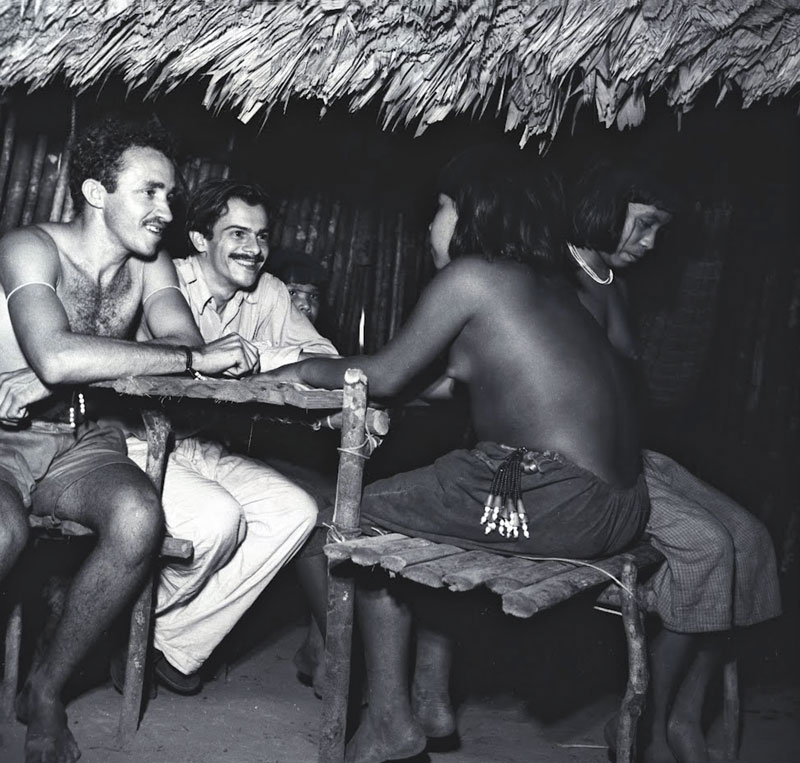

Archive of the National Indigenous Peoples MuseumFrom left: João Carvalho and Darcy Ribeiro talk to a Kaapor girl in 1951Archive of the National Indigenous Peoples Museum

When he was commissioned in 1947 by the Indian Protection Service (SPI), as it was then known, for two expeditions to the Kaapor reservations on the border of Pará and Maranhão States, anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro (1922–1997) realized that although he knew a little of their language, he would need an interpreter to better understand aspects such as ancestry and rituals. It was specialist Indigenous interpreter João Carvalho who assisted with the task. “João is our interpreter, and his role is equally important during both social and working receptions, so he has to talk a lot to make up for my silence,” wrote Ribeiro in his accounts of the expedition collated into Diários índios: Os Urubu-Kaapor (Indian diaries: The Urubu-Kapoor) (Companhia das Letras, 1996).

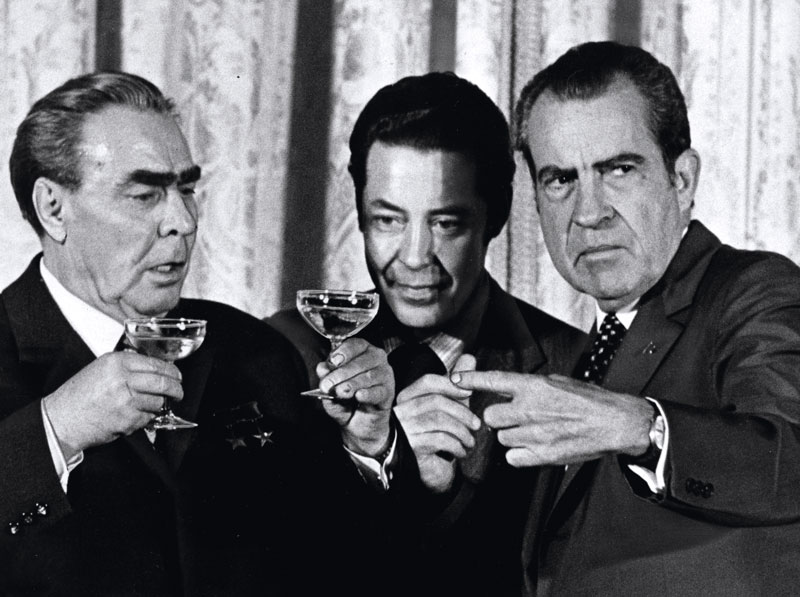

Their partnership is recorded in the book Fotografias de intérpretes: Em busca das vidas perdidas (Photographs of Interpreters: In Search of Lost Lives), by British translator John Milton, a professor at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP). Published in Brazil by Lexikos in 2022, the English version of this collection was released at the end of 2024 by the UK’s Cambridge Scholars Publishing. In the work, the researcher brings together stories from interpreters around the world, for example Viktor Sukhodrev (1932–2014), who worked in Soviet diplomacy during the Cold War (1947–1991). According to the book, US president Richard Nixon (1913–1994) trusted Sukhodrev more than his own team, given that the interpreter was distanced from White House power struggles.

One chapter is dedicated to Indigenous interpreters in Brazil, such as Megaron Txucarramãe, translator and interpreter for her uncle Raoni Metuktire, chief of the Caiapó people and one of the country’s foremost Indigenous leaders. Megaron, who directed the Xingu Indigenous Park from 1985 to 1989, does not do literal translations—she includes explanations and adds remarks. “As an Indigenous leader herself, her presence is not just semantic in value, but also symbolic,” says Milton.

Interpreters work with oral language in an instantaneous, simultaneous manner at events of all kinds, from scientific conferences to political meetings. “Generally speaking, translators have more time to edit and reflect upon a certain piece of written material. But the role of both is to be a bridge between different cultures,” explains Milton. “In literary terms, much is said about writers, but little attention is paid to the work of translators. I think it’s important to bring these careers out from the sidelines, as they can help to throw light on aspects of history and literary work, for example.”

Bob Burchette / The Washington Post via Getty ImagesSukhodrev between Soviet leader Leonid Brejnev (left) and US President Richard Nixon in the 1970sBob Burchette / The Washington Post via Getty Images

Commenced in 2017, the collection Palavra do tradutor (Translator’s word) has this aim. “Our idea is to disseminate the work of translators active in Brazil and overseas linguists who translate Brazilian literature,” says Dirce Waltrick do Amarante, of the Translation Studies Graduate Course at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), who is heading up the initiative alongside other professors from the same institution. The project has now published eleven books, featuring interviews with and biographical data of translators across a range of genres such as fiction, poetry, and theater. The first two volumes were published by Medusa in 2018. One is dedicated to Aurora Fornoni Bernardini, of the USP Oriental Letters Department, known for her translations from Italian and Russian into Portuguese. The other features Donaldo Schüler, a retired language and Greek literature professor from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). All these works can be downloaded free of charge on the UFSC website.

According to translator Luciana Carvalho Fonseca, a professor at the FFLCH-USP Modern Letters Department, contemporaneous translation theory studies were largely based on the notion of equivalence, one of whose exponents in the 1960s being US linguist Eugene A. Nida (1914–2011), who applied it to his translation of the Bible. “In this concept, the task of translation is seen as the transposition of text in one language to another, with much reverence for the original work,” says the researcher. Other proposals emerged over time, adds Fonseca, for example functionalism, which allows adaptations—cuts, insertions, footnotes, and introductory texts. There is also the paradigm of descriptive translation studies, which conceive the translated text based on aspects such as the sociohistorical background, the reception, circulation, and personality of translators.

Translators and interpreters intermediate different cultures

In recent years, Fonseca has been poring over the career of Maria Velluti (1827–1891), a Portuguese-born translator, actress, and director, who migrated to Brazil in 1847. The story began after an informal conversation between Fonseca and researcher Dennys Silva-Reis, of the Federal University of Acre (UFAC), on the erasure of women from Brazilian translation history. The pair came up with almost sixty translators’ names from the digital periodicals section of the Brazilian National Library in Rio de Janeiro, and wrote the article “Nineteenth century women translators in Brazil: From the novel to historiographical narrative” (2018). Velluti was among these names. “She was often cited by journals, translating more than 40 works, and introduced the French realism theater to Brazilian companies of the period. This caught my attention, and I wanted to find out more about her career,” says Fonseca. During her work, the researcher found critiques in the press of the time, some written by Machado de Assis (1839–1908), with praise for Velluti’s work.

“One of the biggest challenges for those researching this field is finding archives and collections documenting the contributions made by these professionals, from behind the scenes at publishing houses to correspondence and manuscripts,” says Bruno Gomide, professor of Russian culture and literature at USP, who coordinates a FAPESP-funded research project looking into the translators of Russian texts in Brazil. One line of this work looks at the output and life of Boris Schnaiderman (1917–2016), born in Ukraine; Tatiana Belinky (1919–2013) and Valeri Pereléchin (1913–1992), both from Russia; and Hungarian Paulo Rónai (1907–1992). “All of them made their home in Brazil. Belinky and Schnaiderman both arrived during their childhood in the 1920s, while Rónai and Pereléchin came later: in the 1940s and 1950s respectively,” says the researcher, who organized the seminar Translators’ Stories, held at USP’s Centro MariAntonia in the São Paulo State capital in August 2024.

Victor Moriyama / Folhapress | Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPTatiana Belinky and Boris Schnaiderman translated works by Russian authors into PortugueseVictor Moriyama / Folhapress | Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

At the event, Gomide talked about Schnaiderman, famous for the rigor with which he translated short stories, novels, and poems directly from Russian to Portuguese, starting in the 1940s (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 236). “He was one of the first to have a continuous, systematic, and professional career in Russian literary translation not just in Brazil, but in Latin America as a whole,” says the researcher. He also shone on the institutional stage, contributing to formulation of the Russian language course at USP in 1961. “Schnaiderman translated not only literary classics to Portuguese, but also works by Russian theorists with innovative proposals across a range of areas, for example linguist Mikhail Bakhtin [1895–1975],” says Walter Carlos Costa, of UFSC and the Graduate Program in Translation Studies at the Federal University of Ceará (UFC). “He also had significant contact with Brazilian writers: he exchanged correspondence with Dalton Trevisan [1925–2024] and was a friend of Rubem Fonseca [1925–2020],” adds the researcher, who is currently exploring Schnaiderman’s contributions to the Literary Supplement of newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo.

Rónai was persecuted by the Nazis and spent six months in a forced labor camp in Hungary during the Second World War, before moving to Brazil in 1941 at the invitation of the Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) government. “He began studying Portuguese solo in 1937, and around two years later published Mensagem do Brasil (Message from Brazil), an anthology of Brazilian poems translated into Hungarian, with a preface by the Brazilian ambassador in Hungary,” says independent researcher Zsuzsanna Spiry, who defended her doctoral thesis on the intellectual at FFLCH-USP in 2016. “Rónai arrived in Brazil in March 1941, and in June of the same year he gave a talk at the Brazilian Academy of Letters.”

According to the researcher, the translator participated actively in Brazilian intellectual life. “Among other output, he wrote literary critique articles for key newspapers in the country and worked as an editor, including on books by Guimarães Rosa [1908–1967], with whom he was very close,” says Spiry, coordinator of the book Rosa & Rónai: O universo de Guimarães por Paulo Rónai, seu maior decifrador (Rosa & Rónai: The world of Guimarães by Paulo Rónai, his greatest decoder (Bazar do Tempo, 2020), jointly with journalist and editor Ana Cecilia Impellizieri Martins. One of Rónai’s most meaningful works was the arrangement of Mar de histórias: Antologia do conto mundial (Sea of histories: Anthology of the worldwide tale) (Editora Nova Fronteira), with philologist Aurélio Buarque de Holanda (1910–1989). Some of the texts in this ten-volume compendium, commencing in 1945 and concluding in 1990, were translated by the pair. “Rónai did not only master Russian, but a further eight languages including Latin, French, and German,” says Spiry.

Spiry sees another noteworthy part of Ronai’s canon in the essays and reflections on translation practice, collated under titles such as Escola de tradutores (School of translators) (Ministry of Education and Health Documentation Service, 1952) and Tradução vivida (Translation lived) (Editora Nova Fronteira, 1974). Amarante, of UFSC, agrees. “A lot of his texts anticipated debates on core aspects of translation theories in modern times, such as foreignization and machine translation [using computer programs],” she says.

Fernando Rabelo / FolhapressHungarian translator Paulo Rónai arrived in Brazil in the 1940sFernando Rabelo / Folhapress

Belinky became known as an author of children’s books and for her adaptation of Monteiro Lobato’s O sítio do pica-pau amarelo (The Yellow Woodpecker Farm) for the TV Tupi series broadcast between 1952 and 1963. “But she also translated a number of Russian literature books into Portuguese, including works for children and by classical and contemporary authors for adults,” says Cecilia Rosas, a member of the research group Exílio e Tradução (Exile and Translation), coordinated by Gomide at USP. This is the case of No degrau de ouro (On the Golden Porch) (1987), by Tatiana Tolstáia, published in Brazil in 1990 by Companhia das Letras, and reprinted last year by Editora 34.

Of the four, Pereléchin is the lesser-known name among the Brazilian public. A translator, poet, and critic, he lived for four decades in Brazil. “He was fluent in English, Mandarin, and Portuguese,” says Gomide. With a turbulent life history, Pereléchin wrote homoerotic poetry, but also made anti-Semitic comments and praised the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964–1985). He died poor and blind in Retiro dos Artistas (Artists’ Retreat), Rio de Janeiro.

According to Gomide, one of the research aims is to find converging points in the careers of the four translators. Between the 1960s and 1980s, for example, Rónai and Schnaiderman exchanged correspondence and shared observations on translation work. Additionally, the former sat on Schnaiderman’s habilitation thesis panel in 1974 at USP, published in 1982 by Perspectiva under the title Dostoiévski: Prosa e poesia. (Dostoevsky: Prose and poetry). “Over the course of their lives, they agreed and disagreed at different moments,” concludes Gomide.

The story above was published with the title “Lives translated” in issue 347 of january/2025.

Project

Exile and translation in Brazil: Russian texts (nº 22/05910-4); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Bruno Barretto Gomide (USP); Investment R$355,408.64.

Scientific articles

FONSECA, L. C. & SILVA-REIS, D. Maria Velluti’s theater translations in nineteenth-century Brazil: A mise-en-scène. Revista da Associação Brasileira de Literatura Comparada. no. 34, pp. 23–46. 2018.

FONSECA, L. C. Mulheres de imaginação ardente e leitores terríveis: Maria Velluti, uma traductora do século XIX. Boletim 3×22. pp. 108–17. 2021.

GOMIDE, B. B. Le texte littéraire russe et l’émigration: Les trajectoires parallèles de Schostakovsky et Schnaiderman. Brésil (s) – Sciences Humaines et Sociales. Vol. 22, pp. 1–20. 2022.

Book

MILTON, J. Fotografias de intérpretes: Em busca das vidas perdidas. São Paulo: Lexikos Editora, 2022.

Book chapter

GOMIDE, B. B. Translation Russian literature in Brazil: Politics, emigration, university and journalism (1930–1974). In: MAGUIRE, M. & McATEER, C. Translating Russian literature in the global context. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Open Book Publishers, 2024.