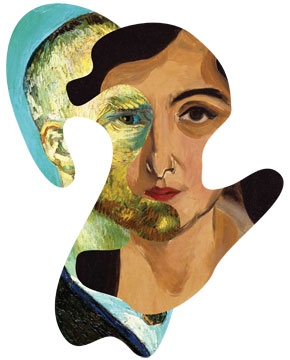

Laura Daviña | Collage based on a Self-portrait, by Van Gogh, and Lorette, by Matisse — Maria, do you want to be a woman or a man?

Laura Daviña | Collage based on a Self-portrait, by Van Gogh, and Lorette, by Matisse — Maria, do you want to be a woman or a man?

In asking this question, Dr Berenice Mendonça Bilharinho was seeking important information to plan the treatment of Maria, then 16, who was wearing a flowered dress on that day. Berenice had noticed that Maria looked fixedly at the ground so that her long hair would cover her bearded face. Her levels of the main male hormone, testosterone, were normal for a man. Her genitals were both male and female, predominantly masculine. Facing the doctor, in a room at the Clínicas hospital (HC) in São Paulo, Maria replied evasively, in a deep voice with a thick accent from the inner state of Minas Gerais:

— Oh, it’s up to you, ma’am.

Berenice says that she did not know what to do. She could not choose for Maria. As it seemed clear that Maria did not feel right as a woman, she called the team that worked with her – Walter Bloise, Dorina Epps and Ivo Arnhold. Together, they decided to do what was not in the treatment manuals for people with sexual development disorders. They suggested that Maria live in São Paulo for a year as a man to see which sex she adapted better to socially.

Maria put on men’s clothes for the first time and got another name: João, say. She left the hospital with her haircut and worked in a job that the social worker arranged for her. Maria liked being João. AT HC, which has been since that time a national benchmark in this field, Maria underwent surgery that corrected the ambiguity of her genitals, making them masculine. When Maria was born, the midwife had commented that babies like that died soon, but João is now 50 years old and, according to the latest news, lives happily in inner-state Minas Gerais.

João has always been male, from a genetic point of view. Like all men, his cells contain an X chromosome and a Y chromosome (women have two X chromosomes) plus 23 pairs of chromosomes unrelated to sex. Because of a flaw in a gene in a non-sexual chromosome, however, his body produces very low levels of 5-alpha reductase type 2, an enzyme. As a result, his male genitals had not developed fully and had a feminine appearance, which caused him to be registered as a woman.

His problem – now under control, although his cells continue to have this disorder – illustrates one of 23 types of sexual development disorders (SDD) whose possible origins, evolution, signs and treatments Berenice, Arnhold, Elaine Maria Frade Costa and Sorahia Domenici presented at the end of 2009 in an article published in the journal Clinical Endocrinology. By bringing together the group’s 30 years of experience with the experience of others in Brazil and abroad, this work shows how genetic defects can cause metabolic deviations that expand or reduce the production of male hormones and induce the formation of male and female sexual organs, either partial or complete, in the same individual.

The stories that accompany the diagnosis usually come loaded with anguish from parents who say they never knew for sure if the baby they had was a boy or girl. Berenice reminds us that to know the sex of a newborn is important not only in order to answer one of the first questions parents hear after the child is born. It is also essential for deciding what name to give the baby and how to treat the child, as many adjectives and nouns in Portuguese have gender (masculine or feminine), all of which come together to define the psychological identity of children.

She said stories of rejection usually accompany children with ambiguous genitalia, who were previously denominated pejoratively as hermaphrodites, or pseudo-hermaphrodites. The presence of male and female genitalia leads many girls to be registered and to live as boys – and many boys to live as girls. Confusing the gender of newborns with ambiguous genitalia is easy, because “the genitals are often not properly examined at birth and girls, especially the premature ones, often have a seemingly hypertrophied clitoris,” she says.

Laura Daviña | Collage based on self portrait by Rembrandt and Retrato de Baby de Almeida, by Lasar Segall Genes located in sex chromosomes (X and Y) or any of the other 23 pairs of chromosomes of a normal human cell may be defective – or have mutations – and cause one of 23 types of DSD. These disorders represent a wide group of different problems, warned Martine Cools, from the University of Gent, Belgium, and three researchers from the Netherlands in a May 2009 study in the World Journal of Pediatrics. The same genetic defects may cause various different symptoms and signs and, moreover, a similar clinical picture may result from different genes. In just one gene, SRY, which operates only in the early days of intrauterine life, there can be 53 alterations that harm sexual development. Other mutations can reduce or increase the production of sex steroid hormones, the most important of which is testosterone, or compounds such as cholesterol, a precursor of these hormones.

Laura Daviña | Collage based on self portrait by Rembrandt and Retrato de Baby de Almeida, by Lasar Segall Genes located in sex chromosomes (X and Y) or any of the other 23 pairs of chromosomes of a normal human cell may be defective – or have mutations – and cause one of 23 types of DSD. These disorders represent a wide group of different problems, warned Martine Cools, from the University of Gent, Belgium, and three researchers from the Netherlands in a May 2009 study in the World Journal of Pediatrics. The same genetic defects may cause various different symptoms and signs and, moreover, a similar clinical picture may result from different genes. In just one gene, SRY, which operates only in the early days of intrauterine life, there can be 53 alterations that harm sexual development. Other mutations can reduce or increase the production of sex steroid hormones, the most important of which is testosterone, or compounds such as cholesterol, a precursor of these hormones.

In a 2004 study, the USP group presented 14 mutations in eight genes that prevent the production of hormones related to sexual development. Dr. Ana Claudia Latronico, who led this work, linked each mutation to its external manifestations, based on the examination of nearly 400 children, teenagers and adults from across the country and from neighboring countries that were treated at USP.

Under the coordination of Tânia Bachega and Guiomar Madureira, the team identified 18 mutations – at least four of which are specific to the Brazilian population – which may lead to the most common disorder of sexual development: virilizing congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which is characterized by excessive development of the clitoris, to the point where it resembles a penis.

Sexual development disorder results from mutations in the CYP21A2 gene in chromosome 21 (not sexual), which reduce the production of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase. Consequently, the adrenals produce less of one hormone, cortisol, and more of another, testosterone, than they should. The girls suffer from genital virilization in the womb. They are born with a hypertrophied clitoris and a scrotum without testes covering the vagina, and are sometimes registered as boys when the defect is not identified at birth. Because of changes in this same gene, boys may have a form of hyperplasia that does not result in sexual ambiguity, but could cause a severe loss of salt; enough to cause brain damage or death from dehydration if not treated in time.

It is estimated that one in every 15 thousand people has this form of hyperplasia, according to studies conducted in Europe and North America. Surveys in Brazil are rare. “The geneticist Elizabeth Silveira, co-supervised by Tânia Bachega, examined blood samples collected from infants in the state of Goiás, which carries out routine screening tests to detect 21-hydroxylase deficiency, and concluded that the yearly incidence of hyperplasia in Brazil is one case per 10 thousand live births,” says Berenice. At least 840 cases, therefore, should have been diagnosed at the universities of São Paulo and other states. The Clínicas hospital at the University of São Paulo, which should have received the highest number of cases, recorded only 380.

“Parents tend to hide or deny the existence of their children’s’ sexual development disorders, because facing the facts can be emotionally painful. Most patients with sexual development disorders only get here as teenagers or adults,” says Berenice. In an extreme case, less than one year ago, she met a 70-year-old woman who had sexual ambiguity and only sought help after her mother, who would not let her talk about it, had died.

“It is best to diagnose and treat sexual ambiguity as soon as possible, preferably before the age of 2, when children have not yet grasped the concepts of sex and gender,” says psychologist Marlene Inácio, who has worked with patients with sexual ambiguity at the HCfor 28 years. Initially, she says, the diagnosis on which the treatment was based could take from six months to a year. “Nowadays, the results of laboratory tests come out in a week,” she says.

In her doctoral thesis, Marlene analyzed the reports of 151 people with sexual ambiguity who were treated at the HC, of whom 96 were genetically male (XY) and 55 genetically female (XX), aged 18 to 53. Her objective, by means of a 121-item questionnaire, was to see how these people had lived during their childhood, adolescence and adult life, before having been diagnosed and treated, if they had managed to adapt from a psychiatric, social and sexual point of view with the sex they adopted.

Marlene concludes that, broadly speaking, they are doing well. Many have married or intend to marry. The men with sexual ambiguity are sterile, because their seminal fluid is infertile or because of the corrective surgery. However, two have had children through in-vitro fertilization using their semen. Of a group of 20 women with one of the forms of sexual development disorder (46,XY), 18 have changed sex and are now men.

This is the case of another Maria, who came from inner-state Bahia about three years ago. She had a man’s thick voice, wide shoulders and strong arms from ploughing the fields. She had lived until the age of 16 isolated in a room in the back of her house, with little contact with her family, and did not know how to read or write. “Psychologically, she was a man, and preferred to be a man because she needed the strength to oppose the parents who had made her live as a woman,” says Marlene. “She had a large clitoris, which, according to her, gave her sexual pleasure. She wanted to be a mechanic.”

In another survey, Maria Helena Palma Sircili, one of the doctors in the group, found that 90% of the 65 people with karyotype 46,XY (those who are genetically male but socially female) operated on from 1964 to 2008 in the urology department of the HC-USP were satisfied with the sex they had chosen and had adjusted to the change. 69% of those who had chosen the male sex and 29% of those who had chosen the female sex were married. This study, to be published in the Journal of Urology, included a finding that surprised the researchers themselves: patients’ satisfaction with their sexual activity did not depend on the size of their penis.

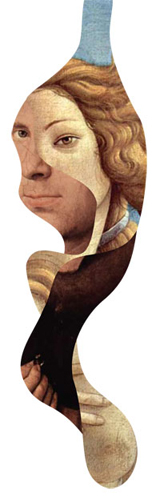

Laura Daviña | Collage based on Portrait of Jan de Leew, by van Eyck, and The Birth of Venus, by Botticelli.Men who have sexual ambiguity may not have genitals as developed as those of other men, but they do not complain. “This was surprising, because urologists say that men, even those without biological sexual disorders, frequently complain about the size of their penises,” says Berenice. Marlene attributed this finding to a greater satisfaction with a male identity than with the dimensions of the penis: “Our psychological counseling service suggests that patients explore other forms of sexual satisfaction, exploring their entire bodies, and not only the genitals.”

Laura Daviña | Collage based on Portrait of Jan de Leew, by van Eyck, and The Birth of Venus, by Botticelli.Men who have sexual ambiguity may not have genitals as developed as those of other men, but they do not complain. “This was surprising, because urologists say that men, even those without biological sexual disorders, frequently complain about the size of their penises,” says Berenice. Marlene attributed this finding to a greater satisfaction with a male identity than with the dimensions of the penis: “Our psychological counseling service suggests that patients explore other forms of sexual satisfaction, exploring their entire bodies, and not only the genitals.”

These results make Berenice and her keen to work on new projects. One was planned and is currently being coordinated by Elaine: research on a small freshwater fish, the paulistinha, also known as the zebrafish or Danio rerio, with which they intend to examine the appearance of sexual development disorders. Another situation was unexpected: at a congress held last year in the United States, Berenice was invited to participate in a five-person panel to advise the International Olympic Committee. They had to help solve a difficult problem: can a female runner with sexual ambiguity compete among women? The conclusion was that she can “if the runner is under treatment, with normal testosterone levels for women,” says Berenice. Another proposal put forth by the doctors for the Olympic committee: “We shouldn’t stop people with ambiguous genitalia from participating in any sport.”

These studies illustrate a work style that values the choice of parents of children with sexual ambiguity or those of adults with sexual ambiguity themselves. Listening to parents implies recognizing the frustrations caused by stillborn children or by girls born to parents who wanted a boy. “Before the child is born, the mother imagines what the baby is going to be like; he exists first and foremost in her mind,” says the psychoanalyst Norma Lottenberg Semer, a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo and associate member of the Brazilian Psychoanalysis Society of São Paulo. “What children will be, in sexual and psychic terms, partly reflects the fantasies, the feelings and the thoughts of their parents.”

“The treatment procedures are established by consensus between parents and the multidisciplinary team,” says Berenice. Endocrinologists, surgeons, general practitioners, biologists, psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers are all involved in the diagnosis. “When there is no consensus between the medical advice and the parents’ wishes, the parents’ wishes must be respected.”

Once her team treated a baby girl, now aged 11, who had congenital adrenal hyperplasia, resulting in a clitoris similar to a penis. She had been registered as a boy. According to Marlene, the parents decided that she would be a man and did not accept the recommendation to change to the female sex because they already had two girls and wanted a boy. There was another reason for the choice: “The mother believed that being a woman was a synonym for suffering and living with the shame, as her husband put it, of having had an abnormal child,” says Marlene. Doctors surgically removed Maria’s ovaries and uterus. She will have to take male hormones her entire life, as her body does not produce them.

When they are adult, they themselves choose what sex they want to keep. That was the case of another Maria, who had a deficiency in the 5-alfa-reductase-2 enzyme and appeared with a colored scarf covering her short hair, a men’s shirt buttoned up to her neck and a padded bra. Maria had fallen in love with another employee in the house where she worked as a maid. In the hospital, Maria dressed as a man and liked it. She also adopted another name, Moacir. “We saw this transformation immediately; it was beautiful,” says Marlene. “Moacir’s social sex had been feminine, but his psychological one was masculine.” According to Marlene, Moacir is happily married.

The diagnosis for sexual ambiguity includes seven items. Some are biological, such as hormone levels and external and internal genital structures. Others are subjective, such as the social sex – how one is seen by other people – and gender identity – whether the person sees himself or herself as male or female. “Gender identity is to be and at the same time to feel male or female,” says Marlene. People who just feel that they belong to the opposite sex, without any biological disorder, may have a gender identity disorder.

One of these, transsexualism, occurs when biologically normal people have the conviction that they belong to the opposite sex and do not accept their own sex. “Transsexualism is not connected with genetic issues,” says Norma. “It is more of an identity issue than a sexual one.” This is the case of men who say they are women in men’s bodies. In 2005, the most famous Brazilian transsexual, Roberta Close, having undergone several operations to become female, was granted the right to have another birth certificate printed, changing her name from Luís Roberto Gambine Moreira to Roberta Gambine Moreira and her sex from male to female.

Homosexuality is another separate world from biological disorders. In this case, gender identity is maintained: these are men or women who accept their male or female sex but are attracted to people of the same sex. In transvestites, sexual identity is stable, but gender identity fluctuates: transvestites know they are men, but sometimes behave as women.

At the USP hospital, sexual ambiguity can only be treated after diagnosis and sex choice. This is done by surgically correcting the external male or female genitalia, followed by hormone therapy. “We not only want to treat and solve, but also to understand the causes of a problem. We examine the data and each patient’s personal history, putting together a hypothesis and then ordering tests,” says Berenice. “There is no point in ordering more and more tests without a hypothesis to investigate. We only investigate the genes that are possibly involved in a problem after we have looked at the hormonal diagnosis. Without that, the tests are expensive and ineffective.” She says that she wants to train not just doctors, but medical researchers.

This parallels her own background. Berenice arrived at the Hospital for State Civil Servants in 1972 during her sixth year in medical school. Until then she had been studying at the Federal University of Triangulo Mineiro in Uberaba, state of Minas Gerais. She returned one year later for a residency at USP’s Clínicas hospital, where she met Walter Bloise, who at the time took care of what were then called “intersex” cases.

“I learned a lot more than medicine with Dr. Bloise,” she reminisces. “I learned that we need to treat these problems in a calm and straightforward manner, as if they were a heart disease or a cleft lip.”

At the time, the hormone measurement tests were carried out by the doctors’ own clinics, when possible, as there was no endocrinology laboratory at the hospital. One day Antonio Barros de Ulhoa Cintra, the former head of endocrinology, who had previously been the president of USP and president of FAPESP, asked for a patient’s hormone measurements. She answered:

— As you know, Sir, we don’t measure hormone levels here at the hospital.

— In my day, I had a test-tube with a patients’ blood in my pocket to measure calcium levels.

— Nowadays, just counting the hormones, there are 30. We need a lab, Dr. Cintra.

Emílio Matar, another professor, learned of the conversation and decided in favor of buying the hormone measurement equipment. Bloise encouraged her: “Why don’t you put together a laboratory?” She did, collaborating with Professor Wilian Nicolau. Today, the laboratory’s 80 employees and the researchers from her team are responsible for measuring 60 hormones for the entire hospital. Now she intends to increase on-line discussion of suspected DSD cases with other doctors from around the country, especially pediatricians, so that people with development disorders can be promptly identified and treated.

Another battle ahead, for her and her entire team, is the implementation of the diagnosis of 21-hidroxilase (the enzyme that causes virilizing congenital adrenal hyperplasia) alterations in newborn babies in the state of São Paulo. “It’s a test that costs just R$5 and can prevent diagnostic errors and mortality, especially among the boys, who are born with normal male genitals and so are not diagnosed.”

The Project

Molecular diagnosis of disorders of sexual differentiation (nº 97/01196-1); Type Thematic Project; Coordinator Berenice Bilharinho Mendonça – USP; Investment R$608,743.81

Scientific article

MENDONÇA, B.B. et al. 46,XY disorders of sex development (DSD). Clinical Endocrinology. 2009, 70(2):173-87.