer, professor at the University of Georgia, Athens, and the person responsible for compiling the Chemistry World list, the criticism began with the first edition of the rankings in 2007 and never stopped. “The problem was not with the h-index itself, but with the ranking that placed too much emphasis on this indicator,” he explained.

Chemistry World’s experience reveals the benefits and drawbacks of the h-index, a measurement that has gained widespread application due to its merits—it is easy to calculate, it is based on objective criteria, and it summarizes in a single number the productivity and relevance of a researcher’s work. At the same time, it has become the target of criticism because it is used without taking its limitations into account. Jorge Hirsch himself admits that there is a significant problem. “One must always keep in mind that non-mainstream research may be little cited and underrepresented in bibliometric indicators, but it still deserves financial support,” he affirmed in the online magazine Research Trends. “A bibliometric indicator should always be used alongside other indicators, together with common sense.”

The h-index cannot be used to compare researchers at different stages in their careers—a senior researcher with an h-index of 100 in chemistry can be proud of her extreme productivity, but so can a young researcher in the same area with an h-index of 30. It is also misleading to compare the performance of researchers from different areas. “Each area has a unique size and different citation trends,” explains Rogério Meneghini, scientific coordinator of the SciELO Brazil library. “In biochemistry, for example, the number of researchers is huge. Therefore, there are more articles and more people citing articles. The rule is to look at sub-areas when making comparisons,” says Meneghini, who considers the h-index to be a valuable tool, especially in the natural sciences. “A high h-index in these areas is a sign that the researcher did important research,” he says.

The h-index cannot be used to compare researchers at different stages in their careers—a senior researcher with an h-index of 100 in chemistry can be proud of her extreme productivity, but so can a young researcher in the same area with an h-index of 30. It is also misleading to compare the performance of researchers from different areas. “Each area has a unique size and different citation trends,” explains Rogério Meneghini, scientific coordinator of the SciELO Brazil library. “In biochemistry, for example, the number of researchers is huge. Therefore, there are more articles and more people citing articles. The rule is to look at sub-areas when making comparisons,” says Meneghini, who considers the h-index to be a valuable tool, especially in the natural sciences. “A high h-index in these areas is a sign that the researcher did important research,” he says.

On the contrary, in many disciplines in the humanities, publication of research results in books is as important as publishing articles in indexed journals, in which case the h-index often says little about the actual impact of a researcher’s work. “In the humanities, a numerical impact index is certainly something to take into account, but only as one of several elements of assessment. Without taking into account qualitative features, it will be just a number,” says Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos, FAPESP assistant coordinator for Humanities and Social Sciences. “In addition, the impact of a publication is not measured by citations alone, but also by many other things such as contributions to technological innovations or the formulation of public policy, for example.”

The Italian Mauro Degli Esposti, a professor at the University of Manchester, recently compiled a list of researchers in all areas with an h-index over 100, based on data from Google Scholar. In his ranking, which includes almost 200 names, very few researchers in the humanities and applied social sciences appear, with exceptions like the Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz (h-index of 130) and the linguist Noam Chomsky (123). Senior scientists in medicine and biochemistry are overrepresented (see figure). There is no direct correlation between Nobel laureates and the top of the list. Among the top 30, only four have won the Nobel Prize and only one won the Fields Medal, the principal award for young mathematicians. “The only virtue I see in the h-index is the fact that it is easy to calculate,” says George Matsas, professor at the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp). “There is no clear criterion as to what constitutes a high or low h-index. I bet that the h-index of Peter Higgs, of the Higgs boson, or that of Kenneth Wilson, winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics, are lower than those of several other researchers who are less well-known,” he says.

Rogério Meneghini warns of an important distortion in the h-index: researcher participation in networks of up to 700 researchers in particle physics, astronomy or new drugs. “It would be a drastic step, but it might make sense to not include this type of article when calculating the h-index. Their results are important, but it is not possible to measure the real contribution of each author,” he says. “I have nothing against participation in international collaboration networks,” says Meneghini. “We have many Brazilian researchers continuously participating in networks of 20 or 30 scientists from various countries, and maintaining strong relationships with people from MIT, or from England or France. This is a sign of quality,” he notes.

FAPESP reviewers and members of Area Panels Committees use researcher h-indices as an auxiliary parameter in assessing the quality of a body of articles, but FAPESP also continues to depend on the extensive opinions of peer reviewers and qualitative analysis to select the best proposals. “The most important aspect, in our view, is the quality of the research proposal,” says Wagner Caradori do Amaral, professor in the University of Campinas (Unicamp) Electrical and Computer Engineering (FEEC) Department, and assistant coordinator of the FAPESP Scientific Board in the area of Sciences and Engineering. “If the proposal is of good quality and the proposer demonstrates the potential to accomplish it, the h-index will not prevent the researcher from receiving funding,” says assistant coordinator José Roberto Postali Parra, professor at the University of São Paulo Luiz de Queiroz School of Agriculture (Esalq /USP). “The h-index is one of the parameters evaluated, but it’s never enough,” adds Marie-Anne Van Sluys, professor at the USP Biosciences Institute and FAPESP assistant coordinator for Life Sciences. According to her, the popularity of the h-index helped convince Brazilian researchers of the importance of publishing results in indexed journals. “But we must be careful not to create an addiction to numbers,” she says. More important than the h-index, says Van Sluys, is a publication’s context. “Some citations refer to advances in technology, some to advances in knowledge, and others to observations of phenomena. Depending on the type of proposal submitted, this information is particularly relevant to the assessment. And you also need to see how the h-index evolved within the context of a researcher’s career. If the impact is the result of a single article or all of a researcher’s work, this is an important factor,” says Van Sluys.

Confidence

According to Carlos Eduardo Negrão, FAPESP assistant coordinator for Life Sciences, the h-index is a tool to evaluate researchers in physiology and medicine, but cannot be used in isolation. “It is an index that helps determine the impact of the studies published by a researcher and if he focuses on a few or many projects,” says Negrão, who is a professor at the USP School of Physical Education and Sports and director of the Cardiovascular Rehabilitation and Physiology of Exercise Unit of the Heart Institute (InCor). “It is also important to analyze the impact of the journals in which the articles are published and consult the Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge, to check the researcher’s total number of citations. It is also interesting to check how the researcher is seen in our scientific community, that is, his CNPq level. This set of information gives me more confidence that I am performing a fair assessment.”

For proposals in the area of computer science, a concern of the assistant coordinator for Science and Engineering, Roberto Marcondes Cesar Júnior, professor at the USP Institute of Mathematics and Statistics, is how to evaluate the scientific articles presented in certain international conferences, such as the International Conference on Computer Vision. “Use of the h-index in computer science is similar to its use in the hard sciences, but the best journals have an impact similar to that of the articles at this conference, which is indexed in international databases,” he says. He claims that the h-index is useful for measuring a researcher’s success, his interactions with other groups and the impact of his research. “But the most important aspect is always the proposal. The ideas are more important than the numbers,” he says.

For proposals in the area of computer science, a concern of the assistant coordinator for Science and Engineering, Roberto Marcondes Cesar Júnior, professor at the USP Institute of Mathematics and Statistics, is how to evaluate the scientific articles presented in certain international conferences, such as the International Conference on Computer Vision. “Use of the h-index in computer science is similar to its use in the hard sciences, but the best journals have an impact similar to that of the articles at this conference, which is indexed in international databases,” he says. He claims that the h-index is useful for measuring a researcher’s success, his interactions with other groups and the impact of his research. “But the most important aspect is always the proposal. The ideas are more important than the numbers,” he says.

An important side effect of the widespread adoption of the h-index and other indicators based on citations of scientific articles is that it begins to exert influence on the publishing culture of various areas of knowledge in Brazil. In a study published in 2011, Rogério Mugnaini, professor at the USP School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities, and his master’s degree student, Denise Peres Sales, mapped the use of citation indices and bibliometric indicators on Brazilian scientific assessment. They observed that the h-index is used by the Coordinating Agency for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes) as a criterion to define the highest level of scientific journals in various fields, in its Qualis system. Capes weighs these publications more strongly when assessing research groups, making them a prime target when researchers are deciding where to submit their papers.

In the case of dentistry, only journals with an h-index greater than 52 are classified as level 1-A in the Qualis system. In nursing, journals in level 1-A have an h-index of at least 15. In administration, the limit is an h-index of 5. The Web of Science and Scopus databases, which adopted Hirsch’s methodology for evaluating the production and impact of journals, provide periodical h-indices—a publication with an h-index of 50 has had at least 50 articles with at least 50 citations each in a given period. An important finding in Mugnaini’s study is the broad use of citation indices (Journal Citation Reports)—particularly the impact factor (IF)—for evaluations in most areas. The IF is a measure that reflects the average number of citations of papers published in a given journal. IF values range from 0.5 in areas such as geography, administration, accounting and tourism, to 6 in areas such as astronomy. The biological sciences require an impact factor over 4; medicine, 3.8, agronomy, 2; engineering, between 0.8 and 1; and mathematics, 0.95.

Maturation

“The widespread use of citation indices includes areas which have a weaker tradition of publishing in international journals, such as the humanities and applied social sciences which, although not based on an indicator, require indexing of journals in international indices,” says Mugnaini. “Capes plays a phenomenal role with its Qualis system by involving researchers from across the country and ensuring the quality of graduate programs. But what it tells researchers is: the goal is for everyone to publish in international journals with a high impact factor,” he says. In his opinion, what happens in some areas is the acceleration of a maturation process, with researchers trying to publish increasingly in high impact journals. In other cases, however, it is not a natural evolution. “You cannot expect sociology to undergo an internationalization process similar to that of physics. In parallel, there must be mechanisms that allow us to look at a national journal, published in Portuguese, and say: this journal is good. Citations and the h-index will not tell us this,” he says.

An article published in the July 2012 issue of the journal Perspectivas em Ciências da Informação [Perspectives on Computer Science] performed a comparative analysis of the scientific production of CNPq productivity stipend recipients at the 1-A and 1-B levels, which are the top of the scale, in four different fields of knowledge—and observed what may be a behavior change in the humanities. The study, carried out by Ricardo Arcanjo de Lima, Lea Velho and Leandro Innocentini Lopes de Faria, showed that in physics and genetics, areas in which there are strong communities accustomed to publishing in international journals, there was a correlation between a researcher’s h-index and her academic status. In the case of physics, the average h-index for a researcher at level 1-A was 13, and at level 1-B it was 11. However, in genetics, the average h-index for a researcher at level 1-A was 15, and at level 1-B it was 11. In agronomy, the average for a researcher at level 1-A was 7, and at level 1-B it was 6. Sociology produced a surprise. “We expected an h-index of zero, because publishing practices tend to avoid international journals, with a clear preference for publication in books,” says Arcanjo, who is an analyst at Embrapa and last year completed a doctorate in science and technology policy at Unicamp. The h-index was zero for 1-A researchers, but reached 1 for 1-B, which includes younger researchers. “The pressure on researchers may be changing practices in this area in Brazil,” he says.

According to Rogério Meneghini, the case highlights the increasing pressure to deliver knowledge in the humanities. “The dynamics of scientific production are different now,” he says. He notes, however, that the difficulty in publishing in international journals is generating an exaggerated increase in the number of journals in the humanities in Brazil. “As the number of graduate courses in the humanities is growing at a faster rate than in other areas, there has been an uncontrolled increase in periodicals in Brazil. Today, the country has about 5,000 journals. Of the journals requesting inclusion in the SciELO database, humanities accounts for up to 80%,” says Meneghini.

Republish