Léo RamosDeops Archives in São Paulo: a model for truth commissionsLéo Ramos

In early April, the São Paulo State Public Archives launched the web site Memory, Politics, and Resistance, which allows open online access to a total of 1,000,000 searchable images – that is, over 314,000 fichas (index cards listing the subject’s name and personal data, usually linked numerically to his or her police record) and 12,800 police records, all of which were produced by political surveillance agencies in the state of São Paulo from 1924 through 1999, a period that covers two dictatorships (1937-1945 and 1964-1985). Ten percent of the pages of the records preserved at the archives have already been digitized, and this work will proceed in the coming years. The material available online comes from three sets of documents. One is the collection of the Santos Department of Political and Social Order, which comprises over 80 linear meters of documents illegally held at the Santos Police Palace until 2010, when they were retrieved. The archives also hold fichas and police records from the São Paulo State Department of Political and Social Order (Deops) – formerly the main agency of the São Paulo political police, abolished in 1983 – whose collection of 1,173 linear meters of documentation was transferred to the State Public Archives 23 years ago. Lastly, there are documents from the Department of Social Communication (DCS) which took over the duties previously assigned to Deops and was in operation from 1983 to 1999.

The digitization work was supported in part by FAPESP, which allocated R$1,690,000 in funds for the modernization of the archives’ laboratories under the São Paulo State Support for Research Infrastructure program. The Ministry of Justice and the Executive Office of the President also apportioned funds to the initiative. “People can access the site from their homes, there’s no password – it’s all public. This is very important in order to maintain transparency and provide information to the families of the victims of the dictatorship period,” emphasized São Paulo Governor Geraldo Alckmin during the launching ceremony. This endeavor represents a milestone in restoring society’s collective memory of political repression and resistance, and it will play a valuable role in the work not only of historians but also of Brazil’s National Truth Commission and of the state and municipal commissions established to investigate human rights violations. “Our truth commission is the only one in the twenty-first century. We’ll have access to technologies available to none of the world’s previous 40 truth commissions,” stated political scientist Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, coordinator of Brazil’s National Truth Commission.

Léo RamosA planetary scanner, which copies documents without damaging them, was used to digitize documents from the Deops collection retrieved from SantosLéo Ramos

Because Brazil’s truth commissions were set up more than 25 years after the demise of the military regime and many witnesses have died or don’t remember details that could shed light on crimes, the identification of documents is vital to the reconstruction of facts. “These documents should be especially useful in finding the missing pieces of the investigation puzzle for those who died or ‘were disappeared’. This is our primary expectation in regards to these archives,” says political scientist Glenda Mezarobba, consultant and researcher with the National Truth Commission. According to Ivan Seixas, coordinator of the São Paulo Legislative Assembly Truth Commission, documents from the Deops collection have helped the body in its investigative work. He cites the example of the analysis of six books dating from the 1970s, which recorded who entered and who left the Deops headquarters; findings suggest that there were ties between a U.S. diplomat and a Brazilian industry representative, on the one hand, and Brazil’s political repression agencies on the other. The books register frequent visits by the U.S. Consul in São Paulo at that time, Claris Rowney Halliwell, and by Geraldo Resende de Matos, who is listed as an employee of the Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo (Fiesp). Fiesp, however, denies that Matos was ever on its payroll. “These documents reveal the day-to-day routine at Deops,” says Seixas. He points out how digitization of the collection is benefitting municipal-level commissions. “There are already commissions in Santos, Bauru, and Campinas. The ability to have online access to these documents will facilitate the work of the municipal commissions,” he states.

Documents from the Deops collection retrieved from Santos

Digitization will also afford an unprecedented opportunity to cross-reference information. “With documents assembled in a databank, a gamut of information can be cross-referenced, and references to anyone persecuted by Deops can be located expeditiously,” says historian Lauro Ávila Pereira, director of the São Paulo State Public Archives’ Department of Preservation and Dissemination. Advanced programming resources will allow smart searches to be performed on the entire set of documents. “If, for example, we find a certain type of document that presents pertinent information on someone who was politically disappeared, we can do a search for documents of the same type in the hopes of shedding light on other cases,” Glenda Mezarobba says. Mezarobba is part of a sub-group assigned to employ e-science technology to obtain results through data-intensive computing and to explore large digital data sets to track down information that will help elucidate human rights violations. Last year, Mezarobba took a leave of absence from her post as director of FAPESP’s Human Sciences area to work with the commission. Another member of the sub-group is Roberto Marcondes Cesar Júnior, professor with USP’s Department of Computer Sciences and assistant coordinator of FAPESP’s Office of the Science Director. Around 16 million pages of the National Information Service’s (SNI) archives are also being digitized. “It would be ideal if we could digitize every archive in the country. It’s not unusual to find copies of a document that has vanished from one archive in another collection,” says Pereira.

The State Archives’ initiative to make its collection available online is grounded on Brazil’s Freedom of Information Act, which took effect in May 2012 and removed obstacles to the release of documents. Under this law, “documents that speak to conduct that implies the violation of human rights by public agents or at the order of public officials cannot be the object of restricted access.” The collections of repressive agencies began to be transferred to state archives in the 1990s. But with the exception of São Paulo, access was only allowed in most states in the first decade of 2000; even so, searches are often restricted to researchers and family members who can prove their relation to the documents. “In the case of the São Paulo State Archives, we only ask that those who consult the online archives be careful about how they use information concerning a third party’s private life,” says Carlos Bacellar, archives coordinator and professor with the Department of History at USP’s School of Philosophy, Language and Literature, and Humanities (FFLCH/USP). “Privacy can only be unlocked if it helps clarify the facts. If the information doesn’t clarify anything and yet divulges details of someone’s personal life, it is not of social interest.”

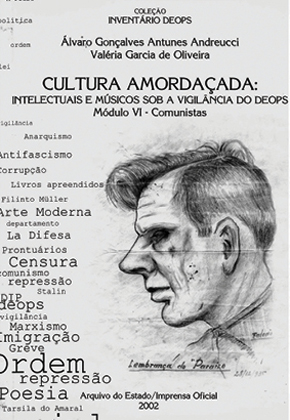

Léo RamosInventories on the Deops collection: training researchersLéo Ramos

The digitization of the complete contents of police records started with the Deops collection in Santos, since researchers and the families of prisoners and the politically disappeared had previously had no knowledge of this set of documents, discovered only in 2010. “It made sense to start with the material from Santos because it was a new find, while people had been exploring the large Deops collection in São Paulo since the mid-1990s,” says Pereira. The recovery of the Santos archive is a curious chapter in the revival of collective memory. In its edition of Friday, February 26, 2010, the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo announced that this collection had been discovered in storage at a police station in the city of Santos, triggering a rapid-deployment police operation. Aloysio Nunes Ferreira, then secretary of the São Paulo Executive Office of the Governor and today federal senator, along with Justice Secretary Luiz Antonio Marrey, ordered technical staff from the State Archives to head to Santos immediately and retrieve the documents. They were worried that the publicity surrounding the discovery would prompt people involved with the dictatorship’s repressive forces to remove compromising documents – a villainy that had resulted in the plundering of a good share of other collections. “We managed to borrow a truck from the Civilian Police, no less, and by 3 a.m. on Saturday morning, all the boxes of documents were in São Paulo,” recalls Pereira. The fichas and police records were in rough shape, and it took over a year to treat and digitize the documents. There are signs that this collection holds documents not available in other archives. For example, it contains a unique set of fichas on custodians and doormen at apartment buildings in Santos who were required to inform the police whenever someone rented an apartment there. “The custodians were forced to serve as informants; they would ask tenants to fill out a form with a list of the residents in their unit,” says Pereira.

Equipment was purchased from abroad to speed up the digitization process. “FAPESP involvement was vital, not only through its funding but also because of the support it gave us in importing equipment, which we acquired much faster than if we had bought it some other way,” says Carlos Bacellar, archives coordinator. By using this equipment, a team of 10 technicians can digitize nearly 2,000 images a day. Two highlights of the purchased equipment are a planetary scanner, which copies documents without damaging them, and another type of scanner used to record the original image on microfilm.

Digitization will play a key role in expanding researchers’ access to archives on political repression. Some historians are already looking into the Deops archives in São Paulo. Maria Aparecida de Aquino, professor with the Department of History at FFLCH/USP, has published five books based on her work to map out and systematize the Deops collection, with the support of FAPESP from 1998 through 2002. The books came out as part of the series “Radiografias do Autoritarismo Republicano Brasileiro” (X-rays of Brazil’s republican authoritarianism), released by São Paulo’s state press. “There was a complex alphanumeric code on each of the 9,626 file folders that we consulted. We deciphered this code with the assistance of a 20-member team of grant recipients, coordinated and monitored by me and two of my doctoral students,” recalls the professor. “We conserved the material, replacing the folders it was in, cleaning it, and inserting neutral paper for protection, and we handed over a fully computerized databank,” she says.

Another professor from the Department of History at FFLCH/USP, Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro, has been making steady use of the archives. In the 1990s Carneiro, who focuses on subjects such as racism and anti-semitism, obtained authorization from the archives to analyze fichas and police records, which she did with the aid of undergraduate research grant recipients and master’s and doctoral candidates. “We created History Workshops at the archives, with up to 60 students working on this material for over a decade. It was a living history lesson,” she says. “More than 40 researchers received their training during this effort, which yielded 10 theses, 8 dissertations, and a number of publications, such as 14 inventories of documents.”

One of the challenges, according to the professor, was deciphering the logic of the repressive agent’s language and determining to what point it expressed the truth and where, exactly, the fiction was devised and inserted to justify intolerance and application of the label ‘political crime’. “The first step was understanding this notion of ‘political crime’, which lent itself to the surveillance, persecution, and imprisonment of an undesirable citizen because of his ideas. A crime of ideas is constituted at the moment that thoughts acquire a physical form – in other words, when it can be identified through the production of knowledge or political propaganda printed in books or pamphlets and confiscated as proof of the crime,” she states. Between 1995 and 1996, Carneiro began using the Deops archives as part of a project funded by the Goethe-Institut about Jewish women expelled from Brazil under the Vargas regime. She then received FAPESP support for two thematic projects that resulted in a series of inventories and the creation of a virtual archive holding documents selected by specific topic.

Under Carneiro’s guidance, a team of 30 researchers manually entered the data from over 185,000 Deops fichas starting in 1999. “At the time we didn’t have any equipment or a database that would let us do an advanced search of the police fichas, so our option was to use manual data entry,” she says. Since 2000, an individual’s ficha can be consulted at the site of Proin, acronym for the São Paulo State and USP Integrated Archives Project. Likewise available on the site are the digitized front pages of the newspapers, pamphlets, and books seized during searches of homes of suspects or the offices of community or political organizations. Under the coordination of Professor Boris Kossoy, of USP’s School of Communication and Arts, Proin put together an inventory of photographs that were confiscated from family albums or produced by the photography laboratory at Deops and then attached to police records and dossiers.

Republish