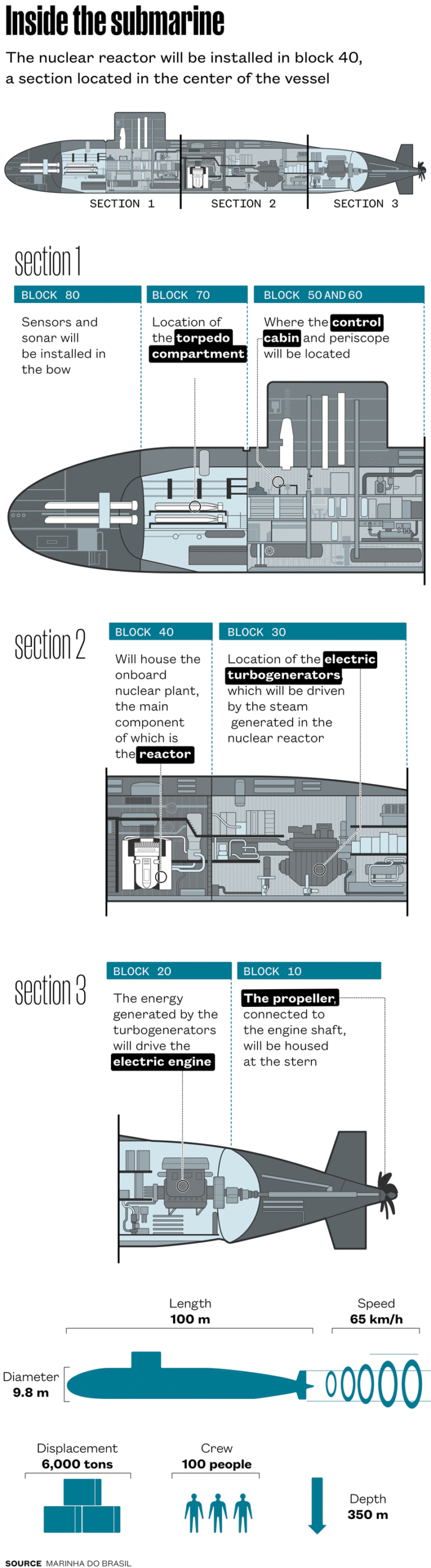

The Brazilian Navy is taking another step towards achieving its goal of adding a nuclear-powered submarine to its fleet. A crucial phase of the Brazilian project—the electromechanical assembly of the section called block 40, which will house the prototype reactor responsible for generating the thermal energy for propulsion—is at an advanced stage, according to the Naval Force. To test this equipment, a full-scale model of the submarine’s mid and rear sections, blocks 10 to 40, is nearing completion at one of the laboratories of the Aramar Nuclear Industrial Center (CINA). This military complex, dedicated to nuclear research and commonly referred to simply as Aramar, is located in Iperó, 115 kilometers from the city of São Paulo.

A research unit called the Nuclear Power Generation Laboratory (Labgene) was set up exclusively to test the nuclear reactor. Its main building, a large hangar, about 30 meters (m) high, is where the submarine prototype is being assembled. According to the Navy, the propulsion plant will initially be tested with steam from a conventional fossil-fuel boiler. Only afterwards will it be powered by nuclear fuel, also produced at Aramar.

The purpose of Labgene is to validate the operation of the naval propulsion reactor and its integrated electromechanical and control systems. The vessel will be built approximately 550 kilometers away, at the Itaguaí Naval Complex in Rio de Janeiro.

“The construction of an onboard nuclear plant is unprecedented in Brazil. We have never done it before. We will need to test it extensively before installing it on the submarine,” said Vice Admiral Celso Mizutani Koga, director of the Navy Technological Center in São Paulo (CTMSP), during a visit by FAPESP Research reporters to CINA in May this year. “We will have to ensure that all safety and performance requirements are met. We estimate that it will take three years for Labgene to begin producing energy through nuclear fission.”

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP A building in Aramar where uranium concentrate is converted into uranium hexafluoride gas, part of the nuclear fuel production processLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

The reactor designed by the Navy is a pressurized water reactor (PWR), the most commonly used model in nuclear power plants worldwide, including Brazil’s Angra 1 and 2 plants on the coast of Rio de Janeiro. The state-owned company Nuclebrás Equipamentos Pesados (NUCLEP), created in 1975 to serve the Brazilian Nuclear Program (PNB), is handling the development of the block 40 components.

“We are doing a lot from scratch because the countries with nuclear submarine manufacturing technology do not share it, which creates numerous challenges due to its novelty and the need for domestic development,” says Koga.

Despite the complexity and challenges involved in building a nuclear plant—whether on board a submarine or at a power station—it operates similarly to a thermoelectric generator: heat from burning fuel produces steam, which drives a turbine connected to a power generator.

In a nuclear generator, the steam is created not by the combustion of diesel oil or natural gas, but by the thermal energy released during the fission (splitting) of uranium atoms, the base mineral for nuclear energy. Heat conduction circuits containing heated water and steam drive the turbine that powers the electrical system’s generators, producing electricity. The advantage of nuclear energy over fossil fuels is its high energy density: one pellet of enriched uranium weighing just a few grams releases the same thermal energy as one ton of coal.

Secret military program

The construction of a conventionally armed nuclear submarine (the SNCA) using Brazilian technology is one of two objectives of the Navy’s Nuclear Program (PNM), one of the arms of the PNB. Now under the responsibility of the CTMSP, the program began in secrecy under the codename Chalana in 1979, during the military dictatorship (1964–1985). It was only made public after democracy was reestablished in the country.

Since then, the program has faced numerous challenges and budget constraints that have nearly resulted in it being shuttered and have forced its timeline to be repeatedly revised. Experts interviewed by Pesquisa FAPESP estimate that the vessel will only be ready by the middle or end of next decade.

Construction of the SNCA, named Álvaro Alberto (1889–1976) in honor of the scientist and Navy officer who helped create Brazil’s nuclear program, is also part of the Submarine Development Program (Prosub), a partnership between Brazil and France. The agreement includes the development of four conventional diesel-electric powered submarines (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 274).

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP A model of the submarine reactorLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

“Today, only six nations are capable of manufacturing nuclear submarines: the US, Russia, China, the UK, France, and India,” says Rear Admiral Sérgio Luís de Carvalho Miranda, the Navy’s director of nuclear development. “Brazil is the first country without nuclear weapons to build this type of submarine.” The main advantages of nuclear submarines over conventional models, the officer explains, are higher speeds, greater ability to remain undetected, and the capacity to stay at sea for longer periods of time. “It can remain submerged on surveillance, defense, and reconnaissance missions for long periods without needing to surface or return to base to refuel,” he says.

Physicist Claudio Geraldo Schön, head of the nuclear engineering course at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (POLI-USP), believes nuclear submarines are an important deterrent. “Because they are so fast and quiet, they can approach other vessels without being noticed,” he says. “For Brazil, with its vast maritime territory, it is important to have a vessel like this to protect our national resources and guarantee our sovereignty at sea,” he explains.

Another goal set by the PNM was to master the technology for producing nuclear fuel. Through collaborations with the Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN), the program achieved early results on this front in the 1980s, when Brazil created its own ultracentrifugation technology, the stage of the process when the uranium undergoes isotope enrichment.

“Only 13 countries know how to enrich uranium. That is the bottleneck of the nuclear fuel cycle,” says nuclear engineer Renato Cotta, a consultant for the PNM and researcher at the Alberto Luiz Coimbra Institute for Graduate Studies and Research in Engineering at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (COPPE-UFRJ) (see interview). “Those that master this technology do not share it with others.” That, he explains, is because anyone able to enrich uranium for power generation is also capable of producing the raw material needed to build atomic bombs.

To understand how uranium is enriched and transformed into nuclear fuel, it is important to know that in nature, the mineral contains only about 0.7% of the isotope U-235 (the ideal isotope for nuclear fission). Isotopes are atoms of the same chemical element but with different atomic masses. The predominant isotope in natural uranium is U-238, accounting for more than 99% of the total. To generate electricity at nuclear power plants, uranium must be composed of at least 5% U-235; for submarine fuel, it must be enriched to 19%.

To achieve the desired level, uranium ore is converted into a gas, which then goes through a cascade of ultracentrifuges operating in series and parallel to concentrate the U-235. The enriched gas is then converted back into a powder, producing the raw material for the pellets used in nuclear fuel. The entire process takes place at various structures at CINA, which employs more than 1,200 people.

“The nuclear fuel cycle is not a secret. You can look up how the process works, the materials required, and the necessary chemical reactions in any book. The difficult part is having the technology to actually do it,” says USP’s Schõn. During Pesquisa FAPESP’s visit to Aramar, reporters were allowed to see the Isotopic Enrichment Laboratory (LEI), where the uranium is enriched, but not the ultracentrifuges.