A study published in June by researchers from the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA) estimated that growth in 2021 would exceed 200% in the resources available in the National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT), the federal government’s primary funding body for science, after approving a law that prohibits the use of the funds to create a primary surplus. This increase was postponed due to government action, which only overturned vetoes to the new legislation two days after the approval of the 2021 budget, but it is expected for 2022.

One of the authors of the study, economist André Tortato Rauen, elaborated on budgetary law under discussion in Congress and stated that the key resources from FNDCT are expected in 2022—approximately R$ 8.6 billion. But he foresees obstacles that could interfere with the distribution of the funds. One challenge is related to the schedule for disbursement—if the government does not release the funds until the end of the year, this could make the efficient use of the funds unviable. Rauen also believes there is a lack of bold projects to take advantage of the growth in funding.

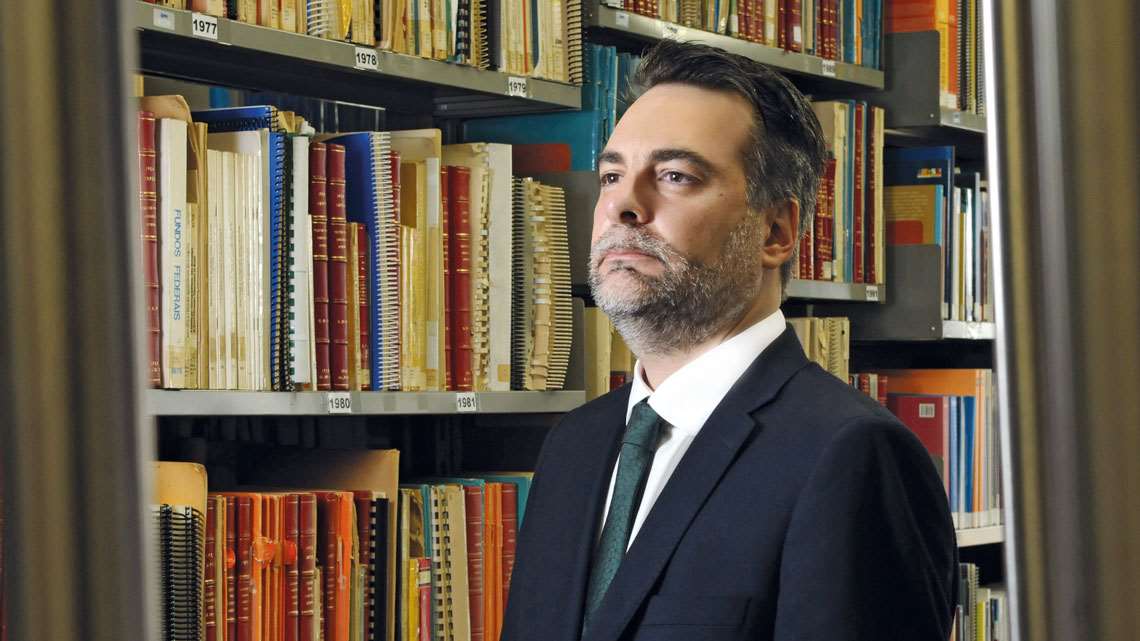

With an undergraduate degree from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, a master’s and PhD in political science and technology from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and a postdoctoral internship at Columbia University in New York, Rauen has been chair of the IPEA Board for Sectoral Studies and Innovation since 2019. In the following interview, he talks about funding perspectives for science and states that investment should be less diluted and should, in addition to basic research, be considered a solution to society’s greatest problems.

What can we expect regarding available funding from FNDCT in 2022?

As far as I could tell from the Annual Draft Budget (PLOA) that is being discussed in Congress and should be voted on at the beginning of the year, the expectations are positive. The budget for science and technology (S&T) is composed of an organic part, which is the usual budget that could be cut by Congress. And there is another part, the FNDCT, which can no longer be a contingency. PLOA will have 100% funding from FNDCT and the organic part will remain the same as previous years. If it remains as it is today, we will have something close to R$12.7 billion for S&T, the highest amount in many years. This is in line with the predicted funding we included in the technical note distributed in June. The amount expected from FNDCT is close to R$ 8.6 billion. In theory, the situation is very good, but we must remain attentive to some barriers.

What are they?

The possibility that Congress could cut the organic part of the budget and use the fund’s resources to pay for it. Furthermore, we must look at what will happen with the financial commitment and how the funds will be distributed throughout the year. If they are withheld and only released at the end of the year, this will make it difficult to be put to good use in an efficient manner.

If the budget actually increases, what will be the impact?

I was shocked at the lack of bold projects coming from the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) to make use of these funds. An initial study of the PLOA shows that there is only one new large project, the construction of a level 4 biosecurity laboratory—the first in Brazil—with an expected cost of R$200 million. Let’s assume that the PLOA delivers on this and that they approve a budget of R$12.7 billion. In the official documents, I cannot predict how this theoretically positive situation could be used to solve the big problems of Brazilian society. The funds could end up being too dispersed to have an impact.

If the resources of FNDCT are withheld and only released at the end of the year, it will be difficult to apply them in an efficient manner

Is it not necessary to restore investment in basic research and funding bodies that have been blocked in recent years?

Yes, and this is what has been the expectation. A large part of the budget is expected to cover management contracts for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The budget line item “Activities and maintenance of management contract with Nongovernmental Organization” is expected to increase from R$200 million in 2021 to R$805 million in 2022. The new level 4 laboratory will be one of these NGOs. There is also funding to complete the Sirius synchrotron light source. In 2021, Sirius received R$30 million. In 2022, it may receive R$221 million. Adding up everything assigned to NGOs—Sirius, the new laboratory, and older NGOs—it comes to R$1.2 billion. The grant from the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) is also expected to increase significantly—nonrefundable resources for innovation in business will likely double from R$350 million in 2021 to R$700 million in 2022, according to the PLOA. But we do not yet know how the funds will be applied nor what the metrics will be. The challenge will be to execute in an organized, coherent manner. There is one more aspect: in this post-pandemic reality everyone is still very confused. How can we invest in a coherent manner at a time when companies are restructuring, global chains are broken, variants of the virus are appearing, and uncertainties continue? Demand is not lacking, but have institutions prepared for this increase in budget execution? The PLOA has some more discretionary activities, such as funding research and development in basic and strategic areas. One operation grew from R$100 million to R$500 million. What is its mission? Who will execute it?

The Sectoral Funds for Science and Technology, the source of FNDCT funding, initially released requests for proposals (RFPs) for research projects of interest in the respective sectors of the economy. Should this be restored and end contingency funding?

Historically, the governance of the Sectoral Funds determined that, when resources were retracted from the electrical energy sector, for example, a committee of industry representatives would define the lines of research to which the money would be directed. As such, they raised significant sums and these committees became very powerful. Prior administrations of the MCTI then created the famous cross-sectoral initiatives. The administration became weaker and the ministry ended up defining the direction of the sectoral funds, flooding the entire system with FNDCT funding. The governance issue remains.

Has the PLOA said anything about this?

The more cross-sectoral initiatives are much larger than the sectoral ones. But the resources destined for sectoral execution must increase. The agrobusiness sectoral fund—CT-Agro—for example, had very little money in 2021: there was R$336,000 available. In 2022, it is expected to be R$70 million. They are increasing the funds, but it is still very little next to the R$466 million provided to the cross-sectoral initiatives that fund institutional projects. It is necessary to revisit the governance of the Sectoral Funds to increase the output for society.

How is the situation with the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)?

A restructuring of the grants is expected, in line with this general improvement, and the budget is expected to reach close to R$1.3 billion. Here the challenge of the actual disbursement is very relevant since the funds must be released in a constant manner throughout the year, with the risk of having grants canceled. With respect to CNPq, we were also made aware of the absence of recent data on grants awarded. The most recent data available are from 2015. Surely this problem is related to the increased number of retired technicians and the virtual nonreplacement of personnel, affecting the entire public system for innovation.

Is there risk involved in releasing funds in the form of credit to businesses, rather than nonrefundable resources for innovation, as was done in 2021?

Grants will increase substantially—to R$700 million—but credit to companies will continue to be significantly higher. They will grow from R$3.6 billion to R$4.2 billion. Thanks to a very low tax rate for business innovation, an adequate and continuous volume of credit is very important. I believe this to be a positive point—the overall question is what we want with this. I would say, in terms of a solution for our historical challenges, such as low economic productivity.

Another study by IPEA, in which you participated, noted how the new National Strategy for Innovation, which was presented by the government in July, was classified as excessively broad. Does this strengthened case not help reach those goals?

We have there a set of intentions but very little that is concrete. But this is not due to the exclusivity of this strategy or of the federal management. Whenever a document like this is released, the problem repeats. All existing intentions in the system of innovation appear together, without selecting or prioritizing anything. What we expect from one effective strategy is that it makes choices. The United States designed a concrete objective in their policy of innovation: they want to recover their power in manufacturing and return to being competitive with China. Germany wants to develop green technology. Europe, as a whole, wants to develop technologies to support its aging population. Clearly there are other goals, but there is a central logic, a drive. Our strategy does not make any choices. The ideal scenario would be to discuss these choices with academics and with businesses. IPEA conducted such a discussion recently and suggested that the Brazilian drive should be to look for solutions for social problems and to increase the productivity of the economy. Some top priority topics in S&T were raised, such as security, mobility, access to water, and the environment. When choices are not made, the strategy becomes a letter of intentions in which everyone can view it but where it does not help with the execution of a public policy for innovation based on mission.

It is surprising we do not have a basic design to create a vaccine against dengue, zika, and chikungunya

There are goals linked to companies, which are very ambitious, such as increasing the rate of innovation from the current 33% to 50% by 2024. But the goals associated with government action are more conservative. Is it worth establishing goals that are difficult to reach?

We must have these goals. They were bolder in the 50% innovation rate. I think the concern for a new strategy to improve the business environment is interesting—a topic that is highly supported by the current administration. There is a recognition that money addresses part of the problem, but not all of it. But what is more concerning about this goal is the absence of a basic plan to achieve it. Brazil is a country the size of a continent, technologically dependent, and with a massive number of socioeconomic and environmental problems. The strange part of this strategy is that a very bold objective has been put forward without an equally bold action plan to reach it. Large, complex problems require complex solutions for both the medium and long term.

What would you suggest?

First, to guarantee solid and continuous funding for basic science, which is guided by curiosity and without which the S&T system would not function. Second, to select concrete problems that can be addressed by science. This breaks the pattern of choosing technological areas or segments of the economy to benefit—the focus is the solution to the problems. This is what the Americans taught us with the Warp Speed project to accelerate the development of vaccines against Covid-19. The government assigned resources where there was the greatest potential for innovation and was able to obtain a clear deliverable. In Brazil, this is the perfect time to do this because there is new money. That is, we will not take away from basic science to invest in solving problems related to Brazilian challenges.

What topics could inspire a Warp Speed project here?

It is surprising that we have not yet developed a basic design for a triple vaccine against dengue, chikungunya, and zika. How do we not yet have a science, technology, and innovation (ST&I) program to solve urban mobility problems, which threaten the lives of Brazilians and their productivity? Many of the country’s challenges have nothing to do with ST&I, such as the question of income distribution. But others have everything to do with it, such as seeds that can adjust to climate change or the efficient industrial application of 5G. We support a funding logic that focuses on concrete missions and we are bold in this investment. The central idea is to substitute the sectoral support paradigm for support for clear deliverables that resolve concrete problems. Such as what happened with the Sirius project and that of the Brazilian Multipurpose Reactor.

But the multipurpose reactor project is on hold…

It was given very little budget to work with. The reactor is just as important as Sirius. Dominating the production of radiopharmaceuticals is fundamental because the Unified Health System (SUS) consumes much of these inputs. Today we prefer to widely distribute the resources to ensure the maximum number of institutions and researchers receive some support. This guarantees curiosity-driven research incentives, which is the foundation of any innovation system. But it is also important to ensure that a portion of the resources be focused on large projects and national problems. The funding instruments directed to these large projects are more difficult to execute. They are demand-driven and, therefore, the technological order must be defined. We know how to do this. We did this with Sirius. The world abandoned this system that distributes money by sector and moved to moonshots. One of our moonshots, in my opinion, should be a triple vaccine.

You are a specialist in technology commissioning, and you participated in developing legislation for this in Brazil. Have there been any advances?

I am biased. But look at the context: we are in an extremely polarized country that always connects public purchasing with corruption. Then something appeared called technology commissioning, which inverts the logic of public purchasing and says: look, you may fail, you may contract more than one supplier, you may negotiate strategies with suppliers. We did not expect the orders to take off, but great things have begun to happen. A commissioned technology is helping us to overcome the pandemic. If it were not for this instrument, FIOCRUZ would not have purchased the AstraZeneca vaccine. We bought the vaccine on a chance. The vaccine did not yet exist. If we had not placed this order, we would have had to wait to buy it after it was ready and go to the end of the line. The instrument allowed us to access the technology before it was ready.

Do you have other examples?

Another example is when the Federal Supreme Court commissioned a decision-making algorithm. And the Navy, a Blue Amazon security system. Even municipalities are using the instrument. There is also something new that arrived recently from the Marco Legal das Startups, called Public Purchasing for Innovative Solutions. As an example, a distribution department has a problem to solve and knows there could be different solutions. There are various startups offering different solutions. It would not work to put out an RFP based on lowest price because this would not be effective: in practice, there would be no information about what each solution offers. Therefore, you would put out an RFP to select based on performance determined via testing. Microsoft bids, a startup bids, my startup bids, everyone competes with their own solution. And you are compensated during the test. A Public Contract for Innovative Solutions has in its DNA these elements we have supported, where the problem defines the development of innovation.