“For the first time, in this city, a blood transfusion was performed on a beriberi patient,” announced the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Globo on June 28, 1877. The newspaper — which bears no relation to the current newspaper by the same name — documented a moment in history where the use of a medical treatment technique caused deaths before the current era’s improvements were made, greatly reducing the risk of adverse reactions and disease transmission.

Beriberi is the result of a lack of Vitamin B1, found in foods such as meat and beans. The disease had left a woman in “a truly moribund state,” according to the press, and, in an attempt to save her, physician Antônio Felício dos Santos (1843-1931), of Casa de Saúde São Sebastião, in the neighborhood of Catete, decided to use the Collins Transfusion Apparatus.

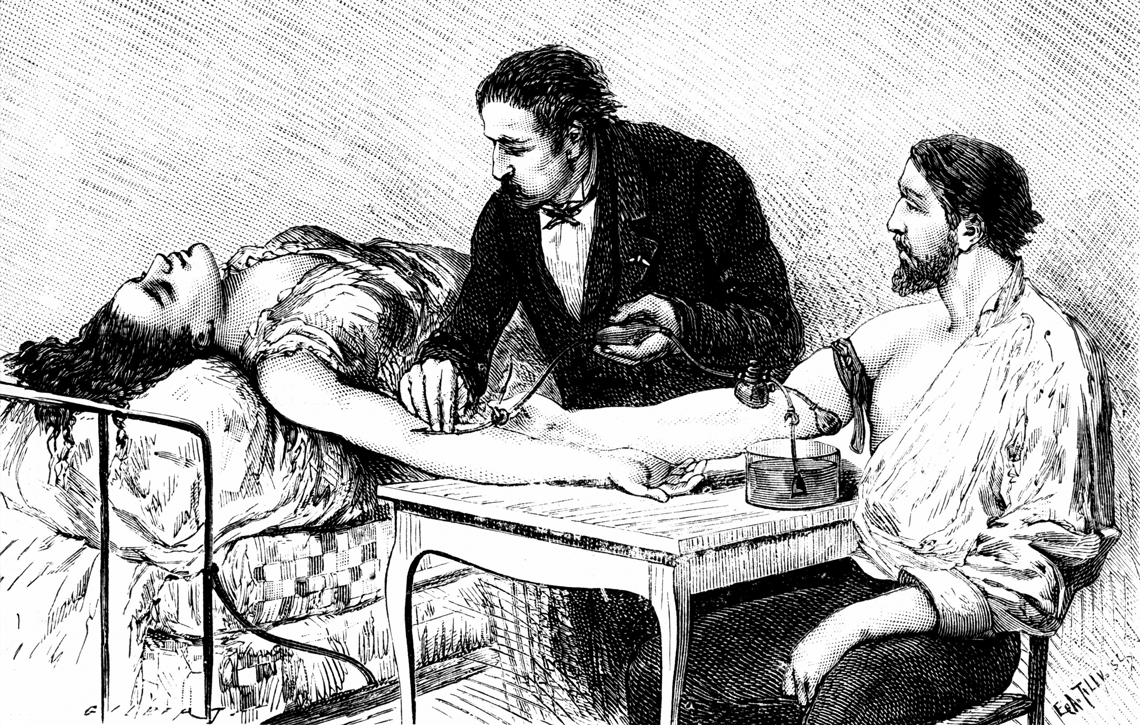

Wikimedia CommonsAn etching from 1882 shows a Geneva doctor performing a transfusion on a woman who lost a lot of blood after birthing premature twinsWikimedia Commons

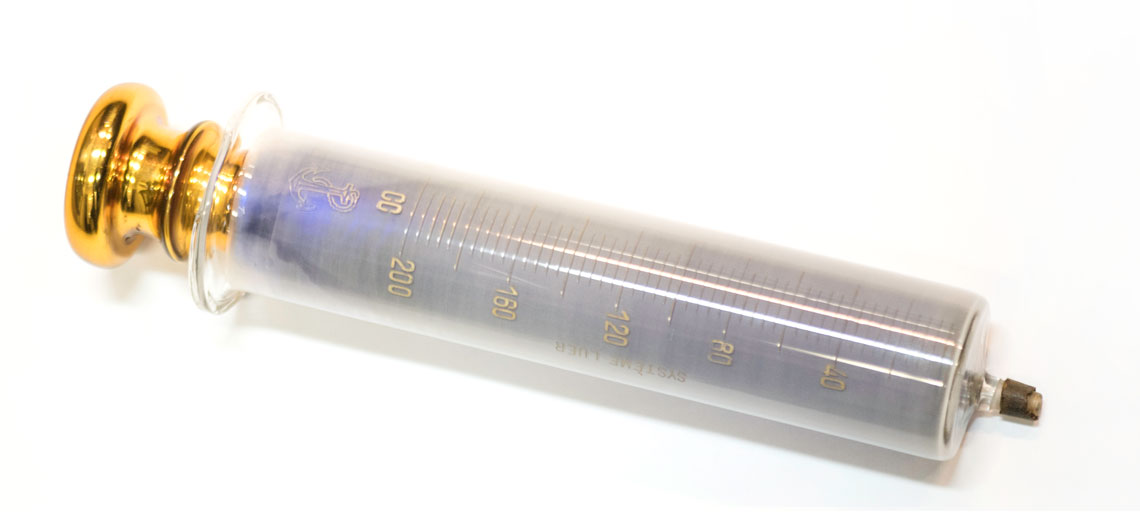

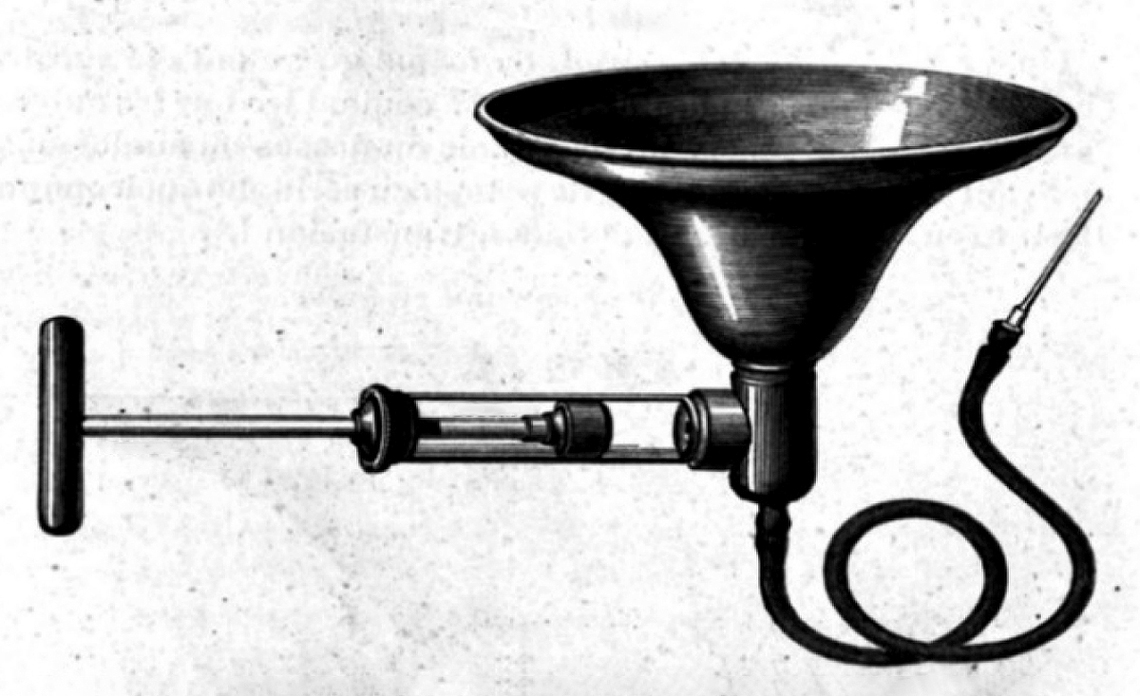

Named after its inventor, French mechanical engineer Anatole Collin (1831-1923), who owned a surgical instrument factory, it consisted of a funnel, into which the blood was poured, connected by a hose to a 300-milliliter (mL) glass container, with a piston at the top. When the piston is pulled back, it collects blood from the funnel. Then, when the piston is pushed in, it moves a floating metal sphere preventing the blood from flowing back, sending the blood through the hose on the other end, connected by a needle to the vein in the patient’s arm. Presented at the National Academy of Medicine in Paris on December 8, 1874, the invention was adopted by the French Army and distributed worldwide.

The woman received 50 mL of blood donated by her husband and died five minutes after the transfusion. Her death was attributed to her grave condition. Santos was a member of the Imperial Academy of Medicine, but does not appear to have reported his experience to his colleagues, as was customary.

“In the history of blood transfusion, there is a lot of omitted information. There should have been numerous accounts of experience with the equipment, but records of its use are rare,” says pharmacist Ana Cláudia Rodrigues da Silva, of Fluminense Federal University (UFF), coauthor of an article about this topic published in September 2022 in the Brazilian Journal of Development. “How many people must have died from hemorrhaging, for example, during a time in which we didn’t even know the different blood types, which is essential to establishing compatibility between donor and recipient?”

photos.com / freeimagesCollins Transfusion Apparatus: introduced in Paris in 1874 and used in many countries, including Brazilphotos.com / freeimages

Until the early twentieth century, the result of a transfusion depended essentially on luck. There were tragic episodes, such as the attempt to save Pope Innocent VIII (1432-1492), who was on the verge of death as a result of a severe kidney disease. With no other alternatives, his doctors convinced him to drink human blood.

As the story goes, albeit with no proof or details, three 10-year-old boys offered to donate their blood to the pope, in exchange for a ducat coin. The first died after they removed his blood, but the pope showed a slight improvement. Encouraged, the doctors called upon the second donor, removed less blood than they did from the first, but this time the pope ran a high fever, his kidneys stopped working, and he died. The third boy did not need to donate blood, but also died soon after from anemia, which at the time had no diagnosis or adequate treatment.

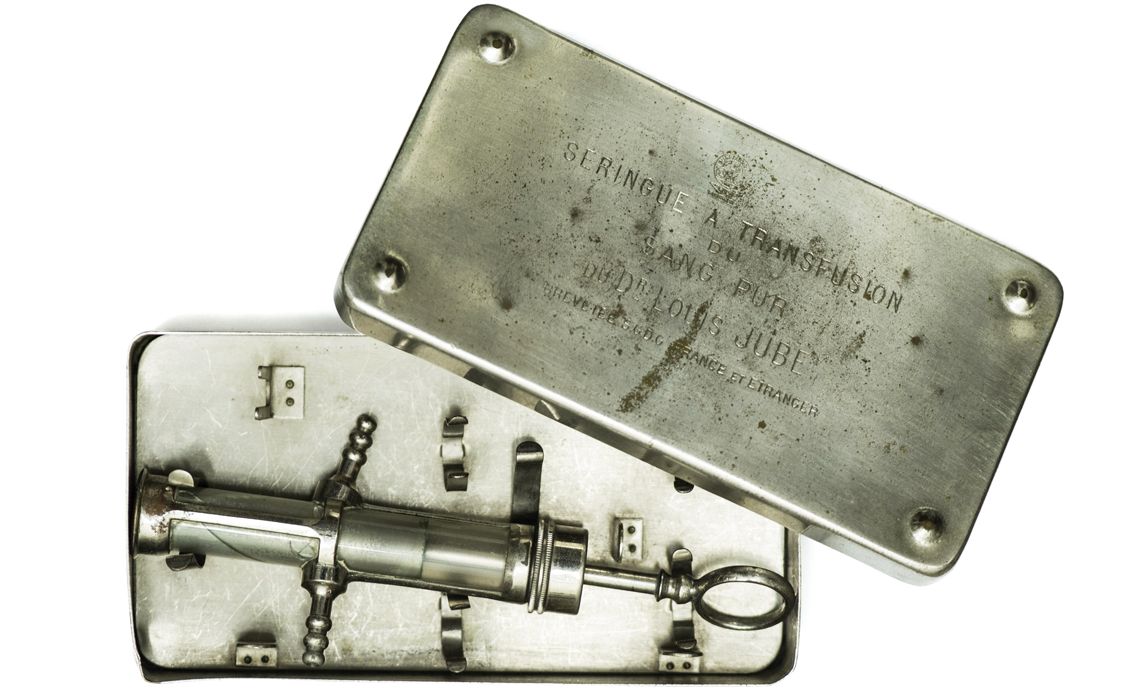

Santa Casa de São Paulo Museum - Reproduction Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPJubé syringe, imported from FranceSanta Casa de São Paulo Museum - Reproduction Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Another unsuccessful experiment, in Paris, in 1678, led to France and England prohibiting — and criminalizing — blood transfusions. In Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1818, obstetrician James Blundell (1790-1878) turned things around when, after experimenting with animals, he performed the first successful transfusion for women with postpartum hemorrhaging. He used a funnel to hold the blood taken from the donor’s vein, which flowed through a hose and entered the recipient through a needle. His technique was limited to extremely severe cases, when death was nearly certain, because the results were uncertain: some patients recovered, but others died.

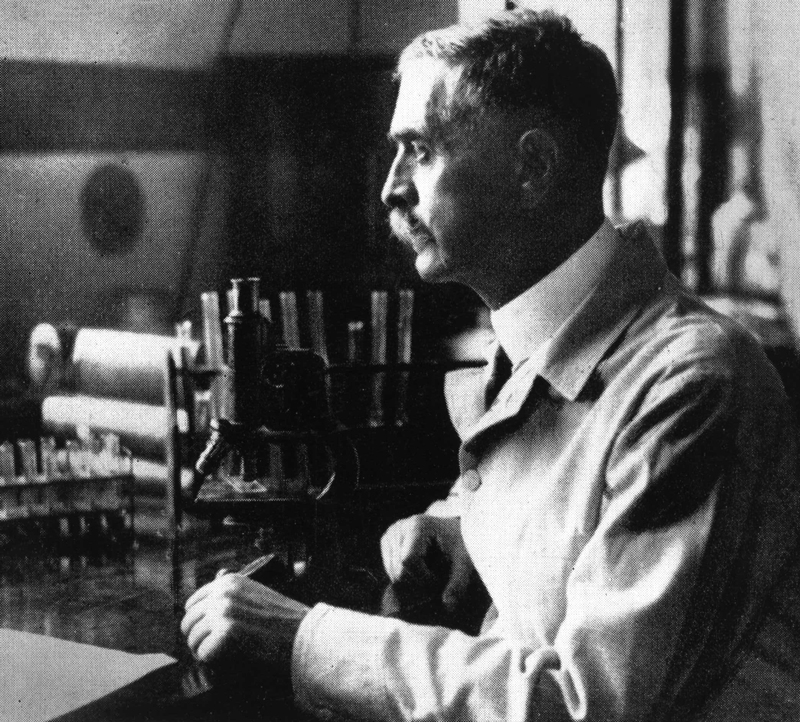

The risks dropped considerably as of 1901. In that year, while investigating the cause of death of patients after blood transfusions, Austrian pathologist Karl Landsteiner (1868-1943), of the Anatomical Pathology Institute of Vienna, then capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, identified the first blood group, the ABO system, consisting of four types (A, B, AB, and O), and characterized by the presence or absence of specific proteins in the red cells or blood plasma. It became clear that the unwanted reactions were the result of the recipient’s defense system attacking the incompatible proteins from the donor. His work earned him the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Historical Museum of FM-USP - Reproduction Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPA transfuser with rubber tubes, created by Brazilian physician José Augusto de Arruda Botelho to transfuse blood directly from the donor to the patientHistorical Museum of FM-USP - Reproduction Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

In 1940, at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, in New York, Landsteiner and North American physician Alexander Salomon Wiener (1907-1976) discovered the Rh factor, an antigen — protein capable of activating the body’s defenses — in the serum of rabbits immunized with blood from a rhesus monkey. People who produced this protein began being called Rh+ (positive) and those who did not, Rh- (negative); Rh+ people could receive blood from both R+ and R- donors, but could only donate to other R+ people.

Years earlier, another serious problem had been resolved: outside of the body, blood coagulated quickly. Working separately and without knowing each other’s findings, in 1914, Belgian surgeon Albert Hustin (1882-1954) and Argentinian doctor Luis Agote (1868-1954) showed that adding sodium citrate prevented coagulation, without harming the patient.

University Of Wisconsin Library Karl Landsteiner in his laboratory at the University of Vienna, where he identified the first blood group, the ABO systemUniversity Of Wisconsin Library

The study conducted by Silva and others recounts that in 1915, inspired by Agote’s work, doctor João Américo Garcez Fróes (1874-1964) performed Brazil’s first successful blood transfusion at Hospital Santa Izabel, of Santa Casa de Misericórdia da Bahia, in Salvador. The patient was 26-year-old domestic worker Maria Salustiana, who was suffering from severe anemia after hemorrhaging following surgery to remove a polyp from her cervix.

Fróes used a device designed by Agote. The donor’s blood was stored with sodium citrate in a container attached to two hoses. A smaller bottle attached to one of the hoses contained a rubber pump that applied pressure so the blood would flow through the other hose to the needle and the patient’s arm. The blood type, though already known, was not tested. Luckily, the blood from the donor — João Cassiano, a hospital orderly, chosen because he appeared to be in good health at the age of 22 — and Salustiana’s blood were compatible.

In 1916, doctor Isaura Leitão de Carvalho (1885?-1928) described this and three other successful blood transfusions, also without mentioning blood typing, performed that very year by Fróes, the advisor for her grad work presented at the Bahia School of Medicine at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). In 2019, hematologist Cristiane Silveira Cunha revisited the records of these stories in her dissertation, presented at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO). “I had to search quite a bit but I visited the outpatient clinic where Isaura worked and found a great-niece, Ana Mary, who kept photos of her,” she recounts.

Cunha also found an account of the indifference with which other physicians reacted to the presentation given by Fróes on May 5, 1918, at Sociedade Médica dos Hospitais da Bahia. A note in the June 29th edition of Brazil Médico highlighted “the undeserved neglect of Bahian work, such as what happened in relation to the blood transfusion he performed, about two years ago, using Dr. Luiz Agote’s method.”

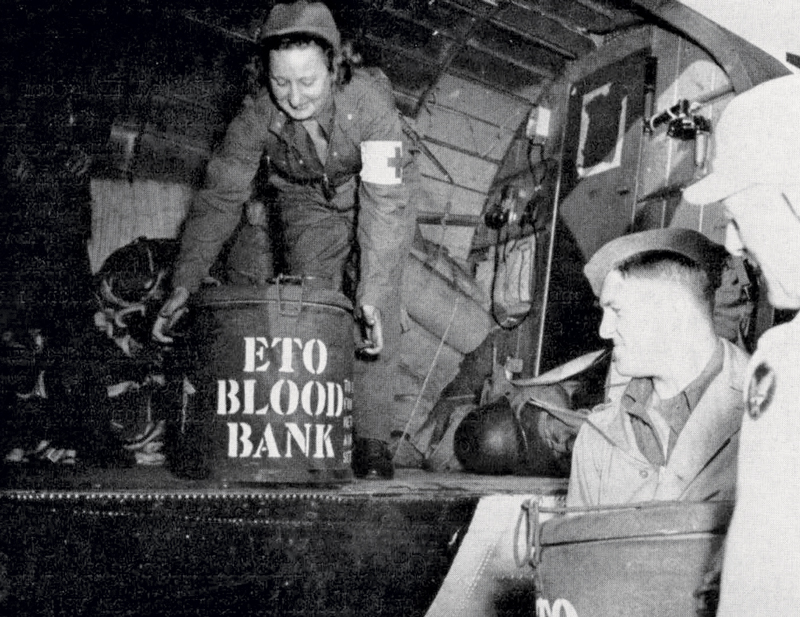

Usa Army

Usa Army

In 1918, without citing Fróes, doctor Augusto Brandão Filho (1881-1957) presented a paper at the Rio de Janeiro School of Medicine — now linked to the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) — on transfusions in children, in which he recounted his own case of a premature baby with gastrointestinal bleeding at the Laranjeiras Maternity Hospital in Rio de Janeiro. The technique became routine, although there are few reports prior to the creation of the Blood Transfusion Services (BTS), in 1933, also in Rio.

In the meantime, some improvements were made. An evolution of Agote’s device, the Jubé syringe — created by French physician Louis Jubé (1899-?) in 1924 — made the job easier by connecting the donor’s arm to the recipient’s arm with two hoses and dispensing with the use of an anticoagulant. Clamps on the hoses ensured that the blood would flow to the correct side. The circuit was vacuum-sealed and easy to sterilize. With access to blood typing reagents, doctors established transfusion services, with records of type O donors, who could donate to all other types. In reality, there was no such thing as donation, since all transfusions were paid for.

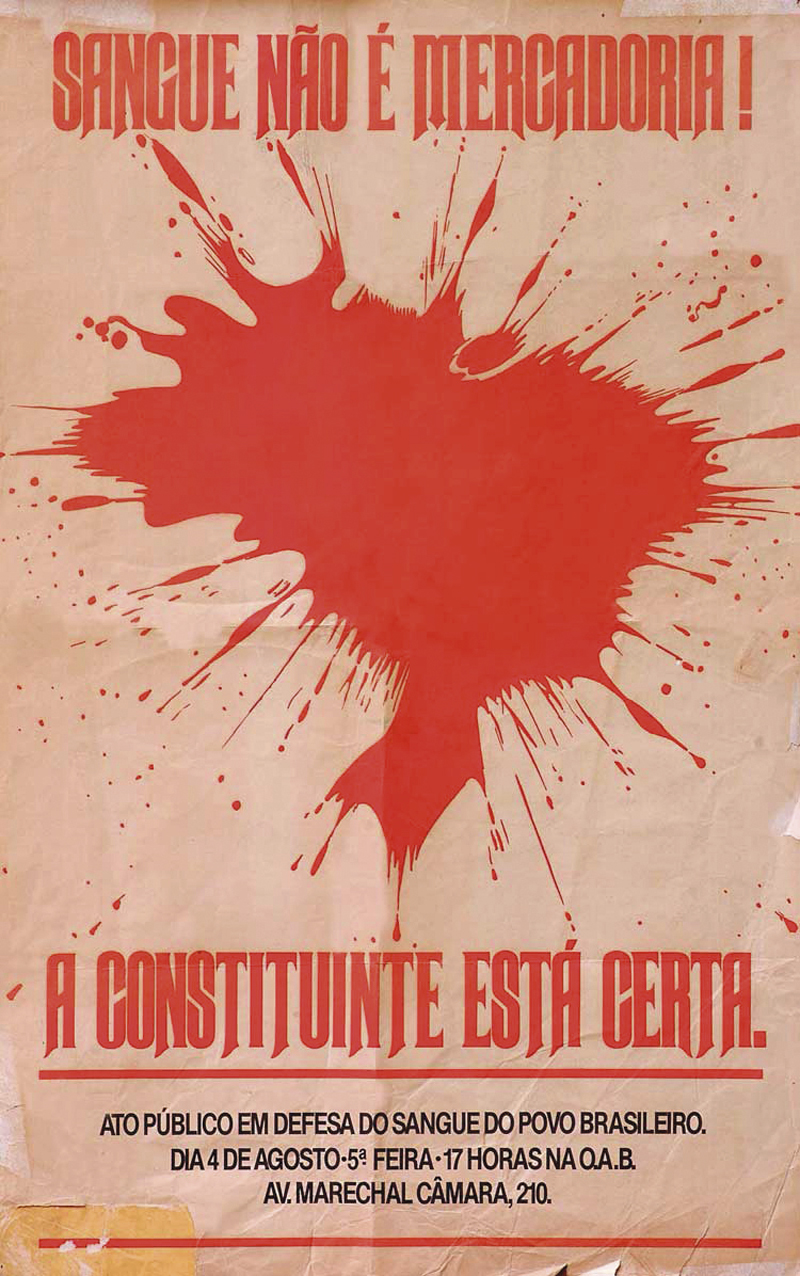

FiocruzA poster for a blood donation campaign, inspired by the Henfil LawFiocruz

The Second World War (1939-1949) prompted the creation of blood banks around the world. In Brazil, the first was established in 1942 at the Fernandes Figueira Institute, in Rio de Janeiro. Simultaneously, hemotherapy became a medical field. Until then, transfusions were conducted by surgeons and obstetricians, while hematology dealt with infectious diseases, such as Chagas disease and yellow fever. Created in 1950, the Brazilian Society of Hematology and Hemotherapy (SBHH) united the two fields.

“Until 1980, paid donations were a way of life. The poorest donated the most, in exchange for a few bucks,” recounts hematologist Nelson Hamerschlak, of Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein. “It was concerning because the agents that caused hepatitis and Chagas disease could be transmitted by blood.” To remedy the situation, in 1979, the SBHH launched a campaign for altruistic blood donation.

On April 30 of the following year, the National Hemocomponents and Blood Program (Pró-sangue) established the Brazilian hemotherapy system, with the creation of blood centers, specialized in collecting, processing, and storing blood and its components. One of its guidelines was that donation was unpaid; another was donor and recipient safety, which the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s put to the test. “The number of cases where the HIV virus, which causes AIDS, was transmitted began to spike dramatically, particularly in patients with hemophilia or those who received several transfusions,” recalls the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) hematologist Carmino Antônio de Souza (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 323). “Unfortunately, we had not established laboratory methods to prevent transmission or treat patients with completely safe products.”

In 1988, the Henfil Law — named after cartoonist Henrique de Souza Filho (1944-1988), who was a hemophiliac and, like his two brothers, contracted HIV from a transfusion — mandated serological tests to detect HIV That year, the Constitution gave the government the power to regulate, supervise, and control blood and its components, such as plasma, and banned its sale.

It was only in 2014 that the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) published the requirements that must be met at any blood center in Brazil. Today, before stretching out their arm to donate blood, donor candidates provide a sample for blood typing (ABO and Rh) and to detect agents that transmit HIV, HTLV1, syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and Chagas disease. Souza celebrates the advances in this long history: “Fortunately, reactions due to incompatibility and the transmission of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa through the transfusion of blood and its components has become very rare.”

Scientific articles

CUNHA, C. et al. Transfusão de sangue no Rio de Janeiro e em Salvador: A tecnologia na virada do século. Cadernos UniFOA. vol. 17, no. 48. apr. 2022.

JUNQUEIRA, P. C. et al. História da hemoterapia no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia. vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 201–7. sept. 2005.

VITORINO, M. et al. Medicina transfusional brasileira: O resgate de uma história. Brazilian Journal of Development. vol. 8, no. 9. sept. 2022.