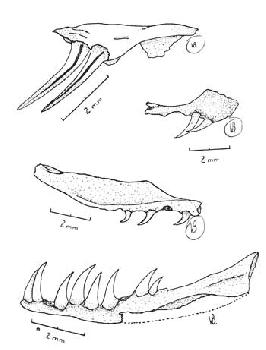

Drawings by Paulo Emilio VanzoliniDetails of reptiles and amphibians drawn by the researcherDrawings by Paulo Emilio Vanzolini

At the age of 10, Paulo Emílio Vanzolini passed the exam which enabled him to enroll in middle school. His father gave him a bicycle as a reward. The boy got on his new bike and rode to Instituto Butantan, on the west side of São Paulo City, where he fell in love with the snakes and decided he would become a researcher. At the age of 14, Vanzolini was already a trainee at the Biology Institute of São Paulo and at the age of 23 he graduated from the University of São Paulo’s Medical School. (USP). During his doctorate studies at Harvard University – where he got his degree in 1951 – Vanzolini decided to explore herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians.

After more than 60 years dedicated to science, the 86-year old Paulo Vanzolini has finally published the book “Evolução ao nível de espécie – Répteis da América do Sul.” The book, which contains more than 700 pages, was published by Editora Beca publishing company with the support of FAPESP. It is a compilation with 47 of the main articles published by the researcher between 1945 and 2004. “We compiled everything into one document to make research studies easier. The book represents my career quite well,” says Vanzolini. “I have always worked in the same line of research, seeking to explain how the enormous diversity of South American fauna came about. All my findings are now published in one book,” adds the researcher, who received an award from New York’s Guggenheim Foundation in 2008 in recognition of his contributions to science. “The publishing of this compilation has a special meaning for FAPESP,” wrote Celso Lafer, president of the FAPESP in a preface to the book. “First of all, it is recognition of Vanzolini’s contribution to the development of zoology; second, it is a way of emphasizing how the story of his life is linked so constructively to the life of FAPESP.”

Miguel Trefaut Rodrigues, a professor at the Bioscience Institute of the University of São Paulo (IB/USP), says that Vanzolini’s research work helped change Brazilian zoology which, up to the mid-20th century, had been mostly dedicated to timely and isolated study of animals. “Vanzolini changed the focus of these studies and started working on the mechanisms of the species from an evolutionary perspective, gathering biological and geo-morphological knowledge and analyzing animals on the basis of the landscapes they lived in,” he says. “In his research work, the systematic study of reptiles and the search for an evolution model able to explain their diversity correspond to inseparable points of the same mental process,” adds Hussam Zaher, current director of USP’s Zoology Museum.

Trefaut points out that for a long time the most widely accepted scientific explanation to justify the biodiversity of biomes such as that of the Mata Atlântica rain forest was that the biodiversity had resulted from long periods of climate and geological stability, which had allegedly provided the appropriate environment for mating and reproduction. At the end of the 1960’s, Vanzolini retrieved concepts that had been initially formulated to explain the different bird species in Europe and proposed his refuge theory, which had been simultaneously and independently proposed by Germany’s Jurgen Haffer. Vanzolini was helped by Brazilian geographer Aziz Ab’Saber in this endeavor.

According to this interpretation, South America had gone through cycles of intense climate variations – more specifically, in the last 1.6 million years. Between 18 thousand and 14 thousand years ago, when the continent was engulfed by the last ice age, geographic niches with tropical forests – the refuges – had been formed because of the cold. These refuges allegedly guaranteed the survival of species that were less accustomed to the cold. When the temperatures went up again, the species were able to abandon the refuges and meet again. “Vanzolini shows that diversity and speciation arose thanks to the formation of isolated islands and frequent changes and not as a consequence of a slow and stable evolution” says Trefaut.

He mentions the articles “Zoologia sistemática, geografia e origem das espécies”, written in 1970, and “The vanishing refuge: a mechanism for ecogeographic speciation”, written in 1981, as two of the outstanding articles in the book. Both articles are directly related to the refuge theory. “The first article is a multi-disciplinary study, written in Portuguese, which provided access to a line of research that had up to then been restricted to the few researchers that spoke English at that time. This article is also a basic article because it contains practical examples, specifying how these refuges were identified,” says Trefaut. The second article proposes a new mechanism to explain how new species arise, with ecological adaptations that differ from those of their ancestors. “Vanzolini was innovative in the sense that he introduced and disseminated in Brazil, by means of his students, a modern view focused on the study of geographic variations, using statistical tools to this end,” Zaher points out.

Starting point

Controversies are also part of Vanzolini’s professional life. Brazilian and international studies that evaluated pollen grains, river and the sediments of rivers and hydrographic basins, have sought not only to challenge but also to deny the refuge theory (see Pesquisa FAPESP nº 129). Vanzolini strikes back and states that no other scientifically convincing explanation has arisen to substitute his proposed theory. “There is no way one can deny that the refuges existed as a climate and ecologic mechanism,” says Trefaut. “The fact is that science always does its best. Perhaps this theory will be studied again or reviewed in 10 or 15 years. Nonetheless, Vanzolini’s contributions have been the starting point,” he adds.

Trefaut also emphasizes Vanzolini’s leading role as the director of USP’s Zoology Museum from 1962 to 1993, when he organized the museum’s collection. “When he took on this position, a little over one thousand specimens had been cataloged. Now there are more than 300 thousand,” he says. According to Trefaut, Vanzolini himself often spent time typing labels and identification forms for the animals in the museum. “His life was dedicated to collections,” he adds. Zaher agrees and adds that Vanzolini “led a team of zoologists who built up one of the biggest and most important neo-tropical zoology collections over the course of many decades.” When commenting on the changes in Brazilian science that he witnessed during six decades, Vanzolini – who is also a renowned composer of popular Brazilian music – does not hesitate to say that the strengthening of the post-graduate educational system, which did not exist when he was a student, has driven Brazil to an outstanding position on the international scenario. “I revere nature. And I had a very rewarding career,” he says. “I can say that I am an entirely fulfilled researcher.”

Republish