To help improve Brazil’s public safety policies, characterized by combat techniques derived from the military culture and repressive aspects of criminal law, academic researchers previously focused on different manifestations of violence in society begin to look at one specific type: the challenges associated with police organizations. At the same time, public safety officers have been investing in academic careers as a path to find solutions to problems faced in their daily lives and organizations. In a context of truncated communications, in recent years professionals from security institutions and academia have looked for opportunities to develop contact initiatives. Recent studies resulting from this effort propose solutions to challenges involving urban violence, use of lethal force by police, and the death of officers.

In Brazil, the first projects to foster innovation in police education, through partnerships between universities and public safety organizations, began to appear about 20 years ago. According to sociologist José Vicente Tavares dos Santos, from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), one of the milestones was the 2003 establishment of the National Network of Advanced Studies on Public Safety, supported by partnerships with 60 universities to train specialists in the field. “More than 10,000 civil and military police officers took part in the initiative,” he recalls. In 2015, the network set up a project to grant 600 students professional master’s degrees with a focus on citizen safety, including strategies to reduce crime rates while training police officers in human rights and diversity issues. Tavares dos Santos cites five professional master’s programs on citizen safety currently available in Brazil, offered by UFRGS, Amazonas State University (UEA), Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Federal University of Pará (UFPA), and Minas Gerais State University (UEMG).

The researcher explains that reforms adopted in the 1990s by American police inspired these initiatives, which moved away from the repressive model that drove their work in previous decades. “The changes were intended to encourage the development of a police force that was close to the communities, seeking alternatives to fight crime,” says Tavares dos Santos. In New York, for example, social projects were established offering sports classes and libraries in areas with high violence and crime rates. Police performance protocols were reformed, and their permission to use firearms was restricted.

“We currently have two distinct concepts of what police work should be, one of which is guided by the concept of citizen safety. The second modality, which prevails in the design of Brazil’s public policies, involves a repressive bias and dictates the militarization of procedures,” compares Tavares dos Santos. Another milestone, says the sociologist, was the 2003 establishment of the National Curriculum Matrix through a partnership between academic researchers and the National Secretariat of Public Security, linked to the Ministry of Justice. The initiative provides for the inclusion of courses on human rights and diversity in police academy programs. “The challenge for democracy is establishing an approach to citizen safety where the police officer also acts as a protector of rights,” he points out.

Intending to discuss the formation of a police identity and analyze changes made to the curricula of police academies in Rio de Janeiro after the establishment of the National Curriculum Matrix, sociologist Paula Poncioni, a retired professor from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and a member of the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety (FBSP), published the book Tornar-se policial: O processo de construção da identidade profissional do policial nas academias de polícia (Becoming a police officer: Building the professional identity of police officers in police academies – Appris Editora, 2021). The book addresses the results of different studies carried out since the late 1990s in partnership with institutions such as the Center for the Study of Violence at the University of São Paulo (NEV-USP), the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA), and FBSP, a nonprofit and nongovernmental organization dedicated to fostering technical cooperation for public safety. From 2002 to 2012, Poncioni carried out field research involving the civil and military police forces, following the careers of a generation of officers in Rio de Janeiro over a span of ten years. She found that, even after improving the resumes of instructors at police academies, they are still teaching new officers more traditional techniques, emphasizing repressive and punitive strategies to fight crime. “The formal content of the curricula has no effect on police practices,” she says. Poncioni also states that, despite the mutual interest of academia and police organizations in studying and figuring out solutions to these problems, there is still a long way to go before this cooperation results in any significant change in the police hierarchy.

When it comes to training, jurist and anthropologist Roberto Kant de Lima, from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), explains that applicants for a military police officer job must have a bachelor’s degree in law. “Both military and legal education are instructional and dogmatic, using authority as an argument to squash questions and resolve conflict. This means the work of police officers is contaminated by the repressiveness of criminal law, or of the military ethos,” he claims. Ethos is the set of customs or behavioral traits typical of a community or people.

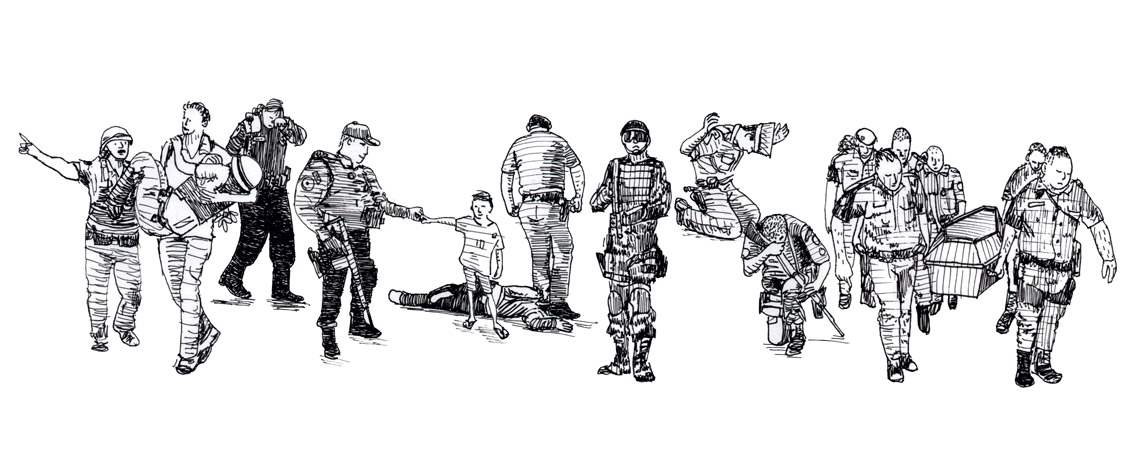

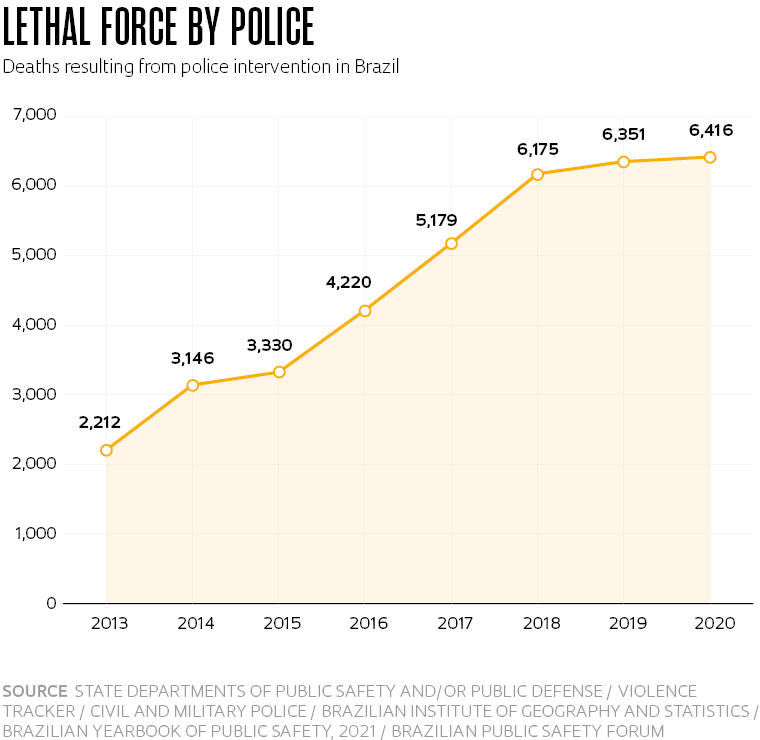

One of the consequences of this repressive approach, according to Kant de Lima and Poncioni, is high rates of police violence. Published this year, the latest edition of the Public Safety Yearbook, organized by FBSP, indicates that 6,400 people were killed because of police interventions in 2020. This is the highest historical number since the organization began tracking deaths in 2013. Black individuals made up 78.9% of their victims. In comparison with 2019, the document also shows that the number of deaths resulting from police operations increased in 18 of Brazil’s 27 states, revealing a spread of police violence across the country. At the same time, in nine of the states, this number decreased.

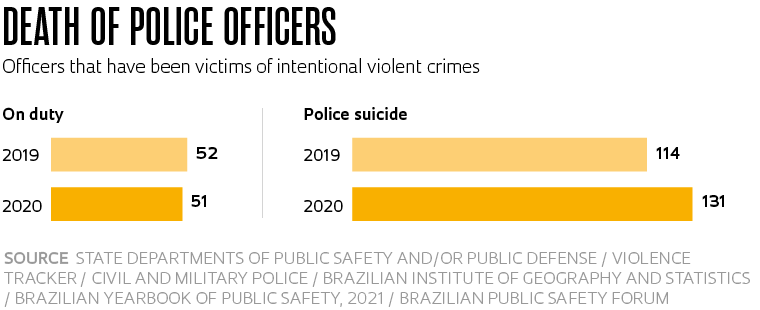

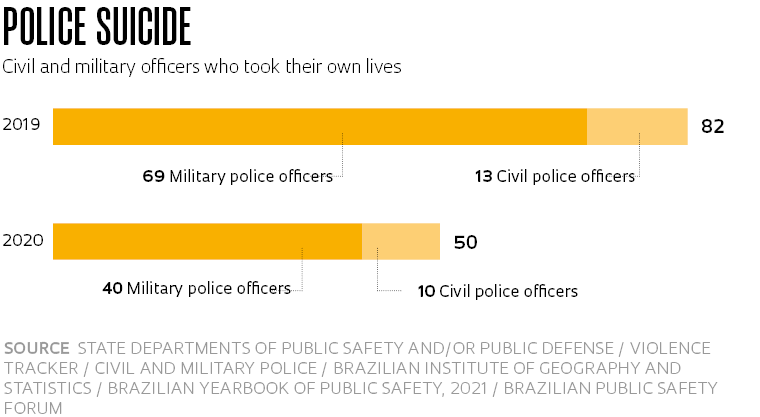

Such violence also affects the lives of the officers and their families, as sociologist Maria Cecília de Souza Minayo, from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), found when conducting two censuses of civil and military police officers in Rio de Janeiro in 2013 and 2018. By analyzing their demographic profile, living conditions and health data, Minayo found that officers who work in the most violent areas are also those who face more serious mental health problems. “Many have depression and chronic insomnia, causing strain in their family life, which can aggravate their aggression. The police officers cause a feedback loop of the violence they face and reproduce it in their confrontations,” says Minayo. One of the most memorable moments she experienced during the research was when hearing about how police officers feel about being obliged to attend their colleagues’ funerals. “I remember a sergeant who told me he had lost a friend in a conflict. He missed three days of work, running the risk of being arrested for contempt, but he stated he would rather be arrested than to have to walk alongside his colleague’s coffin,” she recalls. “Attending the funerals of fellow officers is one of the greatest ordeals for police officers, who often feel guilty or see the experience as a harbinger of their own death.” Minayo also emphasizes that police officers who experience violent situations have no opportunity to process the experience, as most do not receive psychological and social support.

Motivated to understand the effects of public safety policies on the health of officers, Lieutenant Colonel Adriane Batista Pires Maia obtained a PhD this year at the FIOCRUZ Department of Violence and Health. An oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the State Secretariat of Military Police for the State of Rio de Janeiro, she conducted an epidemiological study with data from military police officers operated on because of gunshot wounds at the Central Hospital of the Military Police, from 2003 to 2017. “The majority of individuals shot by firearms are soldiers, corporals, or sergeants wounded within the first 10 years of their career. Those who survive face lifelong aftereffects,” she states. During the period covered by the study, 778 surgeries were performed, and all patients were male with an average age of 34. “Loss of limbs was the most common long-term consequence, as well as facial esthetic impairment, reports of insomnia, and difficulty in relationships,” says Maia. According to data from her research, 75% of officers shot by firearms become unfit for work. The highest rates of police mortality are registered on the officers’ days off, when they are armed and react to attempted crimes against them or other people, which is linked to the belief that they must always intervene. Another survey carried out this year by FBSP indicates that around 47,000 police officers, firefighters, and municipal guards across Brazil work as private security to supplement their income, which is prohibited by law and can result in death outside their official working hours. “As for morbidity cases, meaning officers are injured by firearms but do not die, these happen more frequently during their working hours. Therefore, I consider that morbidity caused by firearms is a direct consequence of the actions of police officers,” she argues.

In addition to aspects of police academy training, Poncioni, from UFRJ, identified that the construction of a police officer’s professional identity is associated with the notion of hero or soldier. “Many see themselves, and are seen by others, as heroes rather than workers with the right to work,” says the sociologist. Her view is corroborated by Rafael Alcadipani, from the São Paulo School of Business Administration at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV-EAESP). “Identity plays a central role in this profession. Police officers often see themselves as heroes because it helps them face dangerous situations,” suggests Silveira.

Juliana RussoAccording to the researchers consulted for this article, expanded communications between police organizations and the academic world constitutes a promising path to improve the nation’s public safety policies. However, anthropologist Susana Durão, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), points out obstacles to this. “There is a mutual ignorance of each other’s cultural context. Studies in the field of violence sociology, which encompass different perspectives on the relationships and social structures of violence and criminality in Brazil, have predominated academia. Analyses of police organizations and police practices are less frequent. Officers believe that studies on the sociologies of violence and police violence point to problems, but do not provide solutions,” she says. On the other hand, researchers claim that police officers are not open to academic studies. The anthropologist leads a committee at the Zumbi dos Palmares University, which includes members of the Public Safety Secretariat of the State of São Paulo, civil and military police officers, municipal guards, and representatives from private safety sectors. “We established the committee to track police training in the state and identify humanist and antiracist content in the programs. Based on this diagnosis, the goal is to propose improvements to the entire system,” she explains.

Juliana RussoAccording to the researchers consulted for this article, expanded communications between police organizations and the academic world constitutes a promising path to improve the nation’s public safety policies. However, anthropologist Susana Durão, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), points out obstacles to this. “There is a mutual ignorance of each other’s cultural context. Studies in the field of violence sociology, which encompass different perspectives on the relationships and social structures of violence and criminality in Brazil, have predominated academia. Analyses of police organizations and police practices are less frequent. Officers believe that studies on the sociologies of violence and police violence point to problems, but do not provide solutions,” she says. On the other hand, researchers claim that police officers are not open to academic studies. The anthropologist leads a committee at the Zumbi dos Palmares University, which includes members of the Public Safety Secretariat of the State of São Paulo, civil and military police officers, municipal guards, and representatives from private safety sectors. “We established the committee to track police training in the state and identify humanist and antiracist content in the programs. Based on this diagnosis, the goal is to propose improvements to the entire system,” she explains.

Between two worlds

Sitting in his office at the 21st Battalion of the Metropolitan Military Police, at Parque da Mooca, in São Paulo, Lt. Col. Alan Fernandes recalls one of the most challenging experiences in his 20-year career straddling the policing and academic worlds. In 2013, in partnership with sociologists Esther Solano and Liana de Paula, from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), he helped organize a seminar on public safety at the Foundation School of Sociology and Political Science of São Paulo (FESPSP), where he was a graduate student at the time. The event had the goal of bringing together 30 military police officers to debate with academic researchers. However, because they were prohibited from entering the educational institution with a firearm, most refused and, in the end, only eight of them attended. “The refusal to go in unarmed is related to the officer’s identity. Carrying a gun is part of the ethos of the profession,” he explains. With a PhD in public administration and government from FGV-EAESP, Fernandes considers, on the other hand, that research on police victimization carried out since 2010 began sensitizing officers about the importance of communicating with the academic world. During his PhD, completed in 2021, he studied the historical development of police strategies and ideologies, as well as different models of public safety policies. Regarding the impacts of academic training on daily work, he provides an example with the changes in the way officers handle conflicts in “bailes funk” (parties or establishments that play Rio de Janeiro funk music). “The traditional police response to these events was to use force and repressive strategies to disperse participants. My PhD research helped me formulate alternative solutions, and I started to encourage police officers to act as mediators of conflict,” he says. While looking at a large map depicting the jurisdiction of the battalion he commands, Fernandes cites research topics that he considers relevant to the daily life of police officers, including the impact on neighborhood crime rates, the installation of cameras in the streets, and the construction of headquarter buildings.

Scientific articles

DURÃO, S. and COELHO, M. C. Do que fala quem fala sobre polícia no Brasil? Uma revisão da literatura. Análise Social, LV (1), no. 234, pp. 72–99, 2020.

MAIA, A. B. P. et al. As marcas da violência por arma de fogo em face. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. Vol. 87 (2) pp. 145–51, 2021.

MAIA, A. B. P. et al. Ferimentos não fatais por arma de fogo entre policiais militares do Rio de Janeiro: A saúde como campo de emergência contra a naturalização da violência. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, Vol. 26 (5), pp. 1911–22, 2021.

Books

LIMA, R. K de. A polícia da cidade do Rio de Janeiro: Seus dilemas e paradoxos. Rio de Janeiro: Amazon, 2019.

PONCIONI, P. Tornar-se policial: O processo de construção da identidade profissional do policial nas academias de polícia. Curitiba: Appris Editora, 2021.

TAVARES DOS SANTOS, J. V. et al (ed.). Violência, segurança e política – Processos e figurações. Porto Alegre: Tomo Editorial, 2019.

TAVARES DOS SANTOS, J. V. Ambivalências do ensino policial: Educar ou treinar? Um estudo em sociologia da conflitualidade. (Ambivalence around police education: Education or training? A study of the sociology of conflict). In: ADORNO, S. and LIMA, R. S. (Ed.). Violência, polícia, justiça e punição: Desafios à segurança cidadã. São Paulo: Alameda, 2019, pp. 231–302.