In November 2017, geologist Bernardo Freitas, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and biologist Luana Morais, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of São Paulo (USP) at the time, returned from an expedition to Bonito, in Mato Grosso do Sul, with their backpacks full of rocks collected from a mining area. Months later, examining slices under the microscope taken from these rocks, formed 571 million years ago, they expected to find signs of unicellular organisms, such as bacteria. What they saw—and confirmed in samples collected from another seven trips to the Serra da Bodoquena—was something even better: millimetric fossils of organisms with similar shells to modern day marine organisms. Described in an article published in June in the journal Scientific Reports, these are possibly the oldest records of shelled animals ever found in the world.

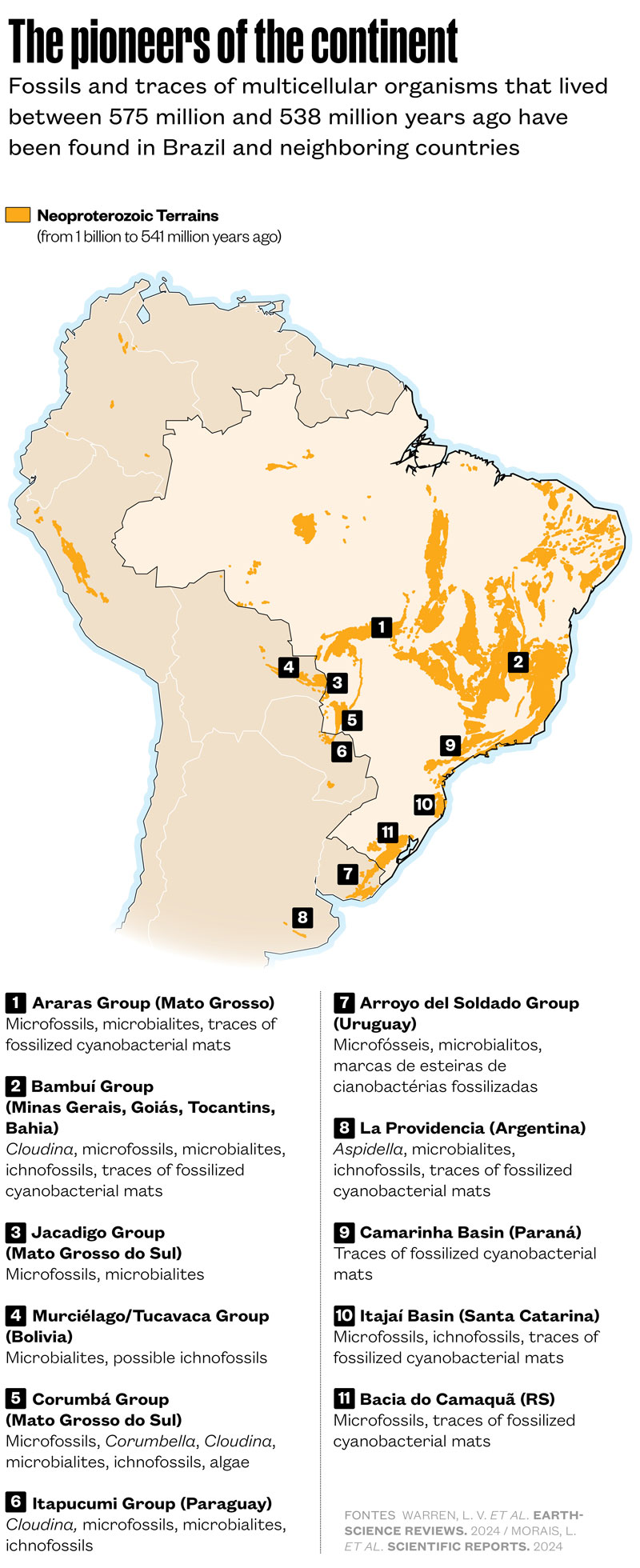

The discoveries have enriched mapping of the first multicellular organisms identified in South America, all from the Ediacaran geological period, which began 635 million years ago and ended 538 million years ago, when the subcontinent was connected to Africa. Coordinated by geologist Lucas Warren, of São Paulo State University’s (UNESP) Rio Claro campus, and described in an article published in November in Earth-Science Reviews, this mapping indicates three regions in Brazil with extremely old records—Vale do Itajaí, in Santa Catarina; the region of Corumbá, in Mato Grosso do Sul; and the north of Minas Gerais—besides areas in Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and possibly Bolivia.

For decades, geologists did not think that the Itajaí basin, an area of 1,700 square kilometers in the northeast of Santa Catarina, could harbor organisms from the so-called Ediacaran biota, made up of animals and marine algae. However, at the 1997 Brazilian Paleontology Congress, a group from Vale do Rio dos Sinos University (UNISINOS), in Rio Grande do Sul, announced the discovery of a specimen of Chancelloriidae, a family of extinct fossil animals similar in shape to sponges with hairs. This fossil was later reinterpreted as having been formed by the action of minerals, but it paved the way for other researchers to search for signs of members of this biota in the region.

Other discoveries made it clear that between 565 million and 550 million years ago, the lands today occupied by the municipalities of Blumenau, Indaial, and Apiúna in the state of Santa Catarina were covered by a shallow sea, with calm, warm waters. There lived Palaeopascichnus, possibly a protozoan, in the form of stacked rings with branches; and Aspidella, which resembled discs and would have acted as anchors for leaf-shaped structures. Fossilized tracks and trails (ichnofossils) in the form of long threads, indicators of the presence of strange beings, were also found there.

Multicellular organisms like these—the metazoans, formed by groups of different cells with specialized functions—must have also populated other shallow, warm seas that at the time covered parts of what are now Canada, the USA, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Spain, the UK, France, Italy, Russia, China, Iran, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Oman, and Australia. They had soft bodies without a shell and were found in rocks estimated to be up to 575 million years old. Recent findings suggest that animals with shells appeared in these environments some 20 million years later.

Prior to the discovery announced in June, the rocks of the Corumbá Group, which occur in Bonito, were known for the fossils of Corumbella werneri, collected in 1982 by the team of German geologist Detlef Walde from the University of Brasília (UnB), and later found in other locations. They were cnidarians, the group of jellyfish and corals, with a skeleton in the shape of stacked inverted pyramids and up to 10 centimeters (cm) in length—twice the size of animals of the same genus unearthed later in northern Paraguay.

Organisms of the genus Cloudina also lived in that area between 550 million and 538 million years ago. Likely a member of the annelids—the group that includes earthworms and marine worms called polychaetes—these Cloudina, identified in 1972 in Namibia, Africa, and later in other continents, had a conical skeleton and were up to 3 cm in length (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 199).

In the same period, in the shallow sea that covered northern Minas Gerais and gave rise to the so-called Bambuí Group, lived a poorly diversified biota, including Cloudina and groups of algae in the shape of spherical vesicles, formerly known as Bambuites erischsensii, identified by German geologist Friedrich Wilhelm Sommer in 1971.

“The presence of fossils of complex multicellular organisms in different locations with the same age suggests a possible connection with the ocean,” says Freitas, of UNICAMP. “While isolated occurrences of some of them in time and space suggest restricted environments that functioned like oases for life,” suggests Morais, who is doing a postdoctoral fellowship at UNESP.

What seems certain is that the earliest marine animals were rare, fragile, and sometimes mistaken for grooves left by one slab or rock sliding over another. The first metazoans could have formed lineages that evolved and persisted, but many became extinct, sometimes because they were not viable,” says Warren, of UNESP. “Some were strange, even lacking symmetry.” The mapping he coordinated even includes ichnofossils, traces of ancient organisms, and microbialitos, rocks formed by the metabolic activity of microbial communities (see map).

“Complete mappings of this type only existed for other parts of the world,” says Warren. In 2022, after completing his associate professorship thesis on the Ediacaran biota, he decided to regather and organize the discoveries of his own and other researchers in time and in space—such as the Cloudina in northern Minas Gerais, in 2012, and traces of marine reefs in northern Paraguay, in 2017 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 256). He soon discovered that biologist Bruno Becker Kerber, from the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS), in Campinas, was also preparing a review article about Ediacaran fauna, and they decided to work together. Slowly, other experts from Brazil, including Freitas and Morais, and from Argentina strengthened the group. Among the authors of the reconstruction of complex life in South America is US geologist Thomas Fairchild, of USP, one of the pioneers in the systematic study of these ancient life forms on the South American continent, who identified microfossils in Mato Grosso do Sul in the late1980s.

“This is the best possible proposal for organization given the available data,” observes geologist Claudio Riccomini, of both the Institute of Geosciences (IGC) and the Institute of Energy and the Environment (IEE) at USP. Biologist Antonio Carlos Marques of USP’s Biosciences Institute (IB), who also did not participate in the study, comments: “The majority of the locations where Ediacaran fauna occurred did not leave fossils, which is normal in paleontology.”

Other recent discoveries strengthen this chronology. In August, in Geosystems and Geoenvironment, geologists from UNISINOS—including Paulo Paim, who participated in finding the first fossils in the Vale do Itajaí—described microfossils of marine organisms from the late Ediacaran in the Camaquâ river basin, in the central-southern region of Rio Grande do Sul.

It is still not clear what could have caused unicellular organisms that lived during the first 3.5 billion years of Earth’s history to join together into larger and more complex structures, at almost the same time, in different parts of the planet, starting 575 million years ago. “During the Ediacaran there were changes in the chemistry of the oceans, the formation of the large supercontinent, Gondwana, and a rise in atmospheric oxygen levels,” states Warren. In the article from Earth-Science Reviews, he and other experts suggest that the shallow water environments may have created suitable temperature and salinity, and provided the nutrients necessary for these forms of life to flourish.

Luana Morais/UNESP | Bruno Becker Kerber/LNLFossils of marine animals from 571 million years ago and a yet-unknown species (images 1 and 4), and specimens of Corumbella (2) and Cloudina (3)Luana Morais/UNESP | Bruno Becker Kerber/LNL

“The existence of the metazoans depends on the marine environment and the increased oxygenation during the Neoproterozoic period, of which the Ediacaran is the final part, along with the growing supply of nutrients, likely related to the erosion of large mountain ranges,” comments Riccomini. “The problem is proving that these mountains existed during the appropriate time period. If they existed, it was not in regions close to the occurrence of fossils.”

Kerber reiterates the importance of increased oxygenation during the Ediacaran for promoting the formation and multiplication of multicellular organisms. But stresses: “In the Corumbá basin, the majority of the microfossils are in an anoxic environment [without oxygen].”

Marques expands on the uncertainty: “We don’t know if other groups or the same ones already existed before and were not fossilized. Some dates obtained using molecular clocks push the origin of the metazoans several hundred million years back compared to what fossils suggest.”

According to the researcher, many of the groups considered to be the first lineages of metazoans no longer exist: “A few still have living representatives, but they are distinct from the primitive lineages.” As the most well-known examples, he cites the group Porifera, made up of sponges, and Cnidaria. In any case, multicellular life remained confined to the sea for approximately 100 million years. The first terrestrial plants appeared around 450 million years ago and the first vertebrates with legs, the tetrapods, 397 million years ago.

The story above was published with the title “The first animals of South America” in issue 345 of November/2024.

Projects

1. Biomineralization mechanisms and paleobiology of Neoproterozoic eukaryote microfossils from the southern Paraguay Belt (n° 17/22099-0); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Ricardo Ivan Ferreira da Trindade (USP); Beneficiary Luana Pereira Costa de Morais; Investment R$599,962.91.

2. Ten million years that transformed the planet: The paleoenvironmental context of the evolution of the first animals with skeletons in the terminal Ediacaran Period (n° 18/26230-6); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Lucas Verissimo Warren (UNESP); Investment R$93,760.65.

3. Origin of Phanerozoic marine substrates and paleoenvironmental controls of the agronomic revolution in the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition (n° 23/14578-6) Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Lucas Verissimo Warren (UNESP); Investment R$236,073.70.

4. Revealing the hidden: Investigating the first animals using synchrotron microCT and deep machine learning (n° 20/11320-0); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Miguel Angelo Stipp Basei (USP); Beneficiary Bruno Becker Kerber; Investment R$522,290.22.

5. X-ray diffraction tomography and pair distribution function tomography: New tools for paleontological investigations (n° 22/06133-1) Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship Abroad; Supervisor Miguel Angelo Stipp Basei (USP); Beneficiary Bruno Becker Kerber; Investment R$304,195.85.

Scientific articles

DENEZINE, M. et al. Organic-walled microfossils from the Ediacaran Sete Lagoas Formation, Bambuí Group, Southeast Brazil: Taxonomic and biostratigraphic analyses. Journal of Paleontology. pp. 1–25. Mar. 18, 2024.

LEHN, I. et al. From the sea to the land: How microbial mats dominated marine and continental environments in the Ediacaran Camaquã Basin, Brazil. Geosystems and Geoenvironment. Vol. 3, no. 3, 100283. Aug. 2024.

MORAIS, L. et al. Dawn of diverse shelled and carbonaceous animal microfossils at ~ 571 Ma. Scientific Reports. Vol. 14, 14916. June 28, 2024.

PAIM, P. S. G. et al. Preliminary report on the occurrence of Chancelloria sp. in the Itajaí basin, Southern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Geociências. Vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 303–8. Sept. 1997.

WARREN, L. V. et al. The Ediacaran paleontological record in South America. Earth-Science Reviews. Vol. 258, 104915. Nov. 2024.

Republish