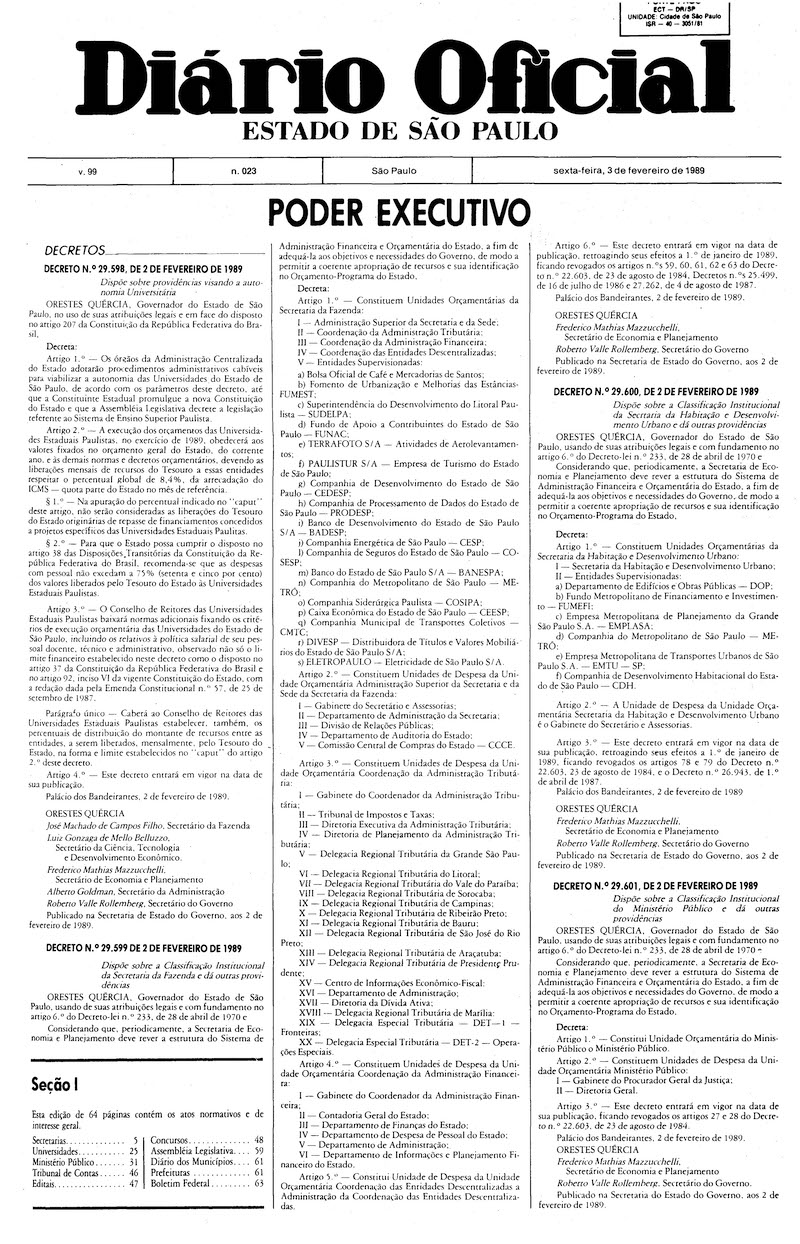

The legal and budgetary framework that provided funding stability to state universities in São Paulo has now completed its third decade in force. On February 2, 1989, a decree by the then governor of São Paulo, Orestes Quércia (1938–2010), granted financial autonomy to the University of São Paulo (USP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and São Paulo State University (UNESP), and allocated a fixed percentage of 8.4% of state sales tax (ICMS) to funding for the three institutions. The Council of Deans of State Universities in São Paulo (CRUESP), created two years earlier, was tasked with managing the distribution of funding, with USP initially receiving 4.46%, UNICAMP 2%, and UNESP, 1.94%.

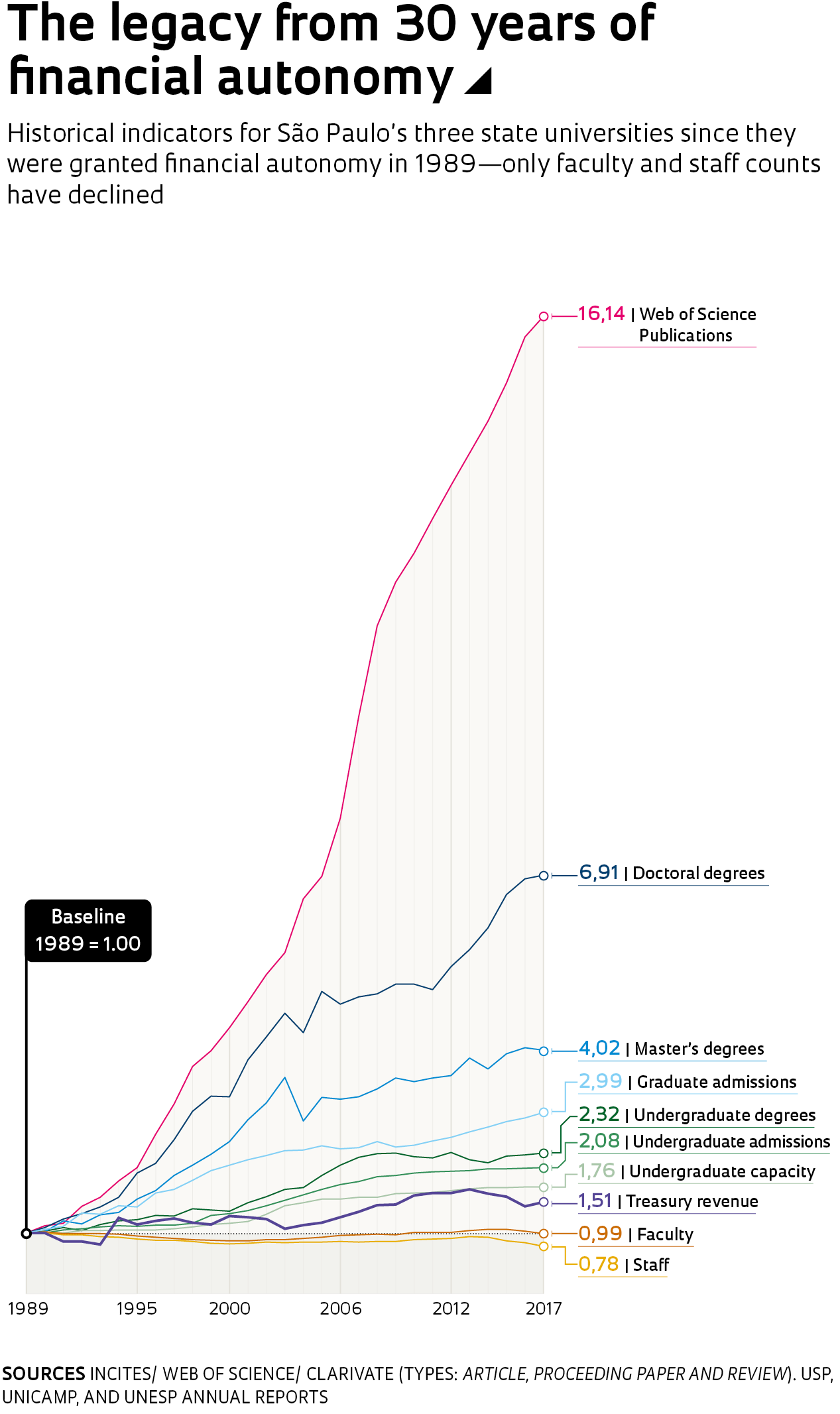

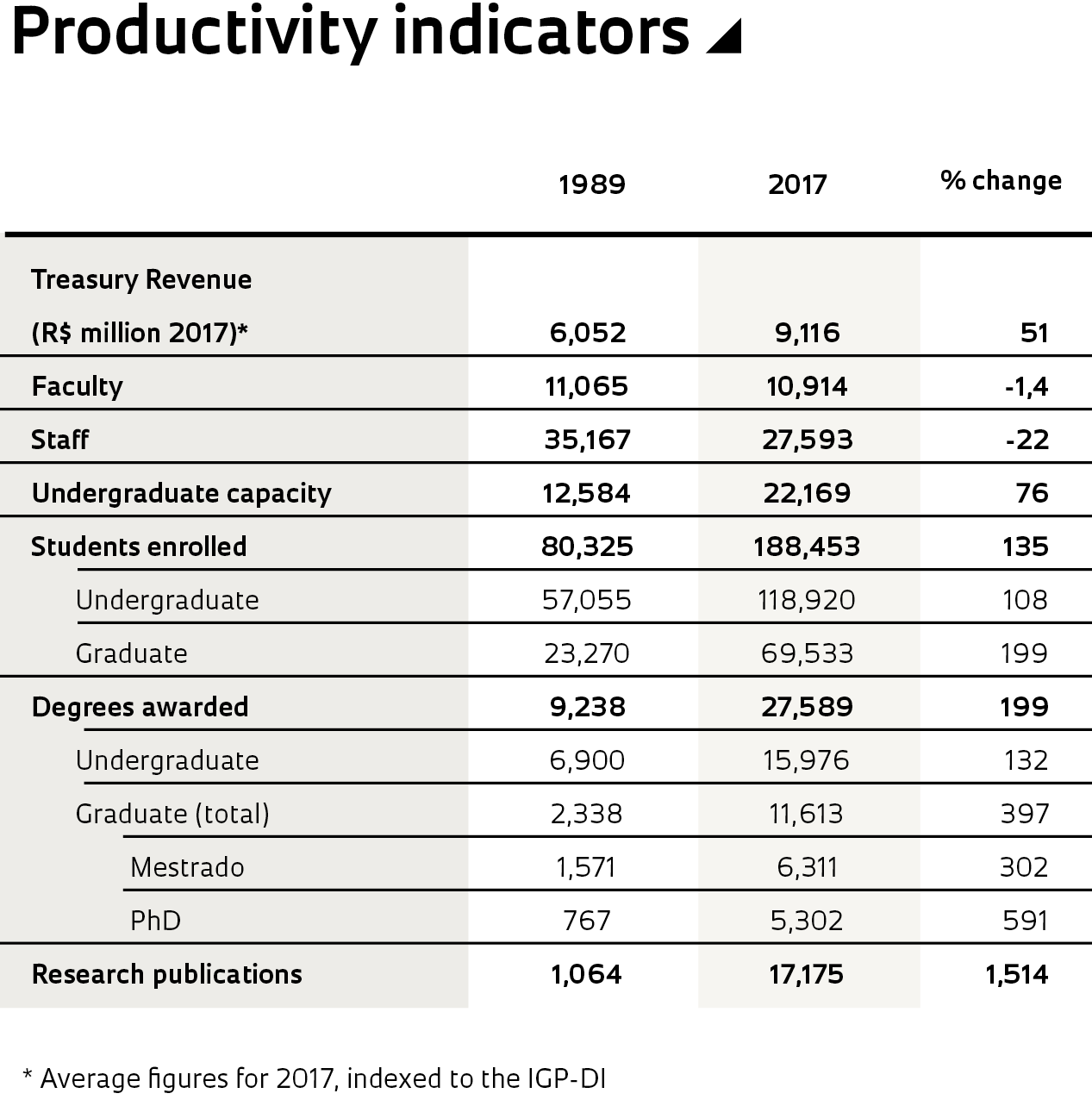

The 1989 decree became a milestone in higher education in Brazil as a model that succeeded in bolstering and strengthening the country’s three largest research universities, and in providing academic freedom while maintaining competition for funding with other government agencies and departments. Today, USP, UNESP, and UNICAMP together produce 35% of all research indexed on the Web of Science platform. But for all these benefits, the framework introduced by the decree has remained unique to São Paulo; no peer states have since adopted similar principles, and no federal universities have been granted financial autonomy. It is also curious that the rules were introduced through a simple decree, whereas originally there had been plans to enact them through the State Constitution or ordinary legislation.

– Tools for planning the future

– The race for excellence

– Fuel for innovation

– Expanding student numbers

But the model has been reaffirmed each year in the annual budgets passed by the Legislative Assembly, and has been ratified by all state governors since, two of whom—Luiz Antonio Fleury Filho and Mário Covas (1930–2001)—in fact increased the percentage of ICMS tax allotted to universities, which since 1995 has stood at 9.57%. “This has set São Paulo apart from other states and illustrates the importance that São Paulo society attaches to universities,” says linguist Carlos Vogt, who served as dean at UNICAMP between 1990 and 1994. “No one has dared to desecrate this sanctuary.”

The granting of financial autonomy to state universities in São Paulo occurred in the historical context of Brazil’s redemocratization and, in particular, the passage of a new Federal Constitution. Article 207 of the 1988 Constitution calls for “educational, scientific, administrative, financial, and asset-management autonomy” at universities and requires them “to adhere to the principle of inseparability of education, research, and extension.” Physicist José Goldemberg, who served as dean of USP between 1986 and 1990, notes that the Constituent Assembly’s initial draft of this article contained a proviso that could have delayed implementation, or prevented it altogether. “The last part of the article stated that “autonomy shall be implemented as shall be provided by law.” This would have consigned the rules to ordinary legislation and could have delayed implementation, as would indeed occur with many other articles of the Constitution,” he recalls. Goldemberg was a close acquaintance of the deputy rapporteur of the Constituent Assembly, senator Mário Covas—he had worked with him during the André Franco Montoro administration (1983–1987)—and convinced him of the importance of removing the proviso and maintaining autonomy as a general rule. “The final draft removed the need for subsequent regulation,” says Goldemberg.

While the autonomy decree makes reference to Article 207 of the Constitution, Governor Orestes Quércia also had his own and contextual reasons for his decision. The crisis in the 1980s had led to runaway inflation and a succession of economic plans that tried, in vain, to contain it. And the resulting erosion of workers’ wages had fueled strikes that paralyzed state universities in São Paulo. “The governor felt that the pressure for funding and wage increases would be recurring. He was unfamiliar with the academic environment, but intuition led him to allocate a percentage of tax revenues and to leave to deans both the benefits and the burden of managing funds,” says Frederico Mazzucchelli, a professor at the Institute of Economics at UNICAMP, who previously served as State Secretary of Economics. Mazzucchelli recalls how Quércia confided his idea to him during a flight. “The governor said to me: ‘We give them the money and our troubles are over.’”

The university and research agenda gained traction in the 1980s and was supported by the Legislative Assembly, recalls Aloysio Nunes Ferreira

Mazzucchelli sought out Science and Technology Secretary Luiz Gonzaga Belluzzo, whom he knew from UNICAMP, and the pair got to work on developing a draft. “The initial reaction from deans was a mixture of surprise and suspicion; only the dean at UNESP, Jorge Nagle, was enthusiastic from the outset. They needed to be convinced that this was important,” he recalls. There were also opposing voices within the government to contend with. The then Secretary of Administration, Alberto Goldman, was opposed to committing tax revenues on the grounds that it would impose the agendas of certain interest groups on democratically elected governments. After several rounds of discussions with deans and secretaries, a formula allocating 8.4% of ICMS tax revenue was arrived at; this was equivalent to the average amount of funding the universities had received in the previous three years. “UNICAMP Dean Paulo Renato Souza [1945–2011], who had served as secretary of education years before, helped make the calculations,” Goldemberg recalls.

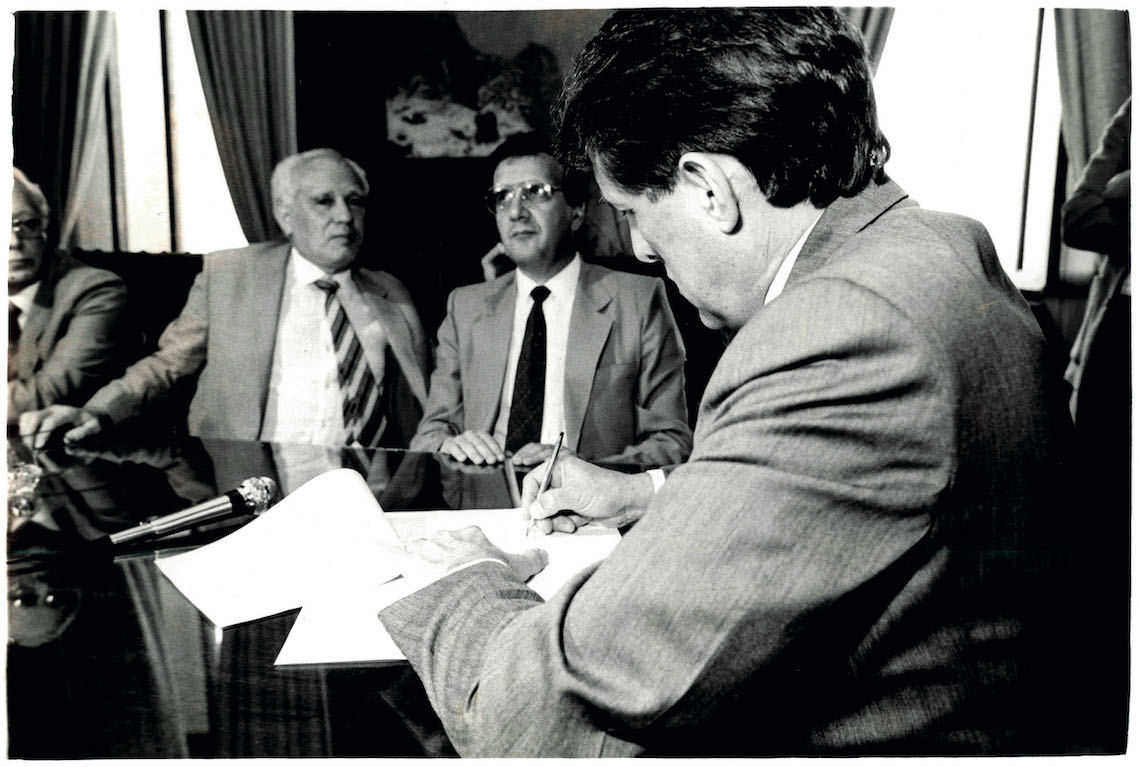

In February 1989, when the draft was ready, the governor called the deans to his cabinet and signed the decree into law. Geologist Paulo Milton Barbosa Landim, who had just replaced Nagle as dean of UNESP, recalls that the governor mentioned the pressure he had received from universities as one of his motivations. “He stated up front that, since universities had academic independence and he could not interfere in their management, then they should also have financial independence, which meant the deans would be left to deal with issues related to professors’ salaries.”

Carlos Vogt believes the discussion on the governor’s motives is secondary: “What’s important to remember is the context surrounding the financial autonomy decree and the governor’s merit in signing it. It’s a legacy he left that continues to yield important dividends for universities today.” Vogt believes the framework drew inspiration from a previous initiative in the state of São Paulo—the creation of FAPESP in 1962, with funding then provided by a government endowment fund and an allocation of 0.5% of state tax revenues to fund research. “FAPESP was born out of a movement within São Paulo’s 1947 Constituent Assembly that valued intellect, science, and culture. It created a paradigm that set the state apart and catalyzed a movement toward establishing financial autonomy at universities,” says Vogt, who served as chairman of the foundation between 2002 and 2007.