Female Brazilian filmmakers are white, wealthy, and from the Southeast, where 80% of all film producing companies in the country are located. The data that helped profile the Brazilian female film director are part of several recent studies on the subject—which has, over the last two decades, drawn increasingly more interest from not only film, but also anthropology and history researchers. While less than 1% of Brazilian film productions were directed by women from 1961 to 1971, this number increased to about 15% from 2001 to 2010. “That is still low,” notes filmmaker Paula Alves, who analyzed 3,455 films to investigate how many women were in prominent roles, such as director and screenwriter, in feature films produced in Brazil from 1960 to 2010.

For her research, developed at the National School of Statistical Sciences of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (ENCE-IBGE), Alves built a database from sources such as Dicionário de filmes brasileiros – Longa-metragem (Dictionary of Brazilian cinema – Feature films) (self-published, 2009), by Antonio Leão da Silva Neto, and the website Filme B, specialized in the Brazilian film market. In the database, she included information on fiction, documentaries, and animated films, not necessarily commercially released. Alves, who created Femina – Festival Internacional de Cinema Feminino, a film festival focused on women-led productions, was surprised by some of the numbers revealed by the study. One of them refers to the role of director of photography. “That is where women are least numerous in Brazilian cinema: just over 1% throughout the period studied, and only 3% over the last decade.” Female writers are also rare: only 13.7% of films released from 2001 to 2010 were written exclusively by women, according to the survey.

Of the 240 highest grossing Brazilian films from 1995 to 2018, 21% were directed by women

The low number of women in leadership roles in cinema is not exclusive to Brazil. In 2014, a study commissioned by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media (USA) and conducted by the University of Southern California in 11 countries revealed that, in China, 16.7% of films were directed by women; in Australia, 8.3% of films were female led. On the other hand, the study “The celluloid ceiling,” developed by Martha Lauzen, a professor of film and television at San Diego State University, found that 20% of directing, writing, producing, editing, and cinematography jobs with the 100 top-grossing films in the United States in 2019 were held by women. The Academy Awards reflect this inequality. Although they began in the 1920s, the first time a woman won an Oscar for Best Director for a feature film was in 2010: Kathryn Bigelow, for War on Terror. “In general, women struggle to achieve positions of leadership, and cinema is no different,” says producer Deborah Ivanov, former director of the Brazilian Cinema Agency (ANCINE) and now leader of More Women in the Brazilian Film Industry, a group established last year by 90 industry professionals. “It is a vicious cycle: men are hired to direct and write feature films because they are more experienced, while women remain in the background because they are less experienced in directing.”

The situation is even worse for Black women, as pointed out by political scientist Marcia Rangel Candido, associated researcher at the Affirmative Action Multidisciplinary Studies Group, from Rio de Janeiro State University (GEMAA-UERJ). Established in 2014, the group records diversity in Brazilian cinema. Its latest survey showed that 21% of the directors of the 240 highest grossing Brazilian films from 1995 to 2018 were female. None of them were Black. “This inequality cannot be explained away by a lack of professionals in the Brazilian film market: Black women are out there and report facing challenges getting funding and distribution,” says Candido. “Research shows that the Brazilian film market is dominated by white men and does not represent our diversity. The goal is that these data help foster more public policies on gender and racial equality in the country.”

Publicity / Edileuza Penha de Souza

A still from the short film Filhas de lavadeiras, by Edileuza Penha de SouzaPublicity / Edileuza Penha de SouzaHistorian Edileuza Penha de Souza, from the Center for Afro-Brazilian Studies at the University of Brasília (UnB), agrees. In 2012, during her PhD research, she noticed that her findings for a chapter on Black cinema contained no female directors of feature-length films. “As a Black woman, I was very distressed to discover such a gap, and even though this was not the main focus of my research, I decided to dive deeper into the history of Brazilian cinema in search of Black female directors,” recalls Souza, a documentary filmmaker herself and a professor at the Recanto das Emas campus of the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of Brasilia (IFB), which focuses on technical education in film. On a website about women in Brazilian cinema, she came across a photo of Adélia Sampaio and, through social media, got in touch with the filmmaker—a Minas Gerais native based in Rio de Janeiro.

According to the researcher, Sampaio is the first female Black filmmaker in Brazil. “She started out in the film industry in the late 1960s, as an operator at Difilm, a Cinema Novo (New Cinema) distributor founded by producer Luiz Carlos Barreto. She then wrote scripts and directed short films. In 1984, she commercially released the feature film Amor Maldito (Cursed Love)—a first for a Black woman up until that point.” Since 2016, Souza has been organizing the Adélia Sampaio Competitive Black Cinema Exhibition at UnB. “Our goal is to give visibility to the work of Black filmmakers, who still face the most significant challenges when seeking support for their films,” she explains. “Adélia’s career is inspiring in this sense. At 76, she is still fighting to make her films,” points out the director of Filhas de lavadeiras (Daughters of washerwomen), which won Best Brazilian Short Film in the international documentary festival It’s All True, in 2020.

Indigenous filmmakers are even rarer. In her PhD thesis on gender and racial hierarchies in contemporary filmmaking, defended in 2019 at the ENCE-IBGE, Paula Alves found that, of the 1,851 directors of 2,558 films analyzed from 1995 to 2016, only eight (0.4%) of them were indigenous: seven men and one woman. “In Brazil, the interest in films made by indigenous women is very recent,” says Clarisse Alvarenga, from the Federal University of Minas Gerais School of Education (FAE-UFMG). “Only in the last decade have they gained prominence and made a significant number of films.” During her postdoctoral studies at the National Museum, Alvarenga studied the production of Brazilian filmmakers, including Ayani Huni Kuin, from the Huni Kuin people, and Patricia Ferreira Para Yxapy, from the Mbyá-Guarani people, as well as Navajo filmmaker Arlene Bowman, who lives in California, United States. Honored at the 2020 Cabíria Festival – Mulheres & Audiovisual (Cabíria Festival – Women & Film), in São Paulo, Yxapy showed 11 films at the event, including Teko Haxy – Ser imperfeita (Teko Haxy – Being imperfect) (2018), co-directed with researcher and visual artist Sophia Pinheiro. “The growing dialogue between indigenous women and researchers, curators, and other filmmakers makes cinema more diverse, more complex, and helps give these women voices and more opportunities to make films,” says Alvarenga.

Sophia Pinheiro / Publicity

Director Patrícia Ferreira Pará Yxapy, from the Mbyá-Guarani peopleSophia Pinheiro / PublicityAcademic criticism on women-directed films flourished in the 1970s in Europe and the United States, boosting scientific research on the subject. “This took place alongside an increase in the number of women working in film, including in leadership positions,” says Karla Holanda, professor of Film and Audiovisual Studies of the Fluminense Federal University (UFF). Holanda believes one reason for this was the creation of the International Women’s Year, in 1975, and the Decade for Women (1976–1985), both established by the United Nations (UN). “By encouraging artistic and cultural projects, these initiatives helped women gain prominence around the world, including in the movies,” she points out. “Another positive point was the establishment of film programs in Brazilian universities, such as the University of São Paulo, in 1967, and UFF, in 1968.”

In Brazil, a pioneering study was released in 1982: the book As musas da matinê (Matinee muses), by Elice Munerato and Maria Helena Darcy de Oliveira, published by Rioarte. In it, the two researchers list 21 feature films made by women and commercially released in the country before 1979, such as O ébrio (The drunkard) (1946), by Gilda de Abreu (1904–1979), and Mar de rosas (Sea of roses) (1977), by Ana Carolina. Later, in 1989, the School of Communication at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Image and Sound published Quase catálogo 1: Realizadoras de cinema no Brasil (1930–1988) (Almost catalogue 1: Female filmmakers in Brazil), organized by Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda, today a UFRJ professor emeritus.

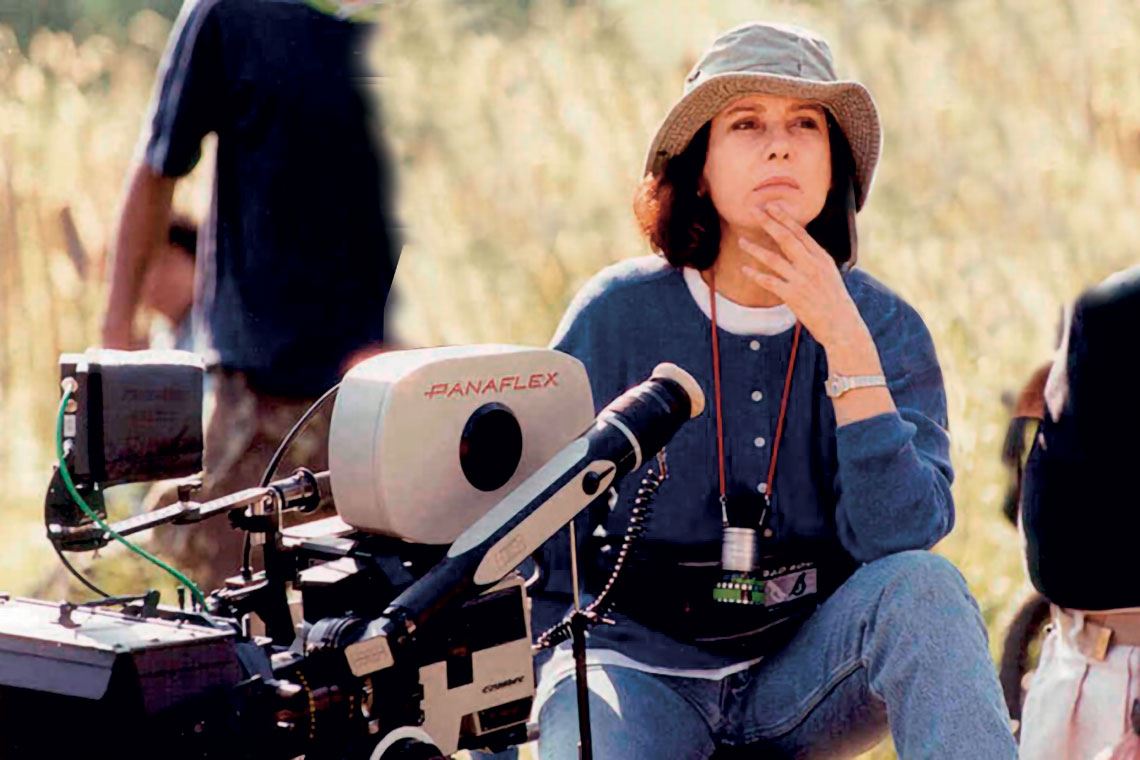

Vantoen Pereira Jr

Filmmaker Ana CarolineVantoen Pereira JrAccording to Karla Holanda, these were essential to many academic papers on the subject. “Most of this research is still conducted by women, but I have noticed more and more men developing an interest in the cause. This is great, because recognizing the role of women in cinema—omitted throughout much history—is in the interest of everyone,” she argues. In Mulheres de cinema (Women of film) (Numa Editora, 2019), a book edited by the expert, two of the 22 chapters have been authored by men.

Researcher Luiza Lusvarghi, from the Film and Audiovisual Genres Study Group (GENECINE), of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), more courses specifically focused on women filmmakers in undergraduate film programs in Brazil would drive interest in the subject. “This discussion must start early in the training of these professionals, regardless of their gender,” she says. “We know very little about female Brazilian filmmakers. It is difficult to collect data on them.” The issue became clear for the researcher when organizing the book Mulheres atrás das câmeras: As cineastas brasileiras de 1930 a 2018 (Women behind the camera: Brazilian filmmakers from 1930 to 2018) (Estação Liberdade, 2019) with Camila Vieira da Silva. Developed within the Brazilian Film Critics Association (ABRACCINE), the book contains 27 articles and a dictionary on 263 female directors who have released at least one feature film commercially or at film festivals in Brazil. “Many make only one film and, due to the challenges they encounter, leave their film career behind.”

National Archive / Wikimedia Commons

Filmmaker Gilda de AbreuNational Archive / Wikimedia CommonsOne of these directors is Cleo de Verberena—a pseudonym of São Paulo native Jacyra Martins da Silveira (1904–1972). Considered the first Brazilian female filmmaker, she directed and starred in the 1931 police thriller O mistério do dominó preto (The mystery of the black domino), at the end of the silent film era. “In the 1930s, Brazilian women were spectators or, at most, actresses in film productions. Not coincidentally, the directing debut of a woman was seen by critics as exotic,” explains Marcella Grecco de Araujo, who is studying Verberena’s career for her PhD at the USP Post-graduate Program in Media and Audiovisual Processes. Released by Epica-Film, a production company that belonged to the director and her husband, Cesar Melani (1903–1935), the film was Verberena’s only directing work. Three years later, she abandoned her artistic career. According to Araujo, the film was not well received and caused “huge financial loss.” “Cleo de Verberena had already been forgotten by the 1930s. Although brief, her artistic career helps us understand the beginnings of Brazilian cinema,” she concludes.

Project

Cleo de Verberena: The first Brazilian female filmmaker (no. 17/13760-4); Grant Mechanism Doctoral (PhD) Fellowship; Principal Investigator Esther Império Hamburger (USP); Beneficiary Marcella Grecco de Araujo; Investment R$162,702.54.

Books

HOLANDA, K. (org.). Mulheres de cinema. Rio de Janeiro: Numa, 2019.

LUSVARGHI, L. and SILVA, C. V. da (orgs.). Mulheres atrás das câmeras: As cineastas brasileiras de 1930 a 2018. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2019.