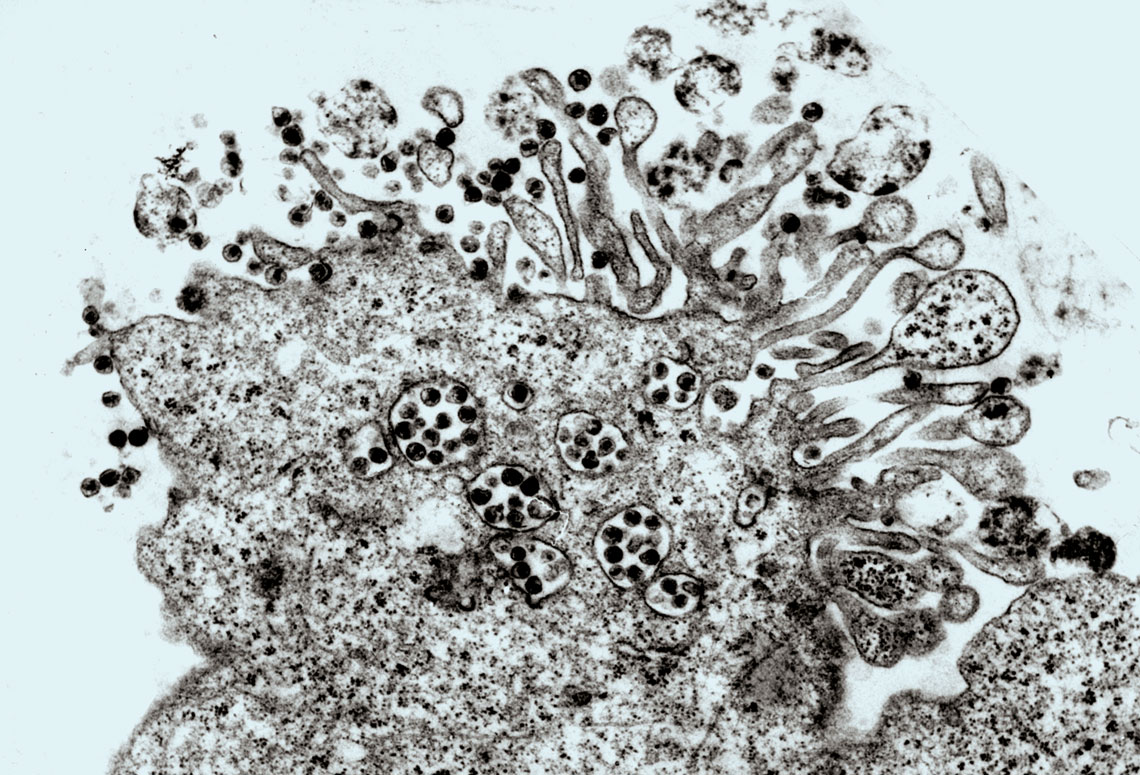

On a Friday, May 20, 1983, a team from the Pasteur Institute in Paris led by French virologist Luc Montagnier (1932–2022) published an article in Science announcing a discovery eagerly awaited by physicians and scientists: identification of the virus behind the new disease destroying the immune systems of patients, most of whom are young, leaving them vulnerable to opportunistic infections and rare types of cancer. Since 1982, the disease had been known as Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). In 1985, its causative agent was given the name Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

In addition to Montagnier, North American virologist Robert Gallo, who was also working to identify the new infectious agent at the University of Maryland’s Institute of Human Virology (IHV-UM), in the United States, claimed credit for the discovery. After several court battles, both scientists would be recognized as co-discoverers of the virus, with shared rights to the diagnostic testing patent. But it was Montagnier and his colleague Françoise Barré-Sinoussi who won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for this discovery.

In April of 1984, North American Health Secretary, Margaret Heckler (1931–2018), estimated that a vaccine for the virus would be ready in two years. Four decades later, this AIDS-fighting strategy still seems far off. “Vaccine development has proven to be a far more difficult task than we thought,” acknowledges infectious disease doctor Esper Kallás, director of the Butantan Institute, who has been researching ways to stop AIDS since 1996 at the University of São Paulo’s School of Medicine (FM-USP). “HIV has an immense capacity for mutation and, so far, it has managed to evade the immune response stimulated by experimental vaccines.”

Wikimedia Commons | NCIMontagnier and Barré-Sinoussi in 2008, receiving the Nobel Prize, and Gallo, co-discoverer of the AIDS virusWikimedia Commons | NCI

At first, doctors struggled to explain how cases of seriously debilitated patients were multiplying in the health services, many with severe pneumocystis pneumonia, which affects immunosuppressed people, or Kaposi sarcoma, a rare type of cancer that usually develops slowly in the elderly, but that progresses rapidly and aggressively in young AIDS patients.

“We used to enter the outpatient clinics wearing masks and special clothing to treat AIDS patients, just as we did recently with COVID-19,” recalls infectious disease doctor Rosa de Alencar Souza, assistant director of the STI/AIDS Reference and Training Center in São Paulo. During her medical residency, from 1986 to 1988, she treated many cases of AIDS, which had been spreading across the country since 1983. Facing a disease that was poorly understood taught her what she considers to be one of the most important lessons of her career: “Provide care, in the broadest sense.”

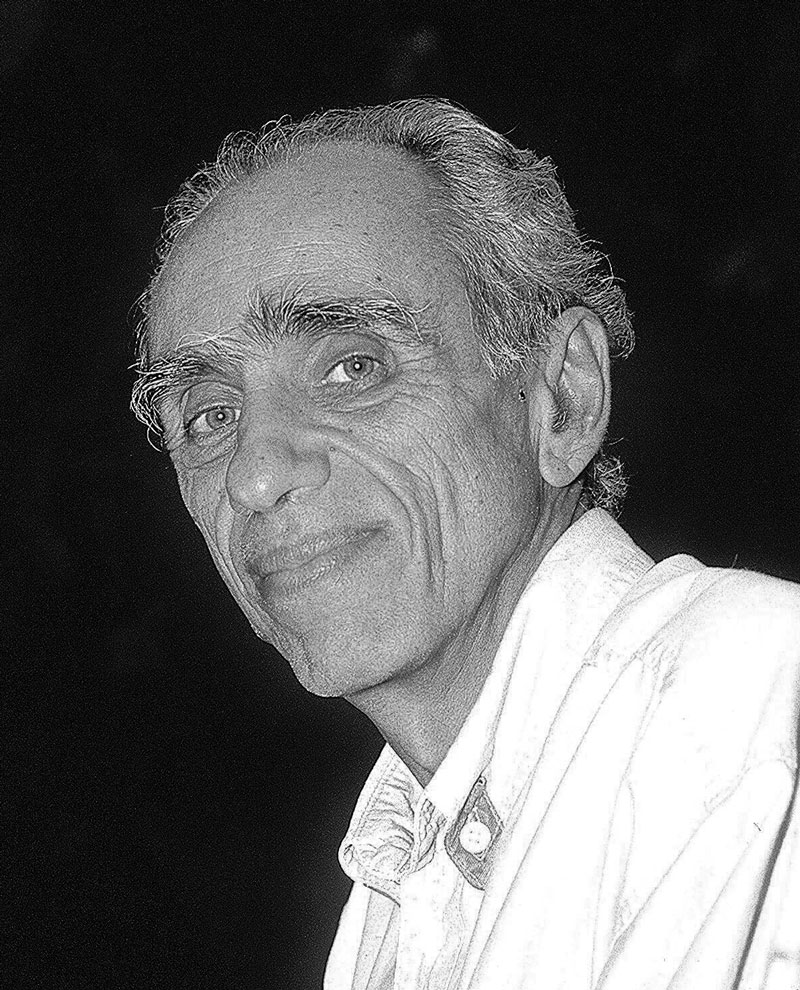

Genilton Vieira/IOCGalvão, coordinator of the group that isolated HIV-1 in BrazilGenilton Vieira/IOC

“In infectology, we often work with bacterial infections, which are generally cured with antibiotics, but as soon as I began my career, I was faced with a disease that had no cure and that could quickly lead to death,” Souza states. According to her, given the feeling of helplessness brought on by this scenario, medical care took on another dimension. In addition to treating opportunistic infections, the aim was to provide patients with more comfort and dignity. And within this model of comprehensive care, just one professional would not suffice. “We needed to work with other professionals from the mental health field, social sciences, and nursing. Multidisciplinary work became increasingly important,” explains the doctor.

Caring for a patient with AIDS symptoms also meant empathetically treating a twice victimized person suffering from the physical symptoms of the fatal disease, as well as the suffering caused by prejudice and marginalization. As the epidemic initially affected mainly homosexual men, it wasn’t long before prejudiced terms such as “gay plague” or “gay cancer” were disseminated by the media. Homosexuals continued to be seen as a “risk group” even after the disease began affecting heterosexual men and women and nonsexual routes of transmission were identified, such as through blood.

“At the time, ignorance was brutal,” recalled oncologist Drauzio Varella during a 2019 interview (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 279). The doctor witnessed the outbreak of the epidemic when he was in New York in 1983. Upon his return to São Paulo, he treated some of the very first patients with the disease and educated the population through radio and television programs. Currently, the expression “risk group” is no longer used, due to the discrimination it entails.

Rochelle Costi/FolhapressBetinho, advocate for policies to prevent the transmission of HIV through bloodRochelle Costi/Folhapress

Out of this suffering emerged a solidarity and mobilization between the homosexual population and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in defense of AIDS patients and HIV-positive individuals, who participated in developing a government plan to combat the epidemic. “Coordination with civil society was one of the hallmarks of Brazil’s response to the AIDS epidemic,” says public health director Maria Clara Gianna, one of the creators of the AIDS Reference and Treatment Center (CRT/AIDS) in 1988, who currently works in the Health and Environmental Surveillance Department at the Ministry of Health (MS). “The fight against AIDS has united NGOs, people living with HIV, doctors, and researchers. Several projects funded by FAPESP have boosted this response, enabling new technologies to be evaluated and incorporated,” highlights Gianna.

According to Artur Kalichman, a health worker with the CRT’s Epidemiological Surveillance Department since 1988, the fight against AIDS has three pillars: scientific evidence used to develop public prevention and treatment policies (as opposed to prejudiced and moralistic rhetoric); society’s reaction to discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS; and establishment of the Unified Health System (SUS), which devised the concept of health as “a universal right and a State duty,” expressed in the 1988 Constitution.

“Having an organized SUS made all the difference. COVID-19 demonstrated this once again,” says Kalichman. Through the SUS care network, condoms, medication, and HIV testing were made available to the public and changed the course of AIDS in Brazil.

Use of antiretroviral drugs began in 1987, shortly after the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved zidovudine (AZT). The treatment strategy was further consolidated in 1996 with a three-drug treatment option comprising two pills, improving the quality of life of those living with HIV.

Also in 1987, Brazilian immunologist Bernardo Galvão, an emeritus researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), isolated HIV for the first time in Latin America (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 118). From there, FIOCRUZ was able to produce testing kits, lowering costs and increasing access.

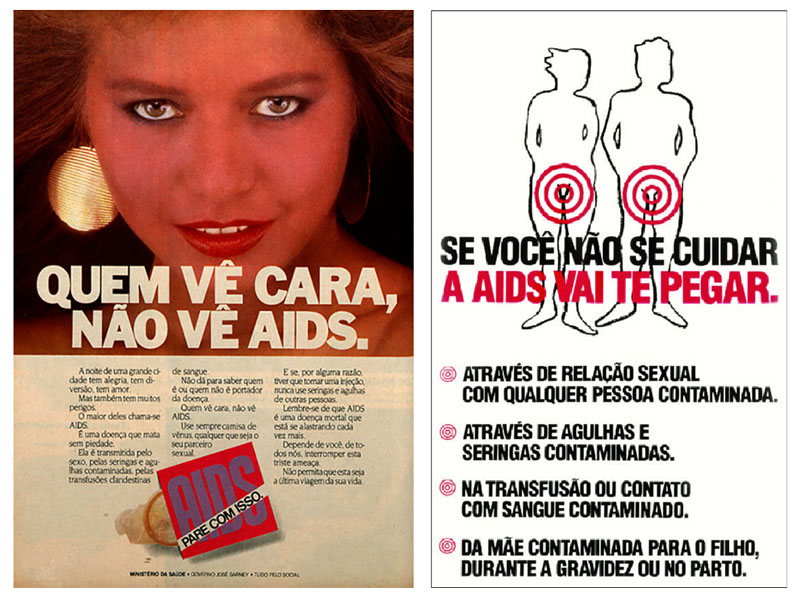

Biblioteca Nacional Digital/Agência Senado | Ministério da Saúde/Agência SenadoCampaign posters from 1988, with an image of a woman, criticized in the Constituent Assembly, and from 1990, with warnings about how the virus is transmittedBiblioteca Nacional Digital/Agência Senado | Ministério da Saúde/Agência Senado

The widespread availability of tests has helped protect blood centers, halting the rising rate of HIV transmission through blood transfusions. “The HIV/AIDS epidemic was pivotal for controlling blood-borne diseases in Brazil,” Galvão emphasizes. He explains that, in the 1980s, blood banks all over the country had no regulations or controls whatsoever: “To encourage donations, many offered money in exchange for donating blood, which attracted the homeless who were in poor health and often infected with HIV.”

Through Ordinance no. 1376, of 1993, the MS banned the sale of human blood and made screening for blood-borne infectious diseases compulsory. These guidelines were ratified eight years later, with the enactment of Law no. 10205, of March 21, 2001, which would be called the “Betinho Law,” in posthumous homage to sociologist Herbert de Souza (1935–1997) and his brothers — cartoonist Henfil (1944–1988) and musician Chico Mário (1948–1988) — all hemophiliacs who contracted HIV from blood transfusions. Betinho cofounded the Brazilian Interdisciplinary AIDS Association (ABIA), which he chaired until his death.

Law no. 9313, of 1996, was another milestone. “The law guaranteed that all people living with HIV would have free access to antiretroviral drugs through the SUS. To date, we haven’t had a shortage,” celebrates Gianna. In addition to people with AIDS, pregnant women have benefited, as they have access to medication that prevents the vertical transmission of HIV, that is, from mother to baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding. Women also receive formula to avoid transmitting the virus through their breast milk. “With these measures, we were able to eliminate vertical transmission in the city of São Paulo. The state of São Paulo is on the verge of achieving this. The goal is to have the entire country achieve this milestone by 2025.”

Treatment and prevention strategies, alongside mass media information campaigns, have enabled a continuous drop in AIDS cases within the country, from the peak of 43,850 reported cases in 2013 to 15,412 reported in 2022. This achievement is largely due to the physician Lair Guerra de Macedo, who founded the Ministry of Health’s National STD/AIDS Program, which she ran from 1985 to 1996, when she stepped down following a car accident.

Rovena Rosa/Agência BrasilCampaign promoted by the São Paulo State Health Department in the capital’s central region in 2016 for rapid HIV testingRovena Rosa/Agência Brasil

Developments in the fight against AIDS are not homogeneous. Epidemiologist Maria Amélia Veras, of the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, who has been studying the epidemic since the 1980s, when she worked in Recife, warns of an increase in cases of infection and death in states located in Brazil’s North and Northeast regions. “Overall, between 2011 and 2021 there was a drop in HIV detection rates across 16 states, but this rate continues to grow in 11 states,” she says. “As for AIDS deaths, the Ministry of Health recorded a 24.6% drop between 2011 and 2021 in most states, with the exception of Acre, Paraíba, Amazonas, Rondônia, Rio Grande do Norte, Piauí, Alagoas, Pará, and Mato Grosso do Sul.”

According to Kalichman, even the 15,412 registered cases of AIDS in 2022 — a 56.27% drop compared to the previous year, a possible effect of underreporting during the COVID-19 pandemic — needs to be viewed with a critical eye: “The occurrence of AIDS, currently, represents a failure in the health system. Once someone contracts HIV, it takes nearly eight years for symptoms to appear. That leaves enough time to receive a diagnosis, start treatment, and allow the patient to achieve an undetectable viral load,” he says. “The challenge is that some are being left behind due to their inability to access health services.”

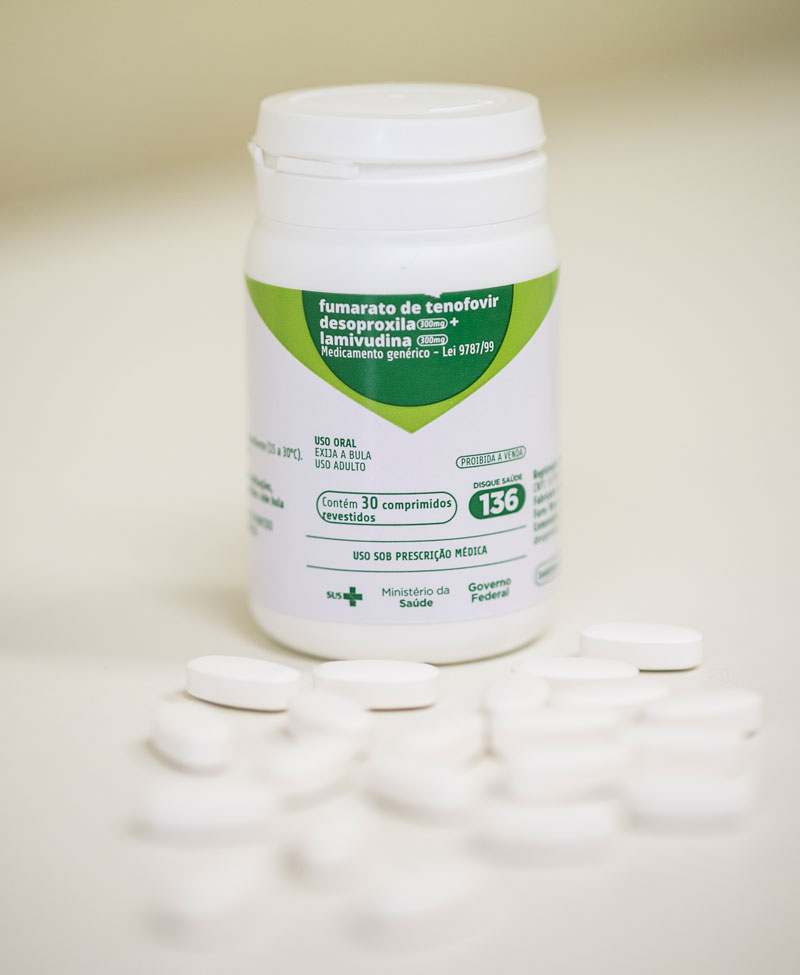

Eduardo Cesar/ Revista Pesquisa FAPESPTenofovir, one of the Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) medications, to prevent HIV transmissionEduardo Cesar/ Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Marginalized, Black, lower-income, and less educated populations are the most affected. Transgender men and women are at the extreme end of social and economic vulnerability. In the city of São Paulo, while the prevalence of HIV in the wider adult population is 0.4%, this rate can reach 40% for the above groups, according to a study conducted by the Nudhes research group (health, sexuality, and human rights for the LGBT+ population), coordinated by Veras. According to Veras, transgender men and women are the target of a confluence of stigmas based on gender, race, and social standing. Living in extreme marginalization, they struggle to access public health services and effective resources for preventing the disease, such as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).

Available through the SUS since 2018, PrEP consists of the daily use of an antiretroviral drug to prevent HIV from reproducing in the body, should the person come into contact with the virus. According to Kallás, this strategy prevents 99% of new infections. PrEP is intended primarily for people who are particularly vulnerable to HIV but has been most commonly used by white cisgender people with high levels of education. “In March of 2023, there were 23,302 PrEP users in the city of São Paulo, but only 3.9% were transgender men or women,” notes Veras.

AIDS has shown that social inclusion and equality are as critical as medication. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2022, 39 million people are living with HIV, mainly in poor countries. Although the AIDS mortality rate has fallen 55% among women and 47% among men since 2010, in 2022, AIDS-related diseases were the cause of death for 630,000 people. Worldwide, HIV remains a serious public health issue.

Brazil will have to intensify its efforts within the underserved populations if it wants to reach the “95-95-95” goal, established by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) for 2030 — diagnose 95% of HIV-positive people, treat 95% of them with antiretroviral drugs, and achieve an undetectable viral load in 95% of those undergoing treatment. So far, it has reached 88-83-95, respectively. “AIDS treatment has developed quite quickly, in terms of technology,” notes Kalichman. “Now, disease control is no longer a question of technology, but of citizenship and respect for human rights.”

Republish