With one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, Brazil’s prison system has become a cauldron of disease and death. Inmates face a risk of contracting and dying from infectious diseases — especially tuberculosis — two to seven times higher than same-aged people outside. They are also two to six times more likely to die in violent altercations or to — reportedly, at least — take their own lives, particularly if they are young. These heightened risks don’t end with their release. Even after discharge, former inmates continue to face increased risks of disease and death for years before they finally align with those of the general population, with certain unique patterns. For instance, the rate of deaths due to assault and homicide remains exceptionally high after release, unlike in wealthier nations such as Australia, Sweden, or the US, where former inmates are more likely to die from alcohol poisoning or drug overdoses, according to a study published in The Lancet in April.

This grim reality, while not surprising, has been increasingly elucidated in recent years by multiple studies on the lives and deaths of Brazilian inmates, led by a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, psychologists, anthropologists, historians, and sociologists. Much of what we know today stems from studies initiated over the past decade by teams like those of infectious disease experts Julio Croda, of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS) and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), and Jason Andrews, of Stanford University, who have extensively documented the frequency and spread of infectious diseases in Brazilian prisons, along with the causes of inmate deaths both inside and outside these institutions. Further insights have come from studies led by public health physician Ligia Kerr of the Federal University of Ceará (UFC), who started research on the physical and mental health of female inmates in 2014, along with sociologist Maria Cecília de Souza Minayo and psychologist Patricia Constantino of the National Public Health School (ENSP) at FIOCRUZ, who recently conducted a study on the living and health conditions of elderly prisoners in Rio de Janeiro’s penitentiaries.

Their research shows that, much like in other countries, Brazil’s prison system falls short of fulfilling its legal obligations to individuals placed under state custody. Rather than providing suitable facilities for serving sentences, along with access to healthcare and education aimed at “promoting the social reintegration of those convicted and imprisoned,” as mandated by the 1984 Penal Enforcement Act (Law no. 7,210), Brazil’s correctional facilities instead worsen the health of inmates. “While Brazil does not have the death penalty, a prison sentence here can be tantamount to a death sentence,” says Cíntia Rangel Assumpção, a federal penal enforcement officer and the general coordinator of civics and penal alternatives at the National Office for Penal Policy (SENAPPEN), an agency under the Ministry of Justice and Public Security. “This outcome is tied to our societal view that punishment is a form of revenge.”

– Female prisoners have poorer health than the general population and are often abandoned by their families

– Elderly population in Brazilian prisons has increased more than ninefold in 18 years

– Most crimes committed by men over 60 involve sexual assault

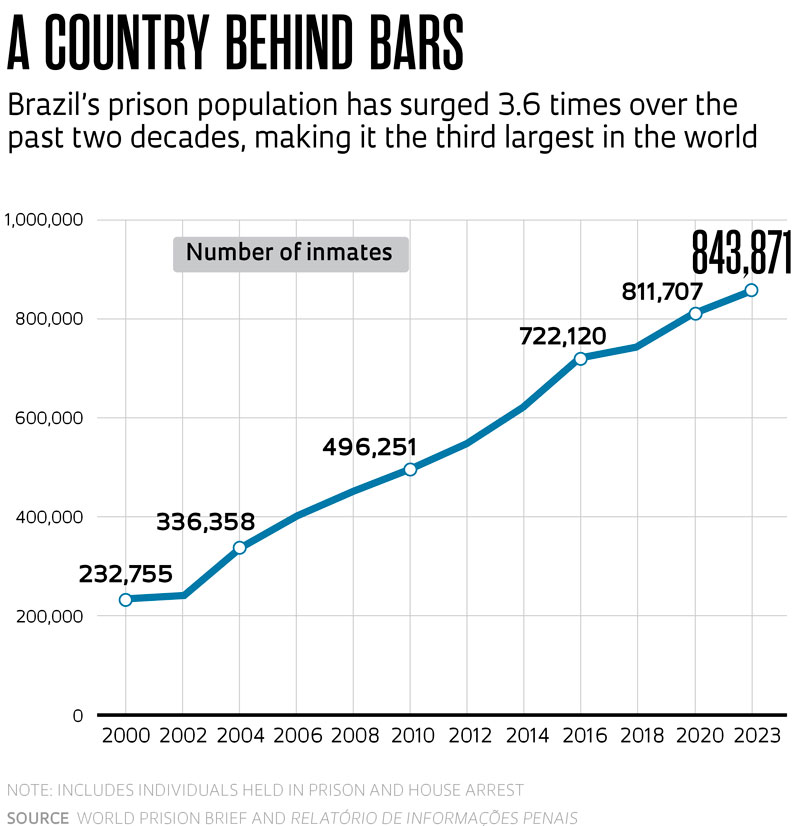

Some experts argue that the prison system intensifies societal problems by concentrating socially marginalized people with limited access to economic, educational, and healthcare resources. According to SISDEPEN, a data collection tool used by the Brazilian Penitentiary System, and the latest “Penal Information Report,” 642,491 men and women were incarcerated in Brazil during the second half of 2023. Of these, nearly 66% were Black or mixed-race; 60% were between 18 and 34 years old; and 59% had not completed primary education. “Generally speaking, these are people without professional skills, who had very few opportunities to enter the job market,” Assumpção notes.

Overcrowded and poorly ventilated cells, poor diets, and limited access to medical care all contribute to making prisons what Croda, Andrews, and epidemiologist Yiran Liu — who has researched the health impacts of incarceration during her doctoral studies at Stanford — described in a February article in the Journal of Infectious Diseases as “institutional amplifiers” of pathogen spread. “Outbreaks of tuberculosis, cholera, measles, mumps, varicella, influenza and SARS-CoV-2 spread with devastating speed through prisons, jails, and immigration detention facilities,” the researchers wrote.

“Prisons are not adequately equipped for healthcare,” says Dr. Drauzio Varella, a pioneer in treating HIV patients within the prison system. Since 1989, he has volunteered to treat inmates in São Paulo’s prisons, and from his experience, he says that little has changed. “The health conditions I encounter today are often the same as 30 years ago in São Paulo’s penitentiaries,” says the physician, who now works at the Chácara Belém Temporary Detention Center in Belenzinho, São Paulo. “Conditions tend to be worse in men’s prisons. Cells often have 5 to 10 more inmates than beds, leaving some to sleep on the floor. In detention centers, there are no on-site medical teams. The state may open positions, but doctors rarely apply. Salaries are low, and the environment is tense.”

Croda and Andrews have conducted seminal research on the prevalence of major infections affecting Brazilian inmates. In the early 2010s, they and their collaborators started systematically tracking serious communicable diseases in prisons in Mato Grosso do Sul, one of the states with the highest incarceration rates in the country — around 650 prisoners per 100,000 people, double the national average (320 per 100,000).

Aline van Langendonck

Aline van Langendonck

The researchers analyzed blood samples collected between March 2013 and March 2014 from 3,600 inmates (85% men and 15% women) in 12 prisons across Mato Grosso do Sul. They found that, on average, 1.6% of inmates had contracted HIV — the virus that causes AIDS, an infection linked to risky behaviors such as unprotected sex, unsafe tattoo practices, or needle sharing — either before or during incarceration. This rate, reported in a 2015 article in PLOS ONE, is roughly four times higher than that of the general population in Brazil. Earlier national studies had identified higher rates, but these were usually limited to a single prison and conducted in the previous decade.

Another virus more prevalent among inmates than the never incarcerated population is hepatitis C (HCV), according to a 2017 study also published in PLOS ONE. Transmitted through contact with infected blood — via shared needles, personal items, surgeries, and blood transfusions — HCV causes silent inflammation in the liver, which can progress to cirrhosis or cancer. In the group monitored by Croda and his team across the 12 prisons, 2.4% had HCV, nearly double the rate found in the general population.

Syphilis was also more common among inmates, according to 2017 data published in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. This sexually transmitted disease, caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, infected 9% of male and 17% of female inmates at some point in their lives, with 2% of men and 9% of women testing positive for the active form of the disease during the study.

The most alarming data pertained to tuberculosis, the deadliest infectious disease worldwide, claiming 1.5 million lives annually. In three rounds of testing conducted between 2017 and 2021, Croda and Andrews’s teams found tuberculosis prevalence rates that, in extreme cases — such as those reported in February this year in Clinical Infectious Diseases — reached 4,034 per 100,000 inmates, or 4%. This figure is 100 times higher than the prevalence of 40 per 100,000 found in the non-incarcerated population.

Throughout their extensive study on tuberculosis (TB), the researchers found that a small proportion of inmates (less than 10%) were already infected with TB upon admission, often asymptomatically. They also observed that after one year of incarceration, one in four people who had never contracted TB tested positive for the bacillus.