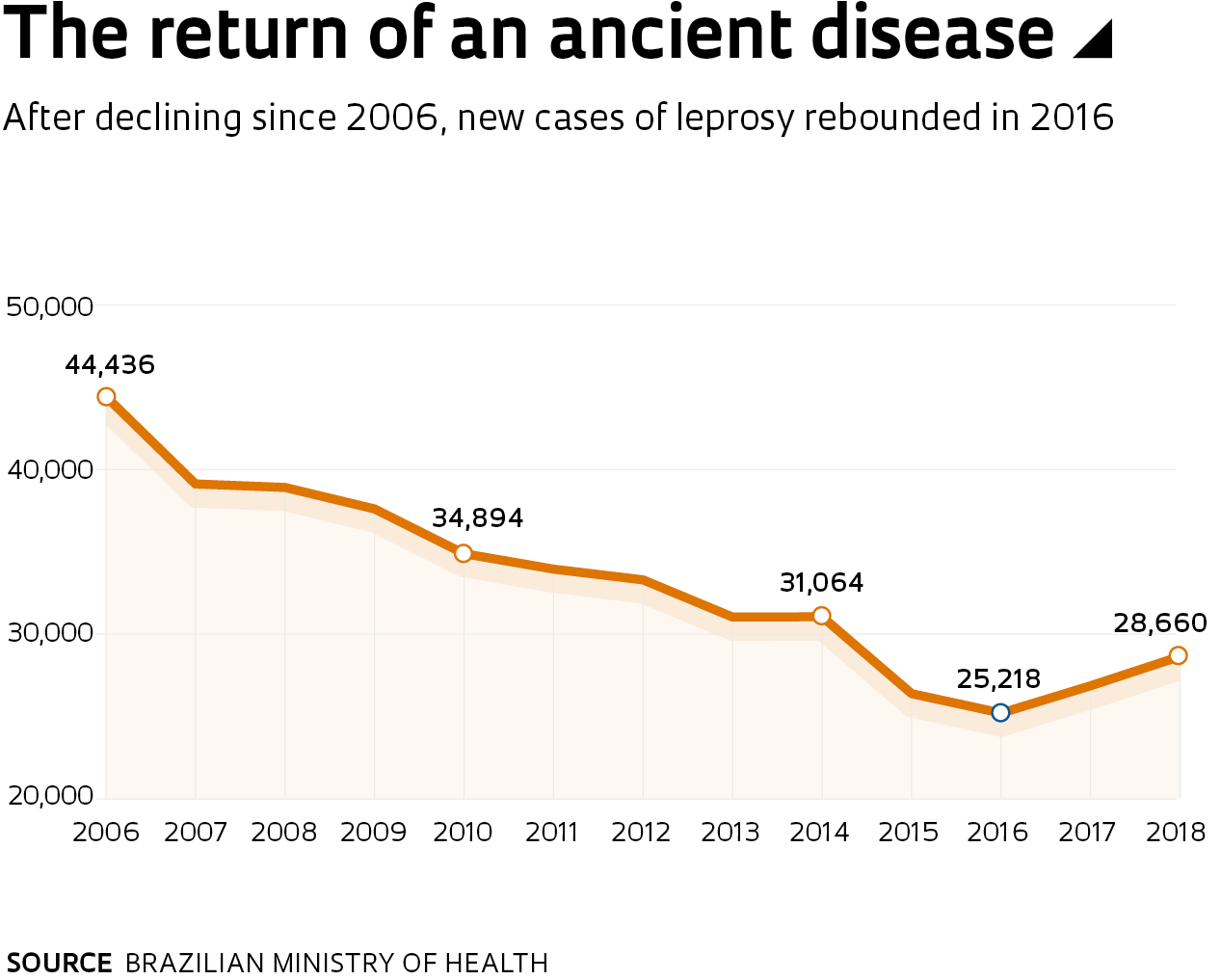

After a ten-year decline, new leprosy cases have been on the rise in Brazil for two consecutive years. Last year alone, 28,660 people received a diagnosis of leprosy, approximately 1,800 more than in 2017 and 3,500 more than in 2016, according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The disease is most prevalent in the Northeast, Midwest, and North of Brazil, with these regions accounting for nearly 85% of cases in the country due to poor housing and sanitation, the primary culprits in the transmission of the disease-causing agent, the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae. The high rates of resistance to antileprosy drugs in Brazil are an added concern. According to data from the United Nations (UN), resistance to one of these drugs, dapsone, is as high as 13.3% in Brazil. Resistant patients, who are unresponsive to drugs, suffer from increasingly ill health and may even die. In addition to skin lesions, the disease can also cause neural damage.

Veterinarian Patrícia Rosa, director of the Research and Education Division at the Lauro de Souza Lima Institute (ILSL) in Bauru, one of the foremost leprosy treatment centers in the state of São Paulo, says the increase in new cases is the result of deficient efforts to prevent and diagnose the disease. “Leprosy is a slowly progressive disease that is difficult to diagnose,” says the researcher, one of the authors of a study that found the highest rate of resistance ever described for this disease in a small town in Pará. “Health professionals need to be well trained to identify the symptoms before the disease progresses into a more serious condition,” she explains. But in much of the country this is not the case. “The remotest regions suffer from a lack of health professionals with the training to make an early diagnosis.”

The Brazilian Ministry of Health disagrees with this view, however. In an email to Pesquisa FAPESP, it attributed the recent surge in leprosy cases to enhanced and intensified surveillance which, it says, results in more new cases of the disease being reported. “Brazil’s approach to combating leprosy is based on actively seeking out cases for early diagnosis, providing timely treatment, and preventing incapacitation,” the email read.

More than 200,000 new cases are reported globally each year, with 1 out of 10 new cases reported in Brazil, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). This places the country second globally for new cases, behind only India. The bacterium is transmitted by direct contact with droplets that become airborne when an infected person exhales, coughs or sneezes. The treatment for the disease—based on a combination of the antibiotics dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine—is simple, free, and effective, but lengthy. It can take from 6 to 12 months, which sometimes results in patients abandoning their treatment prematurely. These three drugs have been used in combination in multidrug therapy since the 1980s. For many years, the strategy proved effective and helped to reduce the rates of new cases globally, but since 2005 the previously declining prevalence rates have stagnated.

A possible explanation for the growing number of new cases is that the bacterium may be becoming resistant to drugs. Data collected from different countries indicates that 2% to 16% of leprosy cases are unresponsive to treatment. In a late 2018 paper in Clinical Microbiology and Infection, researchers from the World Health Organization (WHO) analyzed 1,932 cases of leprosy in 19 countries and found an average resistance of 8%—in Brazil, resistance to rifampicin is 9% and resistance to dapsone is 13.3%. But in some regions of Brazil, resistance rates are even higher.

The case of vila do prata

Between 2009 and 2017, a group led by Marcelo Távora Mira, a biochemist at the School of Medicine at the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná (PUC-PR), and Marcos Virmond, a surgeon and director at ILSL, examined 670 of the nearly 3,000 residents of Vila de Santo Antônio do Prata, a town in Pará, northern Brazil. Between 1924 and 1962, the town had been home to one of the largest leper colonies in the North and Northeast. During their visits, the researchers documented 42 cases of leprosy: 19 were people who had been infected for the first time and 23 were residents who had had the disease in the past. Biopsies obtained from 37 individuals showed that 43% were resistant to at least one of the antibiotics used in treating the disease.

Even more alarming was the discovery that one-third of resistant patients had resistance to not only one, but two of the components of the multidrug therapy regimen, dapsone, and rifampicin. Multidrug resistance was observed in 21% of newly diagnosed cases and 44.4% of relapse cases. “This is the highest rate of resistance ever reported for this bacterium,” says Mira, a coauthor of the paper published in July in Clinical Infectious Diseases. “This shows that the true extent of the problem is, to a great degree, unknown.”

Mira believes “the data should be viewed with caution, however, as residents in Vila do Prata have been exposed to leprosy for nearly 100 years.” Built in the early twentieth century, the leprosy colony is one of the oldest in Pará and was used as part of a compulsory isolation policy adopted in 1924 in Brazil to curb the spread of the disease. As many as 13,000 people infected with disease were treated in the village.

After forceful isolation was abolished in 1962, many continued to live there because of the stigma surrounding the disease. “Besides living in isolation, local residents have undergone nearly all of the treatment protocols available for leprosy over the years,” says Mira. “And yet they continue to become reinfected and transmit the disease-causing bacillus.” The researchers are concerned that what they observed in this region could be recurrent in other regions of Brazil where leper colonies were once located.

Scientific articles

ROSA, P. S. et al. Emergence and transmission of drug/multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium leprae in a former leprosy colony in the Brazilian Amazon. Clinical Infectious Diseases. July 2019.

CAMBAU, E. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in leprosy: Results of the first prospective open survey conducted by a WHO surveillance network for the period 2009-15. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. Vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 1305–10. Dec. 2018.