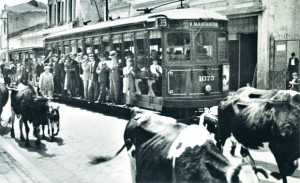

Reproduction The uncomfortable coexistence of the modernity of the streetcar and the ancientness of the ox in the capital cityReproduction

According to records, it was back in 1685 in Recife when a mosquito bit an unsuspecting citizen, thus leading, apparently, to the first case of dengue fever in Brazil. Today, more than 300 years later, well into the twenty-first century, a simple mosquito can still subjugate a country, a sign that Brazilian modernity was unable, as those who were firm believers in progress believed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, to “overcome” the “backwardness” represented by “animals”. Even in an advanced metropolis such as São Paulo. “In that period, the city’s animals went through a process of ‘recolonization’, part of the process of transition from a pattern based on colonial roots to another, that included elements of modernity, in which men redefined their attitudes and relations with animals, by opposing ‘leather’, an animal symbol, to ‘steel’, the modern element,” says Nelson Aprobato Filho in his PhD thesis, Leather and steel: the “adventure” of animals through the “gardens” of São Paulo city, defended at the history department of USP , under the guidance of Nicholas Sevcenko, with FAPESP support.

“My goal was to understand the effects of modernization on the city’s animals and show that the modernization of São Paulo took place in its dimensions (real, imaginary or symbolic) thanks to and by means of animals and the attitudes, practices and sensibilities that man started to embrace concerning them,” he adds. According to the researcher, with the scientific and technological revolution, animals acquired unexpected importance, given that in the development of large cities, animals were, for humans, the constituent part of a “culture of ongoing and stable references,” which, according to the researcher, progress dilapidated. “Therefore, the physical and symbolic choice of animals was symptomatic. They were the singular elements of experimentation, comparison and contrast for the justification or detraction (real or imagined) of modernity in São Paulo.” Examples abound, from “Either São Paulo does away with the leaf-cutting ants, or these ants will do away with São Paulo” to the association, made by writer Monteiro Lobato, between the national social framework and the ox cart, regarded as something pernicious and a symbol of backwardness, of slowness, and of “old” rusticity. Not without reason, a comparative statistical analysis conducted in São Paulo of the number of cattle, horses, asses and mules shows that in 1905 they numbered 21,606; by 1920, they had risen to 38, 885, but by 1940 they were down to a meager 5,375. Within two decades, more than 35,000 animals disappeared from the landscape of the big city and, more importantly, from the awareness of its citizens.

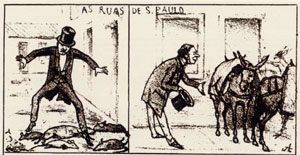

This process of “depreciation” started back in the mid-nineteenth century. “Just look at the caricatures of Angelo Agostini in Cabrião or in Diabo Coxo, to see how, at that time, animals were increasingly associated with backwardness, apathy and filth. However, according to the sociocultural reality of the time, the flexibility of leather was even hardier than the consistency of steel. Gradually this situation was reversed,” explains the author. At that time, it was not hard to spot 300 ox carts (which would only disappear between 1910 and 1920) while moving between São Paulo and Santo Amaro. The city was constantly crossed by herds of 40 to 80 animals. “If by chance herds ran into each other in a São Paulo street, one could see the traffic caused by 320 mules and the hundreds of insects and parasites that accompanied these herds. From these to ox carts, from horse-drawn carts to riding horses, from droves to vultures, from birds to fish, and so on, animals existed; they invaded the streets, squares and plazas. It was quite impossible not to coexist with them,” he says. The counterpoint to such everyday living, in which animals were, in a fairly balanced manner, the agents and patients, manifested itself in the projects and mechanisms created by elements linked to the government, to the scientific and technological entities that came into action in São Paulo as from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Reproduction Visions of the unsuitability of animals in São Paulo, in the view of AgostiniReproduction

“By tracking the various laws and projects targeting the animals, one sees how the government dealt with the issue: what would be their places, functions and roles in the new city; which animals would be ‘elected’ to remain in the urban milieu; and what were the clashes between the animals and progress.” The researcher notes that this was also the time when the tendency to view engineers as the professionals most qualified to manage the destiny of a city arose. “They start to cast a greedy look upon the municipal administrations that subordinated its people and animals to the mechanisms of modern engineering. Between leather and steel, a new and exclusive technological mentality was sprouting up. On the trail of the mules, which for them were synonymous with the countryside and a colonial past, the São Paulo engineers tried to underpin their ideals of civilization on a ‘crusade’ for modernization,” he notes. Even unexpected victims, such as dogs, became the target of campaigns of repression by regulatory laws that included having the city government spend money on “balls of food with poison inside”, given to the dogs that were loose on the streets, as well as fees and the mandatory use of collars (“dogs must be muzzled and wear a numbered collar indicating that the city tax has been paid”, stated Law no. 68 of the Code of Postures, 1886). There were heated discussions about what was or was not a “dog of breeding” and therefore subject to privileges. “To build a modern city one had to create mechanisms to correct the tendency to one that denoted ‘vagrancy’, whether of men or of dogs.”

Tingling

not only mongrels acquired a metaphysical connotation. “The war against ants mobilized the city at all levels, both in the physical destruction of nests, and through its symbology. Lobato was one of the writers from São Paulo that most used the insect as a symbol of archaism and ruralness. This accompanied his thoughts for decades. In his caustic thesis, written in 1908, for example, ants represented the antithesis of progress, a clear demonstration of the backwardness in which the cities were submerged, along with the poor.” Twenty years later, Andrade was to talk about them in a more ironic tone in Macunaíma. “There is still so much left, in this great country, in terms of diseases and insects to be taken care of. We are corroded by morbidity and myriapods. We will soon be a colony of Britain or North America. For this reason and for the recollection of the people of São Paulo, the only useful people in the country, we propose a couplet: ‘Not enough health and too many ants, these are the evils of Brazil’.” Historian Nicholas Sevcenko, in his article “Brazil and the ants” sums up in a curious way the metaphorical use of the “bothersome insect” by the various ruling elites, at different historical periods, whenever an attempt was made to “eliminate the leaf-cutting ants”, whoever they might be: the agrarian elite of the twentieth century and Jeca Tatu; Vargas and the campaign against rogues; or the military and the repression.

The animals, however, might have been an ingrained habit that was difficult to contain. “If we consider the various laws, for example, we see the inefficiency of the government measures that attempted to curb the ox cart traffic through the center of capital. One notices, particularly after 1900, the insistence of the government in keeping such elements away from the ‘better areas’, as well as the resistance of the ox cart drivers to abandon a form of transport that had everything to do with popular forms of survival. These figures and their animals would become undesirable and dissonant visions in the new metropolis.” At the same time, the leather and steel, in the face of nascent technology, were forced to coexist, as in the case of streetcars pulled by animals. “Given that hitherto animals had been seen in herds of mules or pulling carts, the population found this strange, being unaccustomed to this kind of driving. For the animals it was equally strange, as the weight of the streetcars was much greater than they were accustomed to.” In the words an eyewitness, “Groups climbed on and off the streetcars and stopped in front of the poor mules, which, under the ardor of whips, did the impossible: pulled those streetcars whose weight was well over the top.” There were those who complained about the new service because they suddenly found themselves living next door to the stables. “Is there no way to do away with such an uncomfortable gathering?” one resident of the Rosário area complained to the authorities.

Reproduction Progress was soon to bring peace to the troubled. From 1901 onward, the monopoly of urban transport came under the control of a Canadian firm, Light & Power, which began to withdraw streetcars pulled by animals from the central streets of São Paulo. The last one was removed in 1910. From its initial enthusiasm for the new form of transport, the city was now ashamed to have to ride mule-drawn streetcars. “There was the Santana revolution, organized by the residents of this district, who, unhappy to belong to one of the few neighborhoods in the city still served by animal-drawn streetcars, turned to force to intimidate the government and the Light & Power company. They released the donkeys and set fire to streetcars,” says Aprobato. At the same time, the electric streetcars did not affect only the ego of São Paulo inhabitants. “For a population accustomed to transport whose speed parameter was the speed of oxen, mules and horses, full adaptation to the new vehicle was underscored by constant fears and anxieties.” Zoologist Afonso Schmidt described how “conservative minds, accustomed to the sweetness of a streetcar pulled by a pair of lyrical mules did not look kindly upon their replacement by large, clean, fast, electric power driven vehicles. Craftily, they claimed a holy horror of disasters.” It became necessary for companies to hire “accident technicians”, people who let themselves be run over by streetcars at a speed of eight points to demonstrate the effectiveness of the rail clearers.

Reproduction Progress was soon to bring peace to the troubled. From 1901 onward, the monopoly of urban transport came under the control of a Canadian firm, Light & Power, which began to withdraw streetcars pulled by animals from the central streets of São Paulo. The last one was removed in 1910. From its initial enthusiasm for the new form of transport, the city was now ashamed to have to ride mule-drawn streetcars. “There was the Santana revolution, organized by the residents of this district, who, unhappy to belong to one of the few neighborhoods in the city still served by animal-drawn streetcars, turned to force to intimidate the government and the Light & Power company. They released the donkeys and set fire to streetcars,” says Aprobato. At the same time, the electric streetcars did not affect only the ego of São Paulo inhabitants. “For a population accustomed to transport whose speed parameter was the speed of oxen, mules and horses, full adaptation to the new vehicle was underscored by constant fears and anxieties.” Zoologist Afonso Schmidt described how “conservative minds, accustomed to the sweetness of a streetcar pulled by a pair of lyrical mules did not look kindly upon their replacement by large, clean, fast, electric power driven vehicles. Craftily, they claimed a holy horror of disasters.” It became necessary for companies to hire “accident technicians”, people who let themselves be run over by streetcars at a speed of eight points to demonstrate the effectiveness of the rail clearers.

Pace

“The electric streetcars, more so than their predecessors, the animal-drawn streetcars, for their technological uniqueness and their sensory and perception impact, were one of the main vehicles of urban behavioral and sociocultural transformation in São Paulo in the early twentieth century,” notes the researcher. He adds that they “awakened the city’s inhabitants to a new pace that they would be obliged to keep up with thereafter.” However, this was not enough. Joseph Agudo, in Gente rica – Scenas da vida paulistana, reveals the new desires through the character of Dr. Zezinho, “nattily dressed and a frequenter of casinos and boarding houses that have no closing time.” For him, it was hell to get home “after two in the morning and not be able to sleep because the noisy streetcars and carts had started.” After all, cars were coming into being and soon “every nobody will have his own.” “They also leave behind them a terrible stench of gasoline, but it’s chic to go by car. Oh! A 40 HP is superb. Later, anyone who rode in it is neither covered in dust nor does he smell the stench of the exhaust. Those who went on foot can jolly well lump it, now this is really a fine state of affairs!,” philosophized the São Paulo playboy, for whom the city should have “paved the streets with rubber.”

Dr. Zezinho also embraced other philosophies. “Streetcars came into being to make things easier for the donkeys. Now one can be a donkey in São Paulo, because for them there are water fountains in public squares. Right there in Largo São Francisco square there is one. Isn´t this a wise measure. How many donkeys suffered from thirst before. If donkeys could talk, one of them, which perhaps came here to sightsee, parodying the famous Sarah Bernhardt, might cry out: ‘São Paulo is donkey paradise!'” Leather and steel started an estrangement whose ultimate effects we are still feeling to this day.

Republish