Energy rationing, poor water supply, and to top it off, a combo of three outbreaks: measles, acute diarrheal disease, and COVID-19. This was the complex situation facing Amapá when veterinarian Wildo Navegantes de Araújo, professor of epidemiology at the University of Brasília (UnB) and consultant to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), a branch of the World Health Organization (WHO), arrived in the state on November 16. “Things are very complex there,” Araújo told Pesquisa FAPESP in an interview on a Friday night at around 10 p.m., following several working meetings. He was in the state to join up with two other members of a PAHO public health emergency response group.

With nearly 20 years of experience studying epidemics and investigating outbreaks of infectious diseases in the farthest corners of the country, Araújo’s expertise as a field epidemiologist has been vital to helping colleagues from state and municipal health departments battling a health crisis on various fronts in Amapá. Some time ago, he collaborated on the diagnosis and treatment of an outbreak of acute Chagas disease caused by contaminated food in the state of Maranhão, another of a kidney disease known as glomerulonephritis, linked to ice cream eaten in the small mining town of Guaranésia, and a third of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome in Santa Catarina, among others. “My work is a bit like being a detective,” he says. “We follow clues, interview people, and send material for laboratory analysis before proposing the most appropriate responses to an event.”

Araújo, or Wildo, as he is better known, is part of an elite team of field epidemiologists trained by the Health Surveillance Department (SVS) at the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The department’s program, created in 2000, trains professionals to handle outbreaks, epidemics, disasters, catastrophes, and other threats to national or international public health. This year, there were 19 professionals taking the two-year course, known as the Epidemiology Training Program Applied to Public Health Care Services (EPISUS).

The initiative, inspired by the Epidemiological Intelligence Service (EIS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the USA, is part of the Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET), which includes roughly 70 programs and more than 100 countries. Over the course of two decades, the Brazilian program has trained 139 professionals who have helped deal with around 400 outbreaks and public health emergencies.

Although the federal government has minimized the severity of the pandemic since the start, EPISUS graduates, when requested, have been helping municipal and state authorities respond. “There are several ways we can assist; it depends on who asks for help. Our work ranges from creating an information system, to changing laboratory diagnosis components or conducting a full investigation. As soon as a municipality or state asks for help, a team will immediately begin field investigations,” says Araújo, who was a student, technical supervisor, and coordinator of the EPISUS program between 2001 and 2010.

Since the beginning of the novel coronavirus pandemic, the epidemiologist has consulted for nine Brazilian states. “I have never seen an epidemic that is so much work to fight. Not from a technical point of view, but in terms of containing the collateral damage caused by fake news and the politicization of technical processes.”

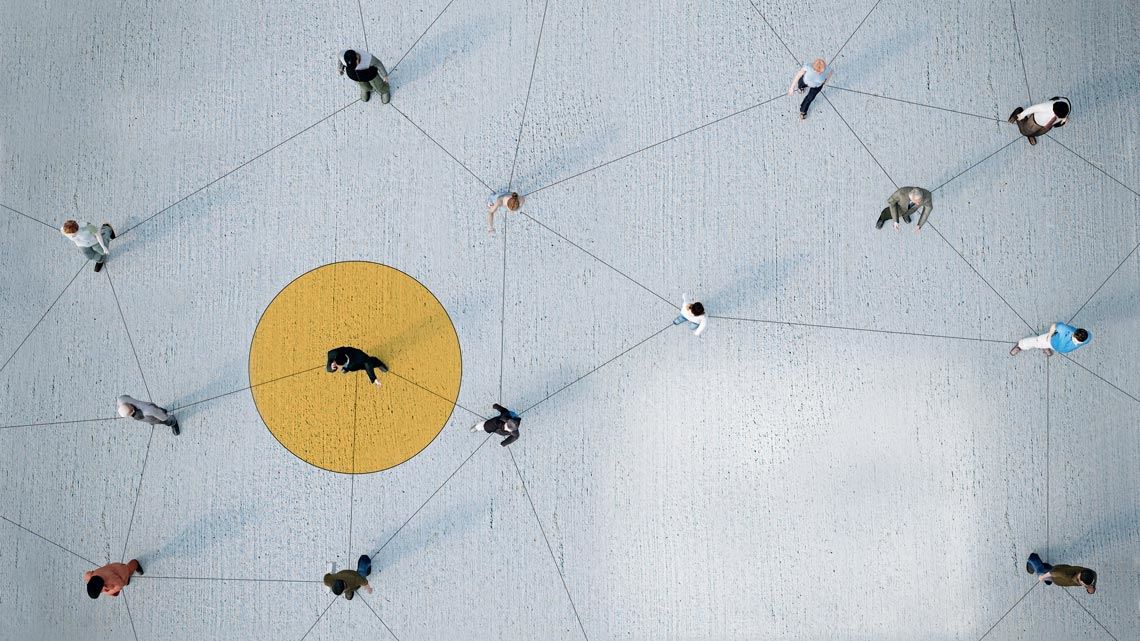

One of the approaches advocated by the PAHO and WHO for tackling the pandemic is contact tracing, a long-established public health and epidemiological surveillance method used to combat infectious diseases, including yellow fever, measles, dengue, and HIV. “We have programs in Brazil to combat health issues for which this activity is essential,” explains physician Expedito Luna, from the Department of Preventive Medicine at the School of Medicine (FM) of the University of São Paulo (USP), former director of the Epidemiological Surveillance Department at the Ministry of Health. “Tuberculosis, for example, as well as leprosy, a bacterial disease that is transmitted slowly, mostly at home. When we identify patient zero, which we call the index case, we have to look for people with whom they have had close contact. They are usually individuals who live in the same house.”

Local primary care teams from the Brazilian public health service (SUS), including family doctors, nurses, nursing technicians, and community health workers are usually responsible for this activity, using phone calls and home visits to identify, treat, and advise people who may have had contact with confirmed cases of infectious diseases, thus breaking the chain of transmission. More complex cases, such as meningitis or orthohantavirus, a zoonosis caused by wild rodents, require actions coordinated at the state and federal levels.

Experts generally agree that the potential scale of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been underestimated by federal and many state authorities in Brazil. One of the highlighted errors was the decision to only respond to serious cases, without investing in epidemiological surveillance in an attempt to break transmission chains. “We missed our chance to stem the spread, despite the SUS’s far-reaching nationwide network. The primary care structure itself was marginalized in the early stages of the epidemic,” reports Luna. “Many health centers have had to close due to a lack of personal protective equipment.”

The situation in Brazil is in stark contrast with what occurred in South Korea. China’s neighboring country invested—and is still investing—heavily in epidemiological surveillance, especially in testing to confirm diagnoses and tracing contacts to contain the spread. Earlier this year, South Korea’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention was granted new powers and autonomy to act as the “control tower” in combating SARS-CoV-2, according to a 238-page document published by the South Korean authorities in October laying out the details of Seoul’s response. New laws were passed to allow the formation of public-private partnerships in the medical field and to allow authorities to collect data for tracing the contacts of infected individuals.

Contact tracing is central to South Korea’s strategy for reducing or eliminating the risk of transmission from infected people with mild or no symptoms of COVID-19. In addition to the health workers, police officers, and members of the ministries of Health, Justice, Transport, and Science & Technology, employees of credit card companies and telephone operators are also part of this endeavor.

Chung Sung-Jun / Getty Images

A health professional performs a COVID-19 test at Seoul test center in South KoreaChung Sung-Jun / Getty ImagesWhenever a person tests positive for SARS-CoV-2 via a RT-PCR test, their movements are recorded from between two days prior to the onset of symptoms—or prior to the test, if the patient is asymptomatic—until their self-isolation start date. Patients are interviewed and their medical history, cell phone GPS records, and credit card purchase history may be analyzed, as well as CCTV footage from public areas when needed, all to establish exactly where they traveled while infected. “This allows us to reduce the time consumed by the investigations,” stated the authorities in the document.

Contacts of confirmed cases must self-isolate for 14 days, without leaving the house or meeting other people. They are monitored twice a day by government officials, who check for symptoms such as fever, cough, and shortness of breath. They also have to download a self-isolation mobile application. If they are not able to stay alone in a room or do not have a cell phone, they are invited to temporarily move somewhere else for the isolation period. Anyone who refuses to go or violates any of the other rules must wear an electronic wristband for monitoring. The fine for breaking the rules is greater than US$8,500 and can even result in a custodial sentence.

Another technological tool adopted by South Koreans is the KI-Pass, a system through which people visiting high-risk locations, such as bars and fitness centers, are required to scan an individual QR code at the entrance. The system helps trace contacts should anyone who visited the establishment later test positive. According to the authorities, the information, which is anonymous and deleted 14 days after exposure of the last contact with confirmed cases, is shared with the population.

Eliseu Waldman, a physician and a professor from the Department of Epidemiology at USPs School of Public Health (FSP), believes that even if the federal government had not abdicated its role of coordinating the fight against the epidemic, and even if there was no technological bottleneck at public laboratories, it would be highly unlikely to see a response in Brazil like that seen in many Asian countries.

“The results that China and Korea have achieved are not reproducible in other cultures, even if they have the organization and technology needed,” says Waldman. “Europeans, Latin Americans, and Africans do not usually respond so homogeneously to recommendations or orders from the State.”

Even to be implemented locally, contact tracing would require resources that are not always available in Brazil and would be difficult to put into practice due to privacy concerns. Even if the information is anonymous and quickly deleted, in many countries the idea of providing credit card and cell phone data or giving access to surveillance cameras would be difficult to accept.

“When the number of cases is very high, you can no longer use this approach,” points out Ester Sabino, from the Institute of Tropical Medicine (IMT) at FM-USP. A contact tracing program in São Caetano do Sul, to be carried out via a partnership between IMT and the Municipal University of São Caetano do Sul (USCS), was never started due to a lack of resources. “We need to lower the number of infected people before it will be possible to do this type of work again. And even then, it would require a major effort,” says Sabino.

USP physician Expedito Luna believes that despite the difficulties, it is not too late to start contact tracing in the country. “Brazil is not homogeneous. Tracing could start in small towns where there are fewer cases, and gradually expand to larger cities. This is what is being proposed by the president-elect’s team in the United States,” he says.

One of the most complex and delicate issues related to SARS-CoV-2, and the subject of great interest worldwide, is the investigation into the origin of the pandemic. Only in November, almost a year after the first confirmed cases of COVID-19, did the WHO disclose details of an international mission of disease detectives from several countries that will begin in the Chinese city of Wuhan. “Where an epidemic is first detected does not necessarily reflect where it started,” says the document classified by the WHO as a “final draft” of what they call a global study.

The clues the international investigators are expected to follow include tens of thousands of sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 genome available in the Gisaid public database, including from early reported cases from the Wuhan market where the novel coronavirus was first detected.

Among other things, the WHO and researchers around the world want to know whether it was bats that passed the new virus onto humans or another animal acted as an intermediate host. For now, when, how, and from which animal SARS-CoV-2 first infected humans remains a great mystery.

Republish