Léo RamosDuring a meeting in his office in early January, Dr. Euripedes Constantino Miguel, a psychiatrist, interrupted the conversation for a few seconds, stood on a chair and reached to the top of a bookshelf to retrieve two thick volumes of the book Clínica psiquiátrica (Psychiatric Clinic), which he edited in 2011 with two other professors at the University of São Paulo (USP) Institute of Psychiatry. “Here’s a summary of our group’s contribution to the understanding and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder,” he said, while he placed two volumes on the table amounting to 2,500 pages and almost six kilos of paper. At the most recent proceedings of the Psychiatric Clinic Congress, physicians and psychologists who participated in the session How I treat received copies of the book and a password to take an online continuing education course coordinated by Dr. Miguel’s team. “The first year there were 1,200 registrants, the second 2,000 and we now expect to have 4,000,” he said. The publication of this and two other works ––Medos, dúvidas e manias (Fears, Doubts and Manias), reissued in 2012, and Compêndio de clínica psiquiátrica (Psychiatric Clinic Compendium), this year –– and the continuing education program offer were a way for him and his group to reach the highest possible number of mental health experts in Brazil. The goal was to provide them with the latest knowledge produced by Brazilian researchers on a complex, challenging and almost always excruciating disease: obsessive-compulsive disorder, or simply OCD.

Léo RamosDuring a meeting in his office in early January, Dr. Euripedes Constantino Miguel, a psychiatrist, interrupted the conversation for a few seconds, stood on a chair and reached to the top of a bookshelf to retrieve two thick volumes of the book Clínica psiquiátrica (Psychiatric Clinic), which he edited in 2011 with two other professors at the University of São Paulo (USP) Institute of Psychiatry. “Here’s a summary of our group’s contribution to the understanding and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder,” he said, while he placed two volumes on the table amounting to 2,500 pages and almost six kilos of paper. At the most recent proceedings of the Psychiatric Clinic Congress, physicians and psychologists who participated in the session How I treat received copies of the book and a password to take an online continuing education course coordinated by Dr. Miguel’s team. “The first year there were 1,200 registrants, the second 2,000 and we now expect to have 4,000,” he said. The publication of this and two other works ––Medos, dúvidas e manias (Fears, Doubts and Manias), reissued in 2012, and Compêndio de clínica psiquiátrica (Psychiatric Clinic Compendium), this year –– and the continuing education program offer were a way for him and his group to reach the highest possible number of mental health experts in Brazil. The goal was to provide them with the latest knowledge produced by Brazilian researchers on a complex, challenging and almost always excruciating disease: obsessive-compulsive disorder, or simply OCD.

Over the past five years the group led by Dr. Miguel has published at least 70 scientific articles, describing a series of advances that help to better understand the most common characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder and other psychiatric disorders that may accompany and aggravate it throughout a person’s life. Aided by neuroimaging techniques, researchers have obtained evidence that the two internationally recommended forms of treatment to alleviate the symptoms of OCD –– cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressants –– act differently in the brain, in both cases interfering with the activity of the neuronal circuit presumably involved in the problem. They also demonstrated that an extreme alternative, brain surgery that permanently interrupts communication between parts of the neuronal circuit, which in Brazil has only been done experimentally, helped control very severe symptoms of OCD in half the cases where neither medication nor therapy had been effective.

Another important contribution, perhaps even more interesting for those who have OCD, is the finding that, in mild to moderate cases, treatment results with medication are similar to the effects of psychotherapy. In OCD, the most commonly used drugs are antidepressants that inhibit serotonin reuptake, and the preferred form of psychotherapy is cognitive behavioral therapy. What is most important, the researchers say, is to treat the problem continuously. It is clear from monitoring 158 people with OCD over a period of two years that the longer the treatment lasted, the more the symptoms receded. “This work shows that, regardless of the treatment used at the beginning, the important thing is to keep it going, because it takes time for improvement to appear,” says Roseli Shavitt, a psychiatrist and co-author of the study and coordinator of USP’s Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders Project (Protoc). “OCD is a chronic disease for which there is no easy solution,” says Juliana Diniz, another of the team’s psychiatrists. “In order to produce encouraging results, the treatment must last at least a few months, often years, and it is not uncommon for it to last a lifetime,” she says.

Known for exaggerations and oddities such as those exhibited by Jack Nicholson’s character in the movie As Good as It Gets –– he washed his hands all the time, using a new bar of soap each time, and avoided touching people for fear of being contaminated –– OCD is a relatively frequent psychiatric problem. Studies indicate that in several countries the problem affects 2% to 3% of the population, a proportion that can vary according to region or research method. This rate, however, could even be a bit higher. Some years ago Dr. Laura Andrade’s team (Andrade is also a USP psychiatrist) conducted a survey in which they personally interviewed about 5,000 residents of the São Paulo metropolitan area. Published in 2012, the study found that 4% of the participants had experienced obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the year prior to the survey –– a very significant rate, although lower than the rate of depression (11%) and different forms of anxiety (19%).

Known for exaggerations and oddities such as those exhibited by Jack Nicholson’s character in the movie As Good as It Gets –– he washed his hands all the time, using a new bar of soap each time, and avoided touching people for fear of being contaminated –– OCD is a relatively frequent psychiatric problem. Studies indicate that in several countries the problem affects 2% to 3% of the population, a proportion that can vary according to region or research method. This rate, however, could even be a bit higher. Some years ago Dr. Laura Andrade’s team (Andrade is also a USP psychiatrist) conducted a survey in which they personally interviewed about 5,000 residents of the São Paulo metropolitan area. Published in 2012, the study found that 4% of the participants had experienced obsessive-compulsive symptoms in the year prior to the survey –– a very significant rate, although lower than the rate of depression (11%) and different forms of anxiety (19%).

Unwanted thoughts

But OCD is not merely common; but it can also be more serious and more complex than the way it is portrayed in movies. Those who have OCD are continually plagued by unwanted thoughts (obsessions) that invade the mind and, as much as those affected try to avoid them, they generate a lot of anxiety and irrational fears. Examples include fear of a viral infection by touching a doorknob, or horrible doubts, such as forgetting to turn off a gas stove. In most cases, but not always, the obsessions are followed by an uncontrollable urge to repeat certain mechanical and mental rituals (compulsions) –– for example, washing hands until they bleed, checking dozens of times to make sure a gas stove is turned off or counting numbers or praying –– all of which help to reassure. These thoughts and rituals often consume several hours of the day. Diagnostic medical manuals classify this as OCD when this time exceeds one hour, with or without intense suffering. In most cases, they interfere with work performance and socializing with family and in relationships with friends. It’s a very different life from the one lived by those who are neat and like to always have clean hands or by people who are cautious and turn to see if the front door is really closed or even by those who are organized and prefer to keep shirts in a wardrobe sorted by color.

From a medical point of view, what is now known as OCD began to be studied more rigorously in the 19th century in France, Germany and England under different names. And it has been “successively explained as a disorder of the will, intellect and emotions,” says Dr. German Berrios, a psychiatrist and Peruvian historian at Cambridge University, in the book A History of Clinical Psychiatry, published in 2012 by Escuta Press. As he developed his theory of how the mind works, the Austrian physician Sigmund Freud sought to explain the psychological mechanism that psychoanalysis calls obsessional neurosis. Initially, Freud interpreted obsessional neurosis as a conflict between the conscious and the unconscious, resulting from the repression of sexual desire. Unlike hysteria, in which energy could mysteriously jump from mind to body, for example, causing paralysis of a limb, in obsessional neurosis that energy would remain in the psychic sphere. Later, in 1907, when he began to see a patient named Ernst Lanzer, a case that became known as the Rat Man, Freud noticed that in addition to sexual energy, obsessional neurosis also had a strong component of aggression, explains Renato Mezan, a psychoanalyst and professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo. This conclusion helped the Austrian physician to create an entire model of psychic development.

Bottom-up and Top-down

Today medicine explains OCD from a more neurobiological perspective. For physicians, OCD results from the interaction of genetic, environmental and neurobiological factors. This interaction alters the functioning of circuits connecting the outermost areas of the brain — cortex regions linked to processing emotions, planning and control of fear responses — to internal areas such as the basal ganglia and the thalamus, which integrate emotional, cognitive and motor information by regulating responses to the environment. In OCD, the exchange of information between these areas, mainly mediated by the neurotransmitter serotonin, is unregulated. Studies conducted with rodents and humans have suggested that both antidepressants that act on serotonin and cognitive behavioral therapy modify the operation of this circuit. More recently Dr. Marcelo Queiroz Hoexter, a psychiatrist on Dr. Miguel’s team, in partnership with Geraldo Busatto Filho’s group, also from USP, have achieved the most consistent evidence thus far obtained that treatment not only modifies the operation, but also the structure of some brain regions.

Dr. Hoexter selected 38 people with OCD who had never been treated, and after a random selection, assigned them to a therapy group or to a group using the antidepressant fluoxetine. Working in partnership with Rodrigo Bressan’s group of the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp) and researchers from Harvard, he compared brain images taken by MRI at the beginning of the study and after three months of treatment and found that one of the basal ganglia –– the putamen –– had increased volume in people who took the medication and showed improvement. “We believe that fluoxetine alters neuronal plasticity, increasing the connectivity of neuronal circuits in that region and hence their volume,” he says.

Dr. Hoexter selected 38 people with OCD who had never been treated, and after a random selection, assigned them to a therapy group or to a group using the antidepressant fluoxetine. Working in partnership with Rodrigo Bressan’s group of the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp) and researchers from Harvard, he compared brain images taken by MRI at the beginning of the study and after three months of treatment and found that one of the basal ganglia –– the putamen –– had increased volume in people who took the medication and showed improvement. “We believe that fluoxetine alters neuronal plasticity, increasing the connectivity of neuronal circuits in that region and hence their volume,” he says.

For him, these results, along with those of other studies, suggest that the medication promotes a morphological change that starts in the deepest regions of the brain and progresses to those nearest the surface, such as the cortex –– a pattern known as bottom-up. Cognitive behavioral therapy would now do the opposite, first influencing the remodeling of the cortical region linked to consciousness, and then the deepest areas (top-down). “Since the follow-up was only after three months, we were unable to measure changes in the volume of the cortex,” explains Dr. Hoexter. “There is evidence that these changes occur more slowly.”

In some very serious cases in which neither psychotherapy nor medication are effective, Brazilian researchers have taken a more radical step to interrupt the operation of this circuit: an experimental surgery that uses radiation to damage a millimetric region of the internal capsule, a bundle of fibers connecting the basal ganglia to the thalamus (see Pesquisa FAPESP nº 98). Over the past 10 years, Dr. Antonio Carlos Lopes, of the USP psychiatric team, has followed 17 people with refractory OCD, who had not responded to several medications nor years of therapy and went on to have the surgery. About half showed significant improvement after the operation, which caused few side effects –– in general, frequent headache, which was controlled with anti-inflammatory drugs, according to a study submitted for publication to a high-impact scientific journal. According to Lopes, the results indicate that not even the surgery is curative. “It seems to function more as an enhancer of the effects of medication and cognitive behavioral therapy,” Dr. Lopes says.

Complex and heterogeneous

Given that the treatment results are not always promising, Dr. Miguel and his group keep trying to understand OCD. Since 2003 he has coordinated a network of leading OCD experts in Brazil –– now almost 70 collaborators from seven institutions are part of the Brazilian Research Consortium on Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders, the C-OCD – who study the characteristics of this problem in the Brazilian population in order to try to understand its origin and how to treat it more effectively. In a possibly unprecedented effort in Brazilian psychiatry, researchers of the C-OCD conducted in-depth interviews that lasted on average four hours with 1,001 people with OCD in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, Bahia and Rio Grande do Sul.

Léo RamosCompulsions: ritualized movements, such as the repeated washing of hands, relieves anxietyLéo Ramos

Analyzing the information in this sample, the largest collected in the world thus far, they found that only 8% of people with OCD had symptoms exclusively of obsession and compulsion, what they call pure OCD. In most cases, OCD appeared together with at least one other lifelong psychiatric problem: 68% of the study participants suffered from depression and 63% from other anxiety disorders, the most frequent affliction in the general population. Nearly 35% had signs of social phobia, which is characterized by excessive fear of being in public.

The finding that pure OCD is an exception rather than the rule, provided researchers with a clue as to why treatments do not always work as expected. The presence of other diseases –– what doctors call comorbidities –– would indicate a greater degree of impairment of the brain as a whole and possibly of the circuits associated with OCD. In comparison to what occurs in cardiovascular disease, Dr. Miguel says that having pure OCD would be the equivalent of “having hypertension, but not being obese or having diabetes,” something rare in real life. For him, this greater commitment of the nervous system helps explain why the proportion of people with OCD that improve with treatments –– international guidelines recommend cognitive behavioral therapy, antidepressants that act on the neurotransmitter serotonin or a combination of both, which is often more effective –– is lower than initial studies projected.

Previous research that tested each of these treatments alone indicated that up to 60% of patients improved, a rate that was a little more positive when therapy was added to medication. But in general these studies were conducted with people who had the pure form of OCD. When the Brazilian group evaluated these treatments in people with one or more psychiatric disorders associated with OCD, they saw that the response rate fell by half: 30% improved with therapy, 30% with antidepressants and about 50% with a combination of the two treatments. “The existence of comorbidities is the main predictor of whether or not a person will respond to treatment,” says Dr. Miguel. “In that sense, comorbidities are more important than the type of obsessive-compulsive symptoms the person presents, the form of treatment given to the individual or the existence of other cases of OCD in the family (an indicator of genetic predisposition to the problem).”

Based on these results, it is now known that, in some situations, treating the comorbidity is as important as combating the symptoms of OCD. In fact, depression, pure anxiety and social phobia, which may accompany OCD disorders, often prevent people from getting treatment. “Sometimes depression and anxiety are so intense that people are unable to participate in group therapy (a strategy adopted by Protoc) or use medication because anxiety symptoms may temporarily intensify at the beginning,” says Diniz. In such cases, according to the researchers, it is necessary to combat the secondary problem before dealing with the OCD.

EPFL / BLUE BRAIN PROJE CTSimulation shows column of neurons of a tiny portion of the cerebral cortexEPFL / BLUE BRAIN PROJE CT

In addition to disrupting the beginning of treatment, other mental disorders associated with OCD may jeopardize the response to treatment by inducing people to discontinue therapy and medication. In a study published in 2011 in the journal Clinics, Diniz compared the comorbidities of a group of people who completed 12 weeks of treatment with those of another group who dropped out of treatment. Diniz found that cases of anxiety and social phobia were more common among those who dropped out of medical monitoring.

High risk

Comorbidities, the researchers found, also influence an outcome that was little known in cases of OCD: suicide. Dr. Albina Torres, a psychiatrist with the Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) in the city of Botucatu, analyzed the data of 582 patients and found that 36% had already been thinking of taking their own lives, 20% had planned to kill themselves and 11% had actually done so. Dr. Torres also found that the risk of planning or trying to commit suicide was highest among people who, besides OCD, suffered from depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or impulse control disorders. “OCD has always been considered a disorder with a low risk of suicide,” says Dr. Torres. “We have seen that this is not the case.”

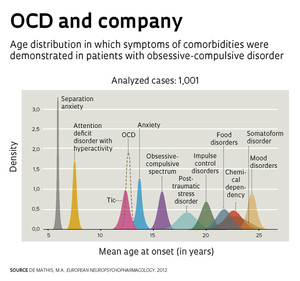

Data provided by 1,001 Brazilian patients led the psychologist Maria Alice de Mathis to investigate the evolution of OCD. Presented in 2012 in the journal European Neuropsychopharmacology, the findings suggest that OCD is really a disease associated with milestone events that occur during a child’s development. In 58% of the cases, the OCD started before age 10. When she analyzed the data from all the patients, Mathis noted that obsessive-compulsive symptoms were not the first to appear: on average, the symptoms emerged between the ages of 12 and 13. The problem that appeared earlier was the fear of being away from parents or home, known as separation anxiety disorder, a form of anxiety that appeared, on average, around the age of 6. A little later, around 7.5 years, there were signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or ADHD.

By comparing the psychiatric disorders presented in childhood with the OCD characteristics at the time of the interviews (many were adults), the researchers reached at least two important conclusions. The first is that people who in childhood showed signs of separation anxiety and later developed OCD were also at greater risk of experiencing post-traumatic stress if exposed to a life-threatening situation (real or imagined). The second is that those with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were more likely to develop substance abuse if they experimented with drugs such as alcohol, marijuana or cocaine. “These earlier disorders can serve as markers of vulnerability to other mental disorders,” says Dr. Miguel. “If we are aware of them, we can prevent further complications from arising,” he says.

More real

According to researchers, a finding that has been confirmed in recent years is that comorbidities are a contributing factor in the already complicated picture of OCD. In 2006, Dr. Maria Conceição do Rosário, a psychiatrist, published an article in the journal Molecular Psychiatry in which she presented the first consistent evidence that, from the standpoint of symptoms, OCD is a very heterogeneous disease: a person can exhibit different types of symptoms with varying intensity. At the time statistical studies were beginning to emerge that attempted to group OCD cases into 13 groups (dimensions) according to the most characteristic symptoms. There are 7 types of obsession, including the fear of harming someone or fear of being contaminated, and 6 types of compulsions, such as having to do repeated checks or having to keep surroundings clean all the time.

This approach, called dimensional, reinforced two observations of clinical practice. The first is that every patient is different. The second is that symptoms are not mutually exclusive, since many people had more than one category of obsession or compulsion. For example, someone with a moderate level of obsession could simultaneously have a more intense fear of contamination and no signs related to fear of harming others. During the internship Dr. Rosário did at Yale University with the group of psychiatrist James Leckman, who is internationally recognized for his work on the mental health of children and adolescents, she began to hone the dimensional strategy.

With Drs. Leckman and Miguel, Dr. Rosário developed an assessment method –– a questionnaire for the diagnosis of OCD known by the initials DY-BOCS. This is the first such scale for assessing the severity of symptoms of different dimensions individually. Besides grouping symptoms by similarity, she provides a more accurate idea of the level of discomfort they cause, how much they interfere with routines and at what level they alter the perception the person has of himself or herself. “We managed to create a representation of OCD much closer to reality than we thought we would,” says Dr. Rosário, who coordinates Unifesp’s Psychiatric Unit for Children and Adolescents and is a member of the C-OCD.

Although it is far from representing the full complexity of OCD, this method of interpreting the manifestations of the disorder, according to Dr. Rosário, has been helping mental health experts to rethink the goal of treatment. “Instead of having a goal to eliminate all symptoms, the goal is now to reduce those most upsetting to the individual,” she says.

Despite these advances, Dr. Miguel has for some time been thinking that there may be another way to deal with OCD. Instead of waiting for symptoms to manifest themselves and then combat them, it would be better to prevent them from taking hold. How? Taking better care of pregnant women and children, since there is strong evidence that OCD, and other psychiatric problems, are a disorder of neurodevelopment. In thinking about this, he and Dr. Luiz Rohde, a psychiatrist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, have begun studies in which pregnant women and their children will be followed over the years with the aim of identifying factors that increase the risk of developing OCD. “We want to do in psychiatry what other areas of medicine, such as cardiology, have been doing for some time,” says Dr. Miguel. “Identifying risk factors in order to intervene early and prevent development of the disorder.”

A dynamic map of the brain

In his February 2013 State of the Union address to the US Congress regarding national priorities, President Barack Obama stated that researchers are mapping the brain and went on to say that in order for this and other endeavors in science and technology to succeed, investments must reach levels not seen since the era of the space race. Researchers took from this speech a commitment to support the Brain Activity Map project.

Proposed in mid-2012 by neuroscientists from the United States and Canada in an article published in the journal Neuron, it is on the order of a Big Science project, with initiatives involving much of the scientific community, as well as public and private institutions, and focuses on a specific question. In this case, an extremely ambitious goal: understanding how the brain works.

In order to do this, recording the activity of each neuron of all neuronal circuits over a period of time is the suggested procedure. It is quite complex, involving major technological challenges. The techniques available today only enable the collection of information from a few cells, and these networks may involve millions of neurons, each making thousands of connections. The operation of these networks, it is believed, must result from a complex interaction, something bigger than the sum of its parts.

This project would require a large-scale effort and enormous investments, similar to the sequencing of the human genome, which from 1990 to 2003, consumed $3.8 billion. According to the New York Times, it is anticipated that the project will be included in the budget proposal that Obama will submit to Congress this month for approval.

In the article in Neuron, the group led by A. Paul Alivisatos,

of the University of California at Berkeley, believes this is a doable task, which could lead to a better understanding of brain activity and how certain diseases arise. And, who knows, perhaps lead to more effective ways to combat them.

There is no guarantee that the project, if approved and put into effect, will result in the hoped-for medical advances. Many genome promises did not materialize because gene functioning is more complex than initially imagined. But it is expected that, in addition to expanding our understanding of the brain, it will generate innovation and jobs –– every $1.00 invested in the genome project generated $141.

Another major project in this area has gained significant momentum in Europe. In January the European Commission selected the Human Brain Project as one of its flagship projects: an ambitious initiative with visionary goals that should pave the way to technological innovation and economic opportunities.

Involving the participation of 80 institutions from Europe, the United States and Japan, this project, scheduled to last 10 years and cost €1.19 billion, aims to gather all knowledge produced about the brain and, using supercomputers, recreate the brain virtually and reproduce how it works.

Projects

1. National Institute for Developmental Psychiatry: a new approach to psychiatry focusing on our children and their future (2008/57896-8); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Coordinator Euripedes Constantino Miguel Filho/IPq-USP; Investment R$5,239,411.72 (FAPESP).

2. Phenotypic, genetic, immunological and neurobiological characterizations of the obsessive-compulsive disorder and their implications for treatment (2005/55628-8); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Coordinator Euripedes Constantino Miguel Filho/IPq-USP; Investment R$1,622,015.67 (FAPESP).

Scientific articles

MATHIS DE, M.A. et al. Trajectory in obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidities. European Neuropsychopharmacology. August 22, 2012.

HOEXTER, M.Q. et al. Gray matter volumes in obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after fluoxetine or cognitive-behavior therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. v.37 (3), p. 734-45, February 2012.

TORRES, A.R. et al. Suicidality in obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and relation to symptom dimensions and comorbid conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. v. 72 (1). January 2011.

ROSÁRIO-CAMPOS, M.C. et al. The dimensional Yale – Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): an instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry. v.11, p.495–504. 2006.

MIGUEL, E.C. et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder phenotypes: implications for genetic studies. Molecular Psychiatry. v.10, p.258-75. 2005.