ReproductionThe best way of dealing with genetic diseases for which there is currently no cure, such as muscular dystrophy, may be found within the patients themselves. This is what the work of Patricia Arashiro, from the University of São Paulo (USP) suggests. To be published in the journal PNAS, it has identified differences between the activity of the genes of dystrophy patients and of people who have the genetic modifications but do not develop the disease. For geneticist Mayana Zats, the study’s coordinator, the results show that not everything is about stem cells, where the quest for therapies is concerned. Up to now, all hopes had focused on those cells that can generate range of tissues.

ReproductionThe best way of dealing with genetic diseases for which there is currently no cure, such as muscular dystrophy, may be found within the patients themselves. This is what the work of Patricia Arashiro, from the University of São Paulo (USP) suggests. To be published in the journal PNAS, it has identified differences between the activity of the genes of dystrophy patients and of people who have the genetic modifications but do not develop the disease. For geneticist Mayana Zats, the study’s coordinator, the results show that not everything is about stem cells, where the quest for therapies is concerned. Up to now, all hopes had focused on those cells that can generate range of tissues.

Patricia studies Facio-scapulo-humeral dystrophy (FSH), which affects one out of every 20 thousand people in the world’s Caucasian population and that first manifests itself as a weakness in the face muscles that makes it difficult to purse one’s lips and close one’s eyes. The disease then advances to the muscles of the shoulders, abdomen, arms and hips. In some cases the patient may end up in a wheel chair; the symptoms may be accompanied by depression, muscular pains and tiredness. What is striking about this illness is that the patient’s set of clinical symptoms are highly variable, to the point that there are symptom-free patients, even though they have the same genetic defect. Therein lies the mystery: what protects some people from the damaging effects of genetic alterations? “We had nothing that could explain variation”, Patricia tells us.

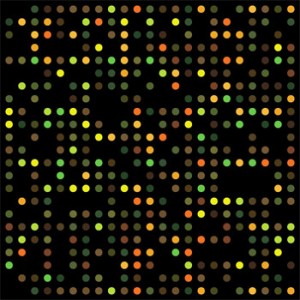

In order to understand where these differences stem from in the manifestations of dystrophy, one of the lines of research of the Human Genome Studies Center – which is one of the 11 Cepids (Centers for Research, Innovation and Dissemination) financed by FAPESP – Patricia collected muscular biopsies from five families that carry FSH dystrophy. In each, she selected one person without the mutation that causes the disease, another with the mutation but no symptoms, and a third one truly affected by the disease. From this material, she extracted the RNA, which indicates which genes are active in the sampled muscle. Because of the requirements of the FSH Research Society in the United States, which financed part of the work, Patricia analyzed the levels of expression of the genes of all of the 15 patients at the laboratory of geneticist Louis Kunkel at the Children’s Hospital of the University of Harvard, in the United States. In this analysis, the level of activity of the genes appears in different colors in an RNA chip, as represented at the top of this page.

Hidden variability

“Our study is the first in the world to compare the profile of gene expression among people with symptomatic and asymptomatic FSH”, states Patricia. She found a group of 11 genes that were more active among the symptom-free patients – genes that may somehow protect them from the manifestation of the disease. Three of them were striking: they were chemokines, i.e., proteins that normally help to recruit cells from the immune system for inflammation points. It was a surprise, as up to then no work had shown that chemokines were produced in larger amounts in any type of muscular dystrophy. The USP group is yet to figure out how these molecules might interfere with the disease’s symptoms. “We need to carry out further studies”, Patricia stresses and repeats.

Besides suggesting genes that are candidates for protecting those who bear the disease-causing mutation, the geneticist also found changes that may provide a lead for understanding how FSH progresses. The people with this type of dystrophy that were analyzed seem to have a deficient production of a type of molecule with a virtually unpronounceable name – glycosilphosphatidilinositol anchors – which bind with proteins as soon as they are produced within the cells and lead them to the cell membrane. “Perhaps this affects the signaling mechanisms between the cells”, explains Patricia. The results also indicate a possible alteration in the conformation of histones, essential proteins for bundling the genetic material within the cells. This finding suggests a strong source of changes in the expression of the genes, given that the way in which DNA is wound up has a direct effect on which parts are exposed to the mechanisms that translate genes into proteins. Finally, the study also showed that a larger quantity of small RNA molecules – the micro RNAs – seem to keep the genes that carry the dystrophy symptoms from functioning normally.

These results are far from being definitive answers, but they will form the basis for new studies that will try to understand how the body can offset these genetic defects and, perhaps, even point to treatment possibilities. Patricia and Mayana see a long path ahead of them, but believe they are going in a fairly promising direction.

Scientific article

ARASHIRO, P. et al. Transcriptional regulation differs in affected facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy patients compared to asymptomatic related carriers. PNAS. 2009