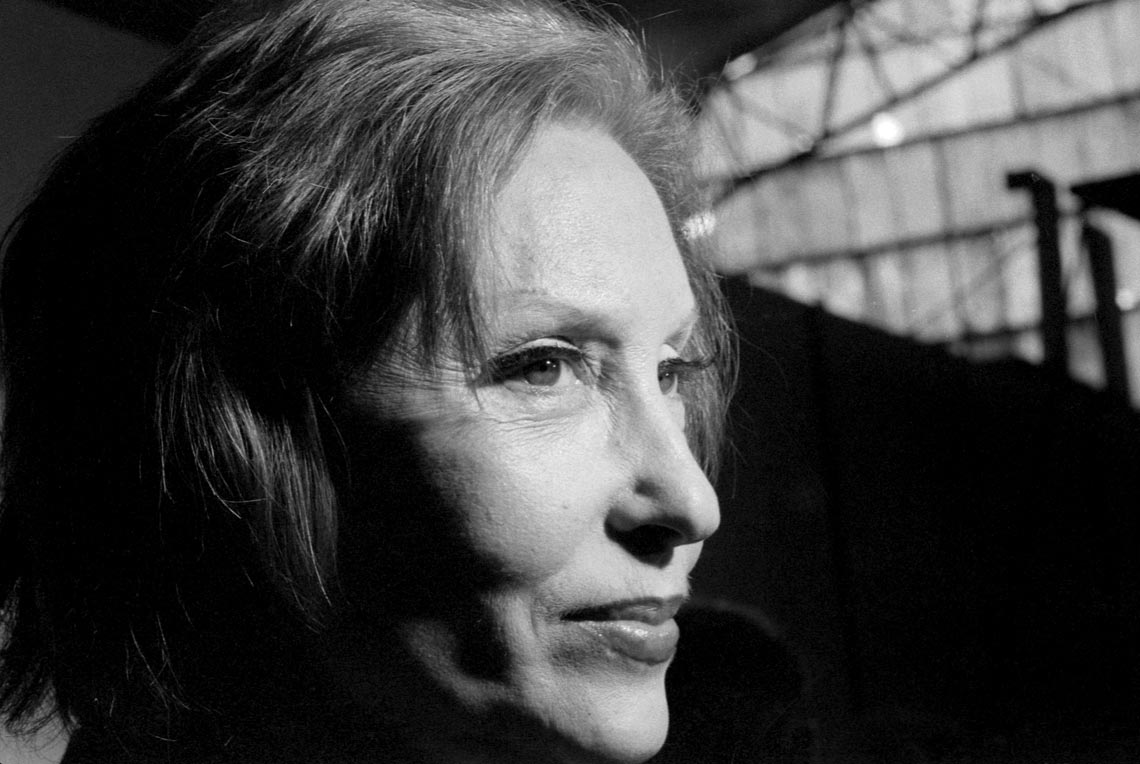

On the eve of Clarice Lispector’s one hundredth birthday, which will officially be celebrated on December 10, a series of events has already begun in her honor. Lispector, (1920–1977) is the author of such classics as The Hour of the Star (A hora da estrela; Livraria José Olympio, 1977) and The Passion According to G.H. (A paixão segundo G.H.; Editora do Autor, 1964). “A lot of people think that Clarice has only gained fame recently, but she’s one of the few Brazilian writers who were recognized in her lifetime—and translated into French during the first half of the 1950s. In 2010 there were 180 translations of her work, worldwide,” says Nádia Battella Gotlib, a retired professor of Brazilian literature at the School of Philosophy, Letters and Languages, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP). “Perhaps a good way to honor her now is to keep quiet and reread her books.”

Born in Ukraine, Lispector arrived in Brazil with her parents and two sisters in 1922, to escape from anti-Semitism and hardship. The family first arrived in Maceió, in the state of Alagoas, where they had relatives. Three years later, they moved to Recife, Pernambuco. “Clarice, whose birth name was Chaya, lived her childhood in poverty,” continues Gotlib, author of the first biography about the writer, Clarice, uma vida que se conta [A life that counts]. Written as a result of her qualifying thesis for professorship, the work was launched by Ática books in 1995 and is currently published under the EDUSP imprint. “Recife is where she learned to read, and fell in love with literature. She even sent some stories to the children’s page of the newspaper Diário de Pernambuco, which were never published, and also wrote a play. It was the beginning of everything.”

After his wife’s death in the 1930s, Pedro Lispector decided to take his daughters to study in Rio de Janeiro. The youngest, Clarice, chose law school. In 1939, she entered the University of Brazil, now known as the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). “She was very concerned about social issues and said she chose the law to try to improve the Brazilian prison system, but never worked in the profession,” says poet Eucanaã Ferraz, from the School of Languages and Literature at UFRJ. During her undergraduate studies she began working as a journalist, which is also when she began to get stories published in magazines. “Clarice was one of the first Brazilian journalists at a time when women were not in the newsrooms,” observes Yudith Rosenbaum, a professor of Brazilian literature at FFLCH-USP, who has studied the author’s work through a psychoanalytic lens since the 1990s.

In 1943, the year Lispector graduated, the publisher A Noite released Near to the Wild Heart, her first novel, which at the time earned the following comment from literary critic Antonio Candido (1918–2017): “An impressive attempt to take our awkward language to little-explored domains, forcing it to adapt to thoughts replete with mystery, wherein we feel that fiction is not an exercise or emotional adventure, but a true instrument of the spirit.” The book, which follows its protagonist Joana, without chronological order, was “splendidly received,” recalls João Camillo Penna, of the School of Languages and Literature at UFRJ, and received favorable reviews, such as those of poet Sérgio Milliet (1898–1966). One of the dissonant voices was Álvaro Lins (1912–1970), at the newspaper Correio da Manhã, who didn’t like the fragmented narrative, which was precisely the aspect that made the work innovative. “In any case, Clarice gained immediate recognition with the book, which already features certain themes that would become recurrent in her work, such as women’s issues and metaphysics,” says Penna.

Clarice Lispector family archive

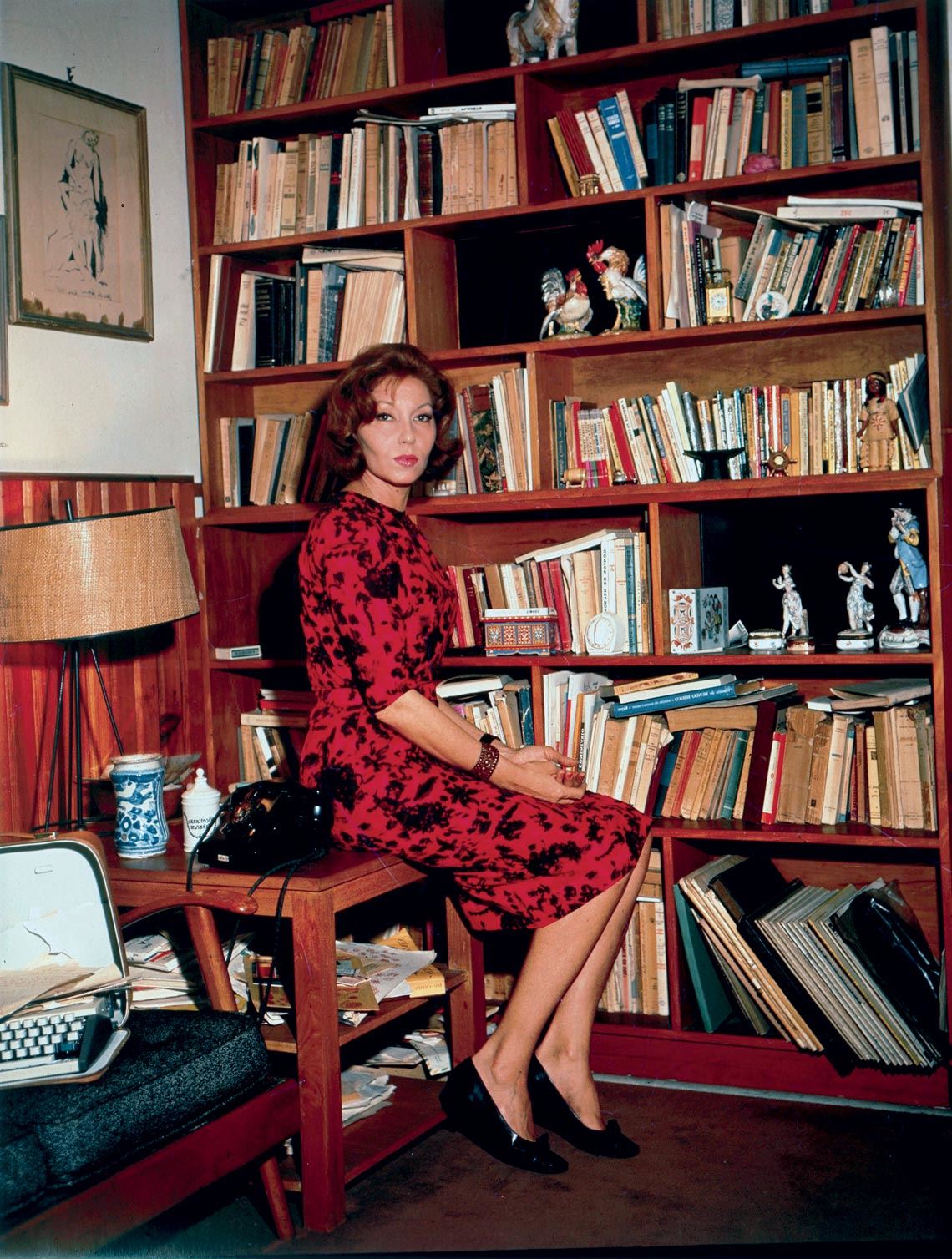

The author of The Passion According to G.H. in her Rio de Janeiro apartment, during the 1960sClarice Lispector family archiveThat same year Lispector married a college classmate, future diplomat Maury Gurgel Valente (1921–1994), with whom she had two children, Pedro and Paulo. As a result of her husband’s profession, she would spend time living in places like England and the United States. In Naples, Italy, she finished her second novel, The Chandelier (O lustre; Agir, 1946), and, later, in Switzerland, “amid the terrifying silence of the streets of Bern,” as she wrote in a letter to her sisters, concluded The Besieged City (A cidade sitiada; A Noite, 1949). The author’s first three books were reissued at the end of last year by the Rocco press, launching the series of publications they have planned for her centennial. “There will be a total of 18 titles, including novels, story collections, and her newspaper and magazine columns,” says editor Pedro Karp Vasquez. “At the end of each volume, we’ll have an afterword written by a Lispector scholar—not as a reading guide, which is something that would Clarice wouldn’t have approved of, but as a tool for expanding the possibilities of interpretation.”

The book jackets, by graphic designer Victor Burton, feature works painted by the writer herself near the end of her life, between 1975 and 1976. “Clarice had no pretensions of being a visual artist; the act of painting was a free form of expression,” says Ricardo Iannace, a professor of Comparative Studies of Portuguese Language Literatures in the postgraduate program at USP, who wrote the book Retratos em Clarice Lispector: Literatura, pintura e fotografia [The portraits of Clarice Lispector: Literature, painting and photography] (Editora UFMG, 2009). Developed from his doctoral thesis, the researcher gathered 22 of the writer’s paintings that were in the collections of Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa and Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), and at the home of one of Lispector’s closest friends, writer Nélida Piñon. “Except for one canvas, the works are done on wood with paint, melted candle, ballpoint pen, and even nail polish. It’s a mixed technique, mainly of an abstract bent, which shares an affinity with her writings.”

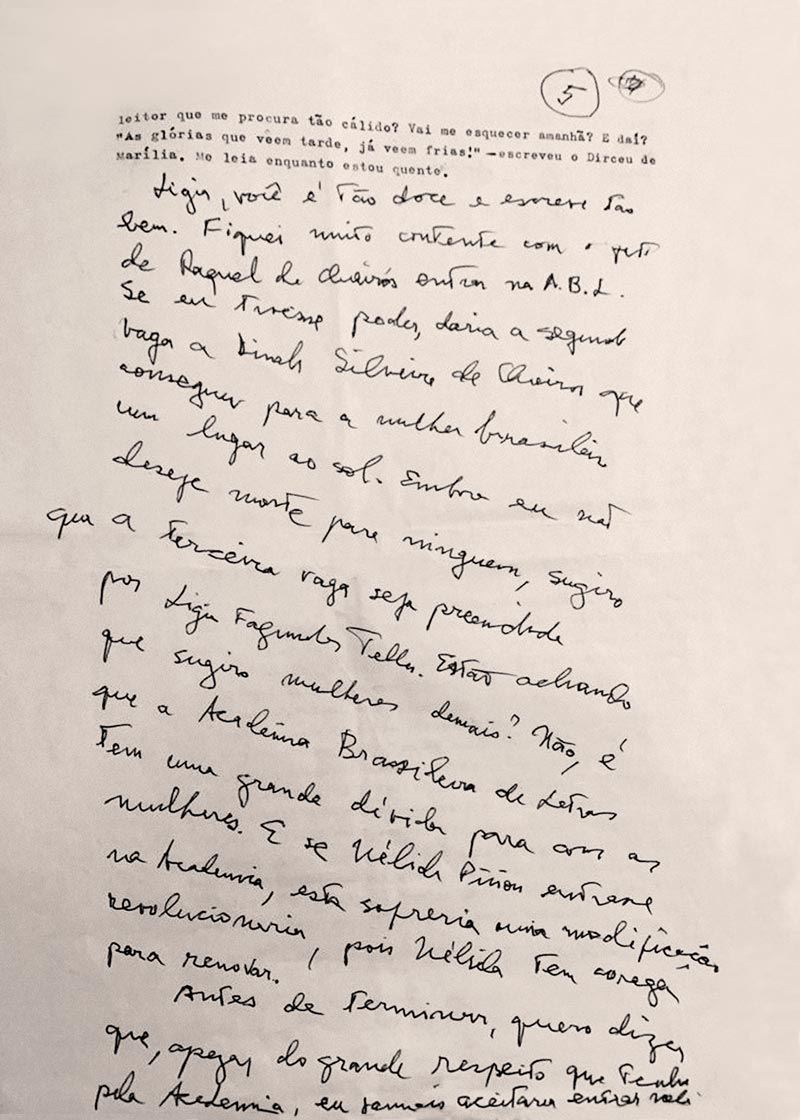

One title researchers had long been waiting for was launched in September. The book Todas as cartas (The complete correspondence) collects 284 letters written by Lispector from the 1940s through the 1970s. “Among her unpublished writings are around 50 letters sent to interlocutors such as Rubem Braga [1913–1990], Otto Lara Resende [1922–1992], Mário de Andrade [1893–1945] and Lygia Fagundes Telles,” points out Teresa Montero, who earned a doctorate in literature at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ) and has been a scholar of Lispector’s work for three decades. “In her correspondence with João Cabral de Melo Neto [1920–1999], for example, she reflects on literary practice and her state of mind when she faced a kind of exile in Bern, where she had accompanied her husband.”

Clarice Lispector family archive

Note sent by Lispector, shortly before her death, to the writer Lygia Fagundes Telles, in November 1977Clarice Lispector family archiveMontero wrote the preface and 510 entries that give context to the collected material. She is also preparing an expanded edition of her 1999 book Eu sou uma pergunta: Uma biografia de Clarice Lispector [I am a question: A biography of Clarice Lispector], to be launched next year. Rocco also plans to publish G.H. – Diário de um filme, the provisional title of a book written and edited by Melina Dalboni, screenwriter of the film A paixão segundo G.H., directed by Luiz Fernando Carvalho. Dalboni explains that the idea was to provide a step by step diary of the film’s production and explore the dialogue between literature and cinema. Before filming began in 2018, part of the filmmaking team attended workshops given by scholars of Lispector’s work, such as Gotlib, Rosenbaum, José Miguel Wisnik, and Franklin Leopoldo e Silva. “They helped us to enter Lispector’s universe, where it’s necessary to read behind the words,” says Dalboni. “Clarice is a writer who creates subtext.”

The feature film, which hasn’t yet set a premiere date, was inspired by the Lispector novel of the same name. Actress Maria Fernanda Cândido plays an upper-middle-class sculptor who, when visiting the room of Janair, a dismissed maid, goes through an existential experience so profound she eats a cockroach. “It’s an uncomfortably contemporary story with a devastating revolutionary power that’s most typically read through a philosophical and psychological lens, masking the novel’s innumerable structural layers, such as class struggle and racial prejudice,” observes Carvalho.

“In the book, G.H.’s dawning awareness happens with an abrupt, heavy impact,” says researcher Ludmilla Carvalho Fonseca, whose doctoral thesis compared this awakening to a similar process in Les Belles Images, published in 1966 by French writer Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986). In her thesis, defended in July at the College of Letters and Sciences of the Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Assis campus, Fonseca seeks to understand how the two protagonists of these novels, both written during the 1960s, changed the ways they thought about the social conditions they found themselves enmeshed in, and about the existential condition of women.

Another film under production is O livro dos prazeres. The film is loosely inspired by An Apprenticeship, or The Book of Pleasures, a Lispector novel that was first published by Sabiá in 1969, and portrays the love story between a philosopher, Ulisses, played by Javier Drolas, and an anguished teacher, Lóri, portrayed by Simone Spoladore. “The plot has been adapted for today’s audiences, and deals with Lóri’s intimate journey of self-discovery, and her conflict with her own emotions and self-realization in a society that’s still patriarchal, even 50 years after the book was launched. Lóri learns to love through confronting her own loneliness,” in the analysis of Marcela Lordy, director of the feature film, which is scheduled to premiere next year. “The book was written after AI-5, [a repressive governmental decree], at the height of the military dictatorship [1964–1985], the setting when Lóri takes control over her own life. Clarice promotes an internalized feminist revolution.”

The filmmaker will discuss the film on a panel with psychoanalyst Maria Lúcia Homemat at the International Colloquium: One Hundred Years of Clarice Lispector, organized by Yudith Rosenbaum and professor Cleusa Rios Passos, also from FFLCH-USP. Scheduled for October 19–21, the event will take place online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It will have the participation of scholars from Brazil, Portugal, the United States, and France, which Rosenbaum believes reflects the growing worldwide reach of Lispector’s writing. “A work’s endurance depends not only on the excellence of the author, but also on the various readings that come out of it,” says the author of Metamorfoses do mal: Uma leitura de Clarice Lispector (Metamorphoses of evil: A reading of Clarice Lispector) (EDUSP/FAPESP, 1999). “And today Clarice has them to spare. The result is that the work emerges renewed with each reading.”

A variety of readings generated by Lispector’s works are also exemplified in the book Visões de Clarice Lispector: Ensaios, entrevistas e leituras (Visions of Clarice Lispector: Essays, interviews, and readings), launched this year by the Federal University of Ceará (UFC) University Press. Organized by Fernanda Coutinho and Sávio Alencar, the publication brings together works by 24 scholars reflecting on the writer’s legacy, including translators of her work into Italian, German, Spanish, and Yiddish. “Clarice was in a constant state of inquiry and her writing, with its restless and disturbing character, was able to say the unspeakable when dealing with themes such as the feminine, and animality,” says Coutinho, from the Graduate Program in Literature at UFC. “I think that’s why it’s so contemporary, and continues to seduce new generations of readers.”

In 1959, Lispector separated from her husband and returned to Rio de Janeiro with her two young children, after 16 years away from Brazil. To support herself she returned to publishing short stories, this time in the magazine Senhor, and published the book Family Ties (Laços de família; Livraria Francisco Alves Editora, 1960), which brought her once again into the heart of Rio literary society. “In addition, writing short stories exposed her to a wider audience,” observes Penna, from UFRJ. That public grew even larger when Lispector began to write a column for Jornal do Brasil in 1967. Part of this writing was collected in the book A descoberta do mundo (The discovery of the world) (Nova Fronteira, 1984), edited by her youngest son, economist and writer Paulo Gurgel Valente.

In the play Ao redor da mesa, com Clarice Lispector (Around the table, with Clarice Lispector), written and directed by Clarisse Fukelman, the approximately 40-year-old Lispector, of the period when she returned to Brazil, encounters her almost sixty-year-old self. Fukelman, a professor at the School of Communication at PUC-RJ, and a specialist in Lispector’s work, originally staged the play at Espaço SESC in Rio de Janeiro in March, but it had to be closed due to the pandemic. Converted into a series of nine episodes with the updated title Ao redor da tela, com Clarice Lispector (Around the screen, with Clarice Lispector), the performance is available during the month of October on the SESC RJ YouTube Channel.

The pandemic also affected the exhibition Constelação Clarice (Constellation Clarice) at the IMS, which holds a portion of the writer’s collected works. Scheduled to open in December, the show is slated to open in July next year, in São Paulo. “The idea is to put together not only biographical material from the honoree, but also works by Lispector’s contemporaries in the visual artists, such as Djanira [1914–1979], Fayga Ostrower [1920–2001], and Maria Bonomi,” explains Eucanaã Ferraz, the show’s curator, together with writer Verônica Stigger, who also organized the Institute’s Clarice Lispector website. “We are attempting to discover what troubled these women at a time that was still marked by feminine submission, and thus establish the ties between them.”

Project

Fragments of passion and beauty: Growing awareness in The Passion According to G.H. (1964), by Clarice Lispector, and Les Belles Images (1966), by Simone de Beauvoir (no. 16/13683-7); Grant Mechanism Doctoral (PhD) Fellowship; Supervisor Daniela Mantarro Callipo (USP); Beneficiary Ludmilla Carvalho Fonseca; Investment R$152,405.89.