April 2, 1832, had already come and gone when the HMS (His Majesty’s Ship) Beagle entered Guanabara Bay. British captain Robert FitzRoy (1805–1865) refused to dock, preferring to wait until dawn. “We stayed anchored last night because the captain said we should see the Port of Rio and be seen in broad daylight. The view is magnificent,” said crew member Charles Robert Darwin (1809–1882) in a letter to his sister Caroline.

The 23-year-old Englishman, invited to take part in an expedition due to his interest in natural history, was fascinated by the tropical landscape that FitzRoy was eager to appreciate in the early morning light—and in which he planned to immerse himself. The expedition leader already knew just how striking the landscapes could be in the country that had recently been emancipated from Portugal. In 1832, he docked in Salvador, the Beagle’s first stop in Brazil after a long ocean crossing. There, he admired “every tint of green, enlivened by bright sunshine, and contrasted by deep shadow: and the general charm was heightened by turretted churches and convents, whose white walls appeared above the waving palm trees,” as he wrote in his account of the trip.

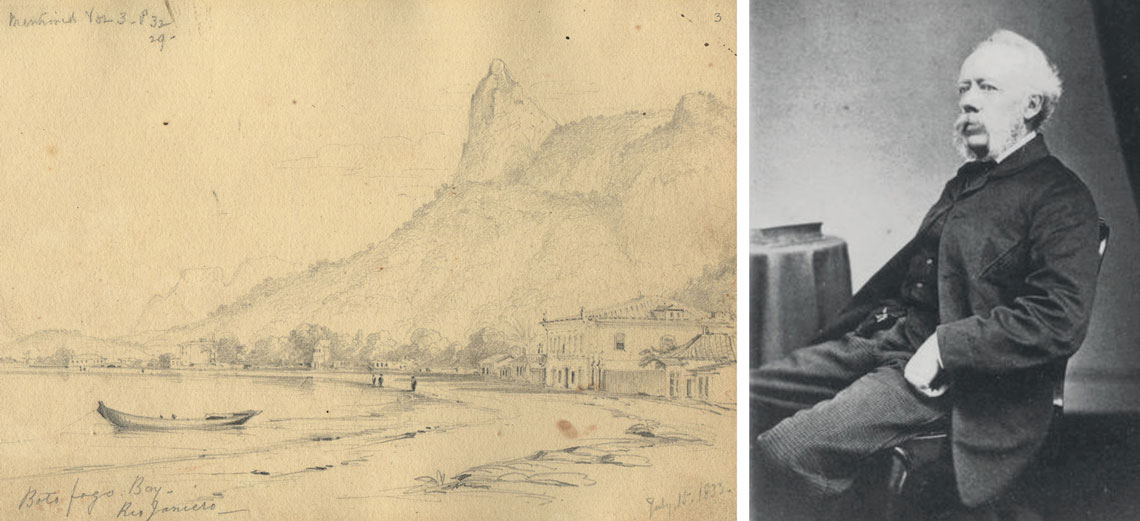

University of Cambridge | National Library of AustraliaBotafogo bay, watercolor by Conrad Martens (to the right), circa 1830University of Cambridge | National Library of Australia

FitzRoy had no intention of confining these scenes to his memory or travel journals. To join the circumnavigation expedition that took place between 1831 and 1836, he hired an artist: the experienced traveler and talented English painter Augustus Earle (1793–1838). But Earle fell ill during the Beagle’s passage by Uruguay, in 1833. According to Darwin’s diary entries, he suffered from rheumatism (he would die 5 years later in England from asthma). In November of 1833, Englishman Conrad Martens (1801–1878) would climb aboard the Beagle to replace Earle.

According to Marcos Ferreira Josephino, biologist and historian at the Clélia Nanci Institute of Education, in Rio de Janeiro, and author of an article about the two artists published in the June edition of Filosofia e História da Biologia (Philosophy and history of biology), Martens left England, aboard the Hyacinth, in 1832, with the intention of embarking on a three-year circumnavigation journey via South America and India. When he arrived in Rio de Janeiro and heard the news that the Beagle had lost its official artist, he left straight for Montevideo to offer his services to Captain FitzRoy.

Martens was considered an excellent landscape artist, but not as adept at portraits as his predecessor. In a letter written to Darwin in October of 1833, when the naturalist was doing research on land while the ship was docked in Montevideo, FitzRoy broke the news of Earle’s impending replacement, commenting that Martens’s landscapes were “really good, although perhaps, in human forms, he was no match for Earle.”

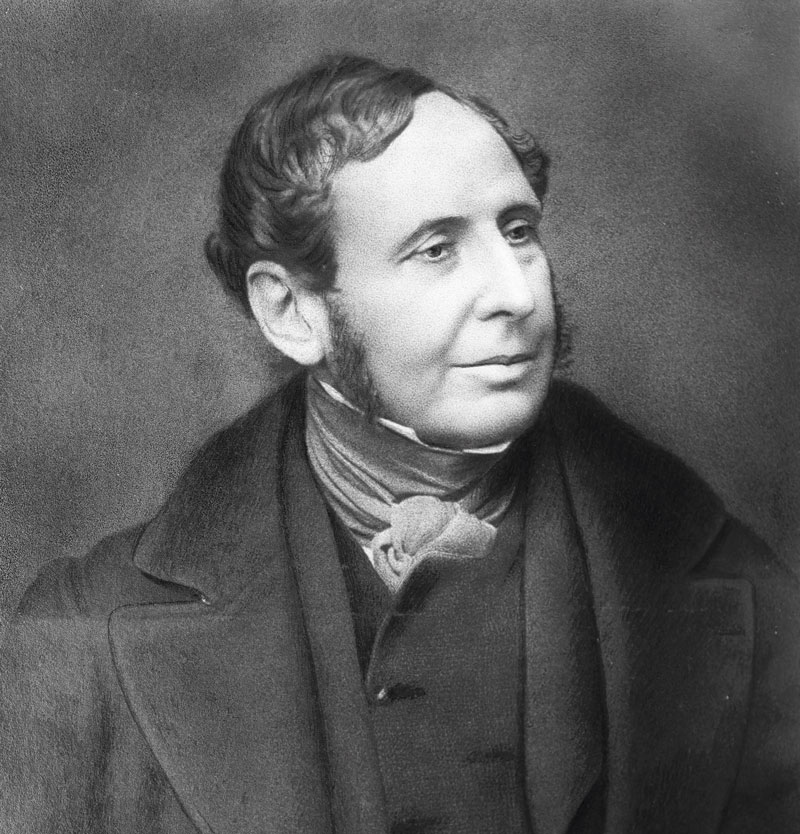

National Library of WellingtonCopy of the lithograph portrait of FitzRoy by Herman John Schmidt, circa 1910National Library of Wellington

Using mainly watercolor techniques, the artists depicted landscapes and scenes from everyday life in the countries they visited. “Watercolor, on account of it being portable, was the preferred technique par excellence. The travelers created small works of art, often in notebooks. “Some of these images were transferred to books using lithography,” explains art historian Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo (MAC-USP). One example of this is the lithograph by Thomas Abiel Prior (1809–1886) based on Earle’s illustration called San Salvador, Bahia and published in 1839 in FitzRoy’s book Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle.

The main objective of the Beagle’s voyage, commissioned by the British Royal Navy, was to perform a geographical and hydrographic survey of Tierra del Fuego and South America’s southern coastline, as well as to chart the circumnavigation route using marine chronometers (equipment used to determine longitudes). FitzRoy’s choice proved to be the right one for the purposes of this expedition. An exemplary student at the Naval Academy, he was known for his cartographic skills and scientific interests (when he retired from traveling, he became a pioneer in meteorological studies). According to an article by Gabriel Passetti, an international relations history professor at Fluminense Federal University, FitzRoy was so committed to the expedition’s success that he reached into his own pocket to purchase 17 chronometers, in addition to the five provided by the government, so as not to lose the correct bearings needed to define the meridians in relation to the Greenwich observatory.

National Maritime Museum in Greenwichwatercolor HMS Beagle off Fort Macquarie, Sydney harbour, by Owen Stanley, 1841National Maritime Museum in Greenwich

During this period, the British Royal Navy undertook several expeditions that linked scientific interests with commercial and political ones. The Beagle’s voyage could have blended in with so many others, now virtually forgotten, had it not been for the involvement of Darwin, a recent University of Cambridge graduate who would go on to become one of history’s most renowned scientists.

Josephino points out that the observations made during the expedition aboard the Beagle played an important role in developing Darwin’s theory of evolution, summarized in the book The Origin of Species, published in 1859. The naturalist’s accounts left a lasting mark on more than just fauna and flora. “Darwin fell in love with Brazil’s natural landscape but was shocked by the way enslaved Africans were treated to the point of writing in his diary that he hoped to never visit a slave country again,” he says. These dual impressions of the country can also be seen in the paintings produced by the artists aboard the Beagle—particularly Earle.

Wandering artist

Earle and Martens are little-known artists in Brazil. According to art historian Patrícia Meneses, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), there are two main reasons why these painters did not enjoy the same prominence in Brazil as their contemporaries such as Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768–1848) or German Johann Mortiz Rugendas (1802–1858). “The first reason is that although Darwin’s texts describe plant and animal species, they are not illustrated.” FitzRoy, who only publishes a few images in his book, mentions the recording of unknown fish species on the Beagle Voyage—”Mr. Earle made careful drawings of them, and Mr. Darwin preserved many in spirits”—but the drawings were not published. “The animal studies have been lost,” the historian laments. And of Martens’s work in Brazil, where the artist traveled before joining the Beagle expedition, only a few landscapes of Rio’s beaches remain.

University of CambridgeIslands off Rio harbour, by Conrad Martens, watercolor, 1833University of Cambridge

Another reason why these painters are rarely studied in Brazil is where their collections are located: the National Library of Australia. “The collections have been in Australia since the beginning of the twentieth century,” notes Meneses. Martens decided to raise his family in Australia, where he lived until his dying day. He settled there after leaving the Beagle in 1834 (after 9 months onboard, he was discharged due to lack of space) and traveling around Oceania. He is considered the country’s first professional artist. Earle also produced several works in Oceania, specifically in New Zealand and Australia, where he traveled between 1824 and 1828 and became famous as a painter of everyday scenes and portraits of important Australian figures.

Author of the book Augustus Earle (1793-1838): Pintor viajante (Travel artist; Novas Edições Acadêmicas, 2015), Guilherme Gonzaga, of the Higher Education Institute of Brasília (IESB), in Brasília, cites a third reason for the painter’s relative absence from the national academic landscape: the fact that he never collected and published his Brazilian images, as did Debret, Rugendas, and other naturalist or travel artists who were in Brazil in the nineteenth century. Having died at the age of 46, he never had a chance to do this.

Earle was, arguably, “the most widely traveled European artist in the first half of the nineteenth century,” states New Zealand historian Leonard Bell, professor of art history at the University of Auckland, in a 2014 article in the Journal of Historical Geography. He would become known by his contemporaries as the “wandering artist.” “Earle would become the first professional artist to visit all five continents,” adds Sarah Thomas, British professor of museology and art history at Birkbeck, University of London, in the Atlantic Studies, in 2011. The British painter spent over six years in the Americas, starting in 1818, four of which were spent in Brazil, from 1820 to 1824. His best-known Brazilian works come from this period.

National Library of AustraliaPunishing negroes at Cathabouco, Rio de Janeiro, 1822, Negroes fighting, Brazil, 1824, watercolor, by Augustus EarleNational Library of Australia

For Darwin, Earle’s participation in the early stages of the Beagle Voyage was providential. As he was familiar with Rio de Janeiro, he served as a guide as they traveled about the city. “They became friends and even shared a house in Botafogo,” highlights Gonzaga. It was Earle who brought Darwin to the top of Corcovado Mountain, which he had already visited during his first trip to Rio. “There is somewhat of an affinity between the artist’s image and the scientist’s description,” notes Meneses. In the watercolor View from the summit of the Cacavada [Corcovado] Mountains, near Rio de Janeiro, from 1822, Earle expresses his feelings toward the landscape in a very peculiar way, inserting himself into the scene, in a posture of amazement and wonder. The same admiration is expressed by Darwin in his logbook: “We soon gained the peak and beheld that view, which perhaps excepting those in Europe, is the most celebrated in the world. If we rank scenery according to the astonishment it produces, this most assuredly occupies the highest place.”

Brazilian scenery has been seducing European naturalists and artists since 1808, when the ports were opened to friendly nations, allowing several members of artistic and scientific expeditions to come to Brazil. In addition to landscapes, traveling artists depicted scenes from everyday life, such as work and leisure activities practiced by ordinary people—the so-called “genre paintings.” These representations of everyday life, however, cannot be considered faithful portrayals of reality, warns Magalhães, of USP: “There is nothing neutral about them. They construct the idea of a territory that needs to be civilized and will learn from the Europeans, because they are the ones with scientific knowledge.” Many of the engravings, oil paintings, and lithographs made during this period bear the idyllic image of a tropical paradise, in which slavery seems just another picturesque detail. But, according to Meneses, of UNICAMP, in some of these representations of everyday life, Earle seeks to go beyond the picturesque, taking a critical look at slavery. “Earle is more expressive and more attuned to social tensions than other artists of his time,” she says. She references the watercolor Negroes fighting, Brazil, of 1822, which portrays two slaves fighting. On the left side of the painting, you can see a soldier who, rather clumsily, tries to reach the fighters by jumping over a fence. At the time, capoeira was prohibited and continued to be considered a crime until 1937. “The artist not only recorded capoeira, but included the reaction it provoked, in a kind of social mapping,” says the historian. Bell compares Earle’s art to Darwin’s methods for scientific research: “Both are characterized by close and critical observation of natural phenomena and the people they encounter. Both of their practices went beyond accumulating factual information,” he wrote in an article about the painter.

Scientific articles

BELL, L. Not quite Darwin’s artist: The travel art of Augustus Earle. Journal of Historical Geography. Vol. 43. Jan. 2014.

JOSEPHINO, M. F. O Brasil de Darwin nas aquarelas de Augustus Earle e Conrad Martens. Filosofia e História da Biologia, Vol. 18, no. 1. June 28, 2023.

PASSETTI, Gabriel. O Brasil no relato de viagens do comandante Robert FitzRoy do HMS Beagle, 1828-1839. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos. Vol. 21, no. 3. June/Sept. 2014.

THOMAS, Sarah. On the spot: Travelling artists and abolitionism, 1770–1830. Atlantic Studies. Vol. 8, no. 2. June 2011.

Books

BELL, L. To see or not to see: Conflicting eyes in the travel art of Augustus Earle. In: CODELL, J. & MACLEOD, D. (eds.). Orientalism transposed: The impact of the colonies on British culture. Routledge. Abingdon, UK, 2018.

MARTINS, L. de L. O Rio de Janeiro dos viajantes: O olhar britânico (1800–1850). Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2001.